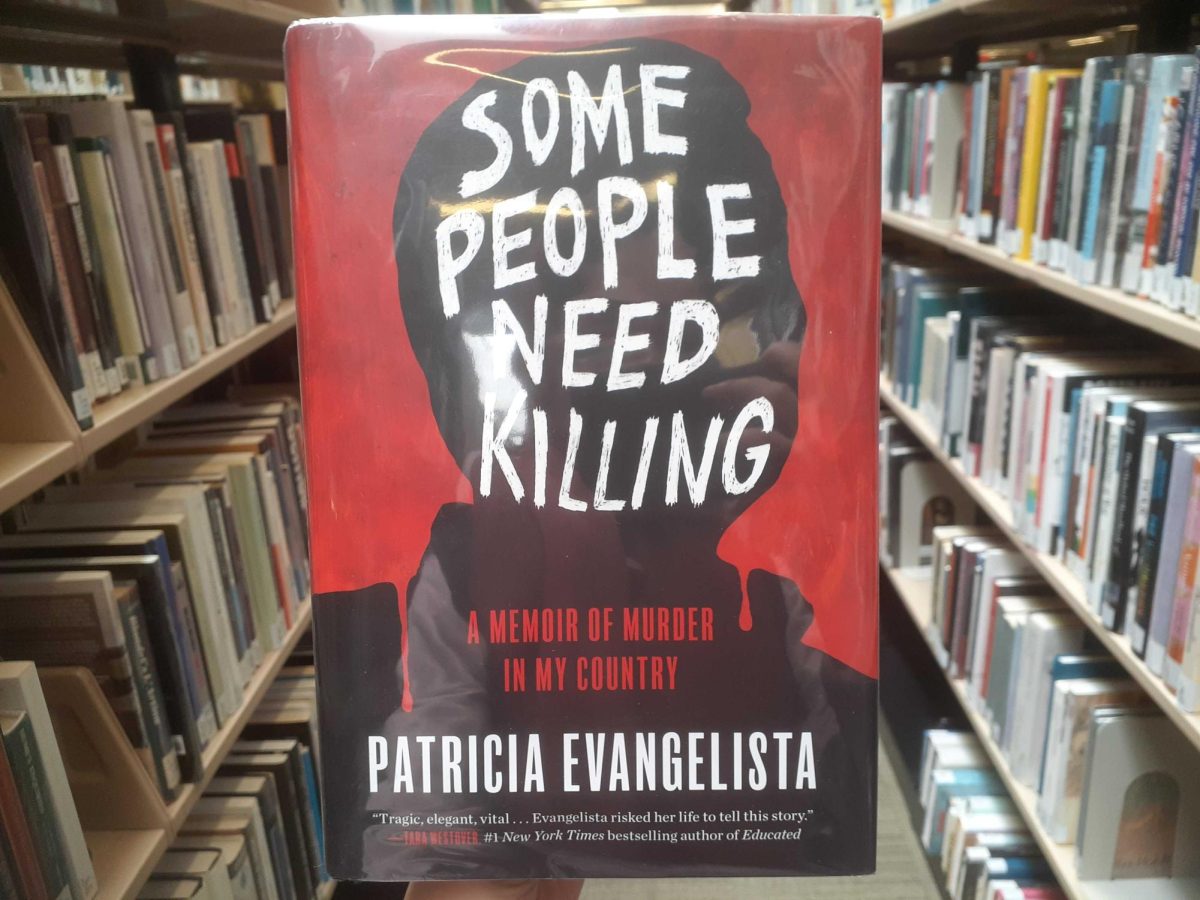

Between the 339 pages of bloody shootings and drug-addicted families in “Some People Need Killing,” there is also a light of hope in the narration presented by the traumatized but brave author, Patricia Evangelista. As a Filipino journalist, she reported on the state-sanctioned killings during the Philippines government’s supposed war on drugs from 2016 to 2022. She eventually fled, fearing for her life as she reported on the government’s crimes.

This book is a standout in the literature of contemporary international affairs, due to Evangelista’s courage to interview hidden sources and research top-secret police affairs. Evangelista’s straightforward narrative and humanizing descriptions make it easy to understand without much political knowledge.

Most importantly, Evangelista does an amazing job humanizing all the people in the book, from young kids who witnessed their drug-dealing parents be killed, to the drug users who survived, to the police chiefs who secretly carried out the violent drug stings.

There was 25-year-old Djastin Lopez who started taking marijuana to deal with his epilepsy, ended up taking crystal meth before for which he was shot ten times by the anti-drug police squads.

There was Efren Morillo, who was shot in his home in an illegal drug raid, alongside four of his friends. Only he survived, bleeding out for seven hours before he was brought to a hospital.

There was five-year-old Danica Mae accidentally shot in her home “with a bullet meant for her grandfather.”

The ones that stuck out most to me were the impoverished families, who often turned to drug deals for money or drug use to help them cope with challenges in life. Rather than addressing the underlying issues these vulnerable people faced, the government demonized them with falsified crime narratives and sanctioned vigilante death squads against them.

It abandoned due process, investigations or trials, opting instead for summary execution in the suspect’s own homes and village streets. Often, evidence and witnesses were falsified by police to make the suspects seem dangerous and justify their shootings. Under the claim of fighting crime, they only led to more violence and societal breakdown.

It’s vital to understand how they got away with this through political manipulation. Evangelista as a writer and journalist understands the weight of words, and she explains the doublespeak used by the Philippines president and police forces to manipulate people into supporting their war on drugs campaign. Studying this book in my World Politics course, it is a good example of the 21st century rise in populist nationalist world leaders.

I found it applicable to the United States’ own “war on drugs” or “tough on crime” era that overwhelmingly impacted impoverished minorities and ultimately led to the nation’s hyper criminalization and mass incarceration that persists today. It helps to better understand the complex situations Evangelista writes about by relating it to the reader’s own knowledge and experience.

As of 2022, at least 20,000 people were murdered according to the ICC, but the Philippines government says only 6,252 were. Evangelista makes the resounding point on pages 310 of the book that the death toll numbers are likely still underestimated and cannot capture the full extent of loss of life and chaos created for FIlipino people.

The language style of the book is really important and adds so much to the reading experience. Evangelista deliberately uses simple language and short sentences to convey the complex events and topics she writes about. Even though as a journalist, she has to remain detached and passive to an extent, it’s clear Evangelista expresses her care for her fellow Filipino people, often the traumatized sources she interviews after the war on drugs shootings.

On page eight, she compares her work to that of a foreign journalist who is more detached from the violence at hand to show the nuance of her work and connection to the people.

“Like Burchett, I am a reporter. Unlike him, I’m not a foreign correspondent. I spent the last decade flying into bombed-out cities, counting body bags and reporting on the disasters, both natural and man-made, that continue to plague my own country,” she writes. “The fact that I’m a Filipino living in the Philippines means that for me, there’s no going home from the field. There is no seven-day shooting schedule, with a pre-booked light and option to extend; only more corpses, every day.”

Therefore, the book becomes not only a lesson about the contemporary political climate of the Philippines and the world but also about the role of a journalist.

This book functions as a nonfiction memoir, but it goes far beyond Evangelista’s life and instead delves deep into the Philippines itself, examining the centuries of history, political turmoil, independence, and modern politics and poverty that shape the issues.

This is a great way for Evangelista to humanize the nation and the issues so it’s not just dismissed as another political corruption government or a drug issue. Rather, she examines all the history of colonization, the Filipino culture and spirit for taking democracy in their own hands, and the ugly truth of poverty and drug addiction that was exploited by the Philippines government for control.

Reading this book for the first time without knowing about the Philippines government or violent “war on crime” will lead many readers heartbroken and confused by the violence. They may want to quit reading because they can’t make sense of the issue. However, Evangelista seeks to mend this by providing a very detailed, well-researched chronological telling of how the political turmoil and violence erupted.

So despite all the horrors in this book, there is a hope created by Evangelista’s bravery as a journalist. Her determination to preserve the stories of the victims she interviews, as well as her dedication to attain justice for the Filipino people against a manipulative government. Despite ending the book on an uncertain note, where Evangelista considers the complicity of the general Filipino public in supporting the regime that inflicted at least 20,000 recorded murders, she also shows us people who care to fix it.