Recently, the Roman Empire trend went viral on TikTok. You may have heard of it, but in case you haven’t, it goes a little something like this; women ask their fathers, brothers or boyfriends how often they think about the Roman Empire and are shocked by the revelation that they think about it often.

Why, these women marvel, would these men think about an ancient civilization so often? What a strange, random thread of thought to occupy themselves with.

And so, the trend evolved into a bigger question; what is your Roman Empire? What is the one subject that can be counted upon to consistently invade your mind and pull your attention away from other thoughts?

Here is my Roman Empire: being assaulted. Being kidnapped, raped and/or killed. Ending up like one of those poor, tragic girls you’ve read about, brutalized and gone.

And I would bet, if you are a woman living in America, it’s probably one of your Roman Empires too.

Like many other young girls, I grew up watching the news that was overwhelmed by stories of violence against women and abductions. Of those who lived one of those nationally broadcasted nightmares, there are few stories more infamous than that of Elizabeth Smart.

In 2002, at the age of 14, Smart was abducted at knife-point from her family home in Salt Lake City in 2002. After nine months of captivity, during which she was repeatedly raped and threatened with murder, she was rescued by the police in Utah.

In the 21 years since her rescue, she has been remarkably productive. She gives approximately 80 talks about her experience and journey afterward every year. She was a commentator for ABC News and is a full-time advocate for the prevention of child abuse who lobbies for legislation and heads a foundation. She is also the author of a New York Times Bestseller, entitled “My Story,” and has recently released a second book.

Moreover, in 2019, Smart launched a self-defense training initiative called Smart Defense to equip individuals with practical tools and skills to protect themselves in challenging situations.

Impressively, Smart Defense program has already gained recognition and acceptance among various educational institutions. Four universities have even incorporated it into their curriculum, underscoring the relevance and importance of such training.

This past Thursday, in the McAninch Arts Center at 7:00 p.m., I was lucky enough to attend “An Evening with Elizabeth Smart” hosted by COD and sponsored by the FT Cares Foundation.

The evening was split into three parts; first, Smart would give a speech to introduce her story and share a message about hope and moving on after tragedy, a dean of students would ask a few prepared questions, and then the floor would be opened up to questions from the audience for the rest of the night.

To a packed audience, Smart smiled and began her talk. Immediately, it is clear that she has given many talks before—she is composed, compelling, and at times, charmingly sheepish.

Meticulously put together, with blonde hair that gleamed under the spotlight, she spoke of loneliness, despair, and hope with a slight Utah accent and wild gestures.

She undercut the seriousness of her subject with bits of exaggerated humor and refreshingly relatable anecdotes. For example, she asked the audience to raise their hand if they had ever used “Stop, Drop and Roll,” training (to which no one did) before mentioning that she used to wish that she’d been trained by a school program as rigorous as the ones on fire safety to put up a fuss if someone tried to make her do something against her will.

Her pointedly nonchalant statement fell like an acoustic blanket on the audience. The sharp quiet echoed.

I thought about the statistics, the estimate that 81% of women and 41% of men, according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, will experience some form of sexual violence in their lives.

I wondered how different so many lives would be if self-defense training was a mandated part of the gym curriculum at my school instead of square dancing or dodgeball. If it was mandatory to teach children of all ages how to protect themselves physically, arming students even in hopes they would never be forced to use what they learned.

Currently, this topic hits especially close to home. As a college student, the issue of sexual assault and learning about how to protect yourself as sexual assault statistics on college campuses in the United States raise significant concerns.

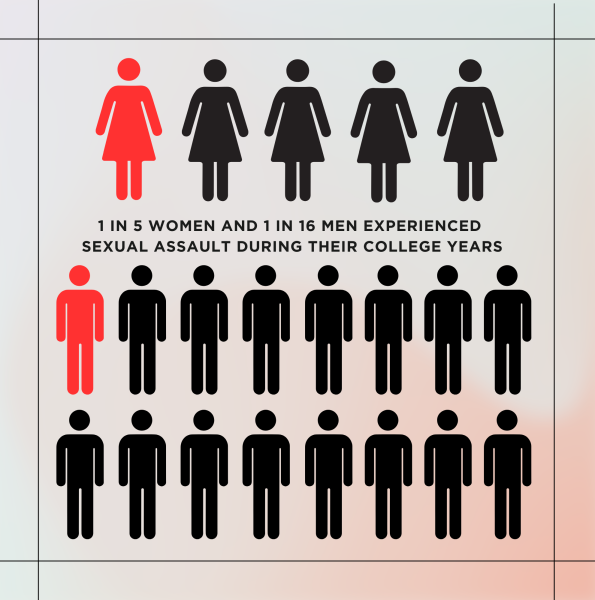

RAINN reports that “1 in 5 women and 1 in 16 men experienced sexual assault during their college years.”

The data also notes a troubling pattern of underreporting where only “20% of female victims and 25% of male victims reported the incidents to law enforcement.”

Reportedly, a significant portion of these assaults were alcohol-related, involving the consumption of alcohol by either the perpetrator or the victim.

In addition, it is recorded that 21% of undergraduate women reported non-consensual sexual contact, highlighting the importance of consent education.

This is an issue that should be at the forefront of our concerns, given that college campuses are meant to be places of education, growth, and safety. Yet, far too often, they become settings for trauma and fear.

One of the most troubling aspects is the prevalence of unreported cases. Many survivors choose to remain silent, either out of fear, shame, or the belief that they won’t be believed. The statistics are alarming, and they only tell part of the story because so many cases go unrecorded.

I sat in my seat, uncertain of how many people in the audience had experienced sexual trauma, but 110% certain it was many more than just the woman on the stage.

She continued with a chilling account of the night of her abduction. Fourteen years old and stolen out of bed, she was held at knifepoint and forced to walk miles through the mountains in the middle of the night before being tied up with steel cables. Smart explained that she spent the subsequent nine months of captivity, bluntly summarizing the truth of her nightmarish situation as and the unimaginable horrors she went through to the audience.

I was particularly struck by the moment she discussed her thought process after the first night she was raped.

Smart has said that, afterward, she “didn’t feel like a whole person anymore.” She felt “dirty” and “broken.” She asked herself, “Who would ever love me?” She even wondered if her family would want her back.

I looked around at the audience and wondered how many of us had felt similarly. Like a piece of gum chewed up and spit out by our experiences. Afraid to speak about certain experiences because we are afraid of not being believed, being shamed, stories dissected and judged if we are not a ‘perfect’ victim.

In that room, as I sat in the dark with stinging eyes and thoughts swarming like flies behind my eyes, Smart spoke to that fear. She is intimately familiar with it, a woman who has borne public scrutiny and questioning since the day she was rescued as a girl and has borne the infinite, heavy label of “Child Kidnapping Survivor” ever since.

And her advice was resolute. She told us, “Never be afraid to speak out. Never be afraid to live your life. Never let your past dictate your future.”

Let me be clear. I walked into this evening as a woman who knows the statistics and knows the unspoken rules to follow to avoid becoming one.

I live my life afraid. I am constantly looking over my shoulder. I overthink smiling at strangers. I don’t make eye contact on the train. At night, I walk streets with the sharp side of my keys poking out of my knuckles and I cross them if a man walks closely behind me.

What I am trying to say is that I am filled with fear and dread and shame and anger so large I choke on it. What I am trying to say is I cannot count on my hands the number of friends I have who have been assaulted.

What I am trying to say is I do not know what I would do if I became a victim. When the first concerns that spring to my mind are about the longevity of a victim label and whether I would have enough proof to be believed, I do not know what my next step would be.

But from the mouth of the survivor of one of the most nationally covered, horrific assault cases of the 21st century, we are told we cannot live our lives in fear. We must move forward, persevering and living life to the fullest. We must speak out, collectively striving for the justice and happiness that survivors deserve.

Her message is a rallying call to action for all of us, imploring us to shatter the silence that still surrounds sexual abuse and to raise our voices. Her unwavering advocacy is a testament to her belief in the collective power of people to protect those who are vulnerable. Her message is clear: together, we can make a difference.

I’ve witnessed the ripple effect of sexual assault on a school campus – the way it erodes trust, creates an atmosphere of fear and leaves survivors struggling to regain their sense of security. It’s not just a personal issue; it’s a societal problem that affects us all. The burden of preventing and addressing sexual assault shouldn’t rest solely on the shoulders of survivors. We need better education, awareness, and support systems in place.

Prevention programs, like the Smart Defense initiative, are crucial for equipping individuals with the skills to protect themselves. Beyond self-defense, there should be comprehensive education on consent, respect, and bystander intervention, ingrained in the campus culture.

We must also work to destigmatize the experiences of survivors and create an environment where they feel safe coming forward. This requires a shift in our attitudes and a commitment to believing survivors.

There’s strength in solidarity and the more we support and empower survivors, the closer we come to creating a campus that’s truly safe for everyone. The fight against sexual assault on college campuses is a collective one, and it’s one that we can’t afford to ignore. It’s not just about statistics and policies; it’s about the well-being and future of countless individuals.

As I sat in the audience, with stiff shoulders and a pounding heart, I was struck by the solidarity I felt. Leaning forward and listening in, there is not a person in that room without a story, without a trauma that set their life on a specific path, without a battle they’ve fought silently.

Around me, a few girls began to cry, muffled sobs gently resounding in the otherwise pin-drop sensitive silence of the room as Smart took a pause. I sat with my lips pressed tight.

Yes, I thought. In this room, we are here together. I was surrounded by women and girls, our shadows kneeling together, our Roman Empires, our complexes blurring and bending. I do not know what you have been through and I could never understand regardless, but here we are together.

Before the Q&A segment, Smart ended her speech by sharing the “best advice” she had ever received.

When she came home, her mother said to her, “Elizabeth, what this man has done is terrible. There aren’t any words that are strong enough to describe how evil he is! He has taken nine months of your life that you will never get back again. But the best punishment you could ever give him is to be happy. To move forward with your life. To do exactly what you want.”

Reader, I do not know who you are or what you have been through. But if you take anything from this article, I hope it is this; refuse to abandon yourself.

Find hope in the darkest moments and believe in the power of your resilience. Our experiences may have shaped us, but they do not define us. Persevere because you deserve to find happiness. Forgive because you deserve to put down the burden of what has happened to you.

Go call a loved one. Go hug a friend. Don’t lose faith in yourself. Don’t lose faith in the world.