The starving artist is a pervasive image in a field where professionals struggle to make livable wages. This issue captures the interest of Minnesota-based artist India Johnson, who has an MFA in Book Arts and Technologies. She mainly works with paper crafts, bookbinding, textiles and has a clothes-mending business.

She shared this expertise with students and librarians at the College of DuPage as part of her Artist in Residence this semester. Johnson encourages artists to take control of their craft, such as by self-publishing, and to uplift each other’s work through a focus on community.

“I’m a working artist who advocates for livable wages and financial transparency in the arts and culture sector, as well as issues like ending application fees,” Johnson said. “The public probably doesn’t realize that museums, galleries and arts nonprofits can get away with spending little to none of their budget on artist pay. Without changes to the status quo, our field will remain inequitable for arts workers, especially emerging artists. I’m not the first or only artist to frame things this way.”

Johnson referred to her Artist Compensation Resource Guide, which provides guidance for new artists to demand fair compensation for their work. The guide also includes essays and studies by organizations that concentrate on the needs of artist workers.

The Chicago Artist Census has an online survey to collect feedback from the city’s artists about challenges they face in a “pay-to-compete” field. This means for artists to get attention for their pieces, they must pay for exposure in museums and art journals, which leads to artists who can’t afford this being side-lined. The study also collects information about how different groups, like people with disabilities, racial minorities and LGBT individuals, may have less access to artistic spaces,

“Besides advocating for arts orgs to devote more than 5 to 10% of their annual budget to artist pay, I’m a proponent of organizing art experiences in the places people already gather,” Johnson explained. “In my artist talk at COD, I discussed working with non-art entities, such as public agencies, libraries and churches, to share my work and fund its exhibition.

This advice benefits artists who live in cities who don’t have large museums and galleries and instead rely on community spaces to display their work. In her Artist Directory, she explains routes for audiences to directly approach the artists next door and hire them for services. Johnson also promotes artist groups in her Minneapolis community such as Queer Threads, which is a craft group for LGBTQ people to meet up, work on projects together and learn from each other.

“In the case of Queer Threads, a rotating group of artists facilitate skill shares,” Johnson said. “In the art world, most of the standard ways to curate a pool of talent involve a competition, i.e. art applications, with poor odds. Instead of forcing artists to compete with their peers, what if we resourced and platformed artists through community groups in which people self-select as artists?”

Johnson facilitates non-competitive artist meetings, that provide a unique opportunity for young, diverse artists to work at a professional level. Queer Threads will have its first members’ exhibition this winter.

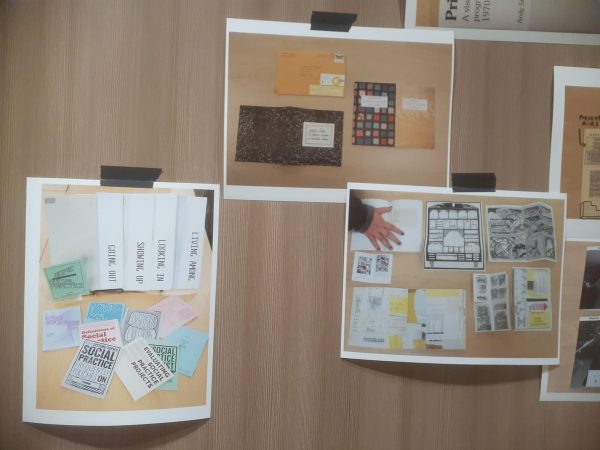

Another community resource that Johnson provides is Open Copy, a self-publishing studio in Johnson’s home, where she provides photocopiers and other equipment to local artists who need to scan and copy their paper-based artwork like zines. Open Copy is an affordable walk-in service, at only five to 20 cents per page. Zines are paper compositions with text and images that are arranged in a collage and often communicate a theme.

By teaching artists how to create their own books and zines through self-publishing, India hopes to give them more agency, so they don’t need to rely on expensive institutions to display their artwork. During her Artist in Residence work, Johnson taught a crash course on self-publishing to photography students. She also taught Library Technical Assistants to create homemade books.

In the book-making workshop, librarians created 8-page books out of 11 by 17-inch papers. They used many special tools, such as a bone folder, which is a plastic stick with a pointed edge that’s used to make foldable creases. They also used rulers and straight knives to cut the paper into pages. By the end of the residency, Johnson said she will have taught at least 50 people at COD to make their first book.

Erin Fairhead, who is a reference desk librarian, discussed how Johnson guided them through the workshop.

“Although I work with books almost every day, I’ve never constructed a book, and this was my first time working with a bone folder,” Fairhead said. “India gave us tips on how to work with our materials. She told us that paper is not always cut perfectly, so our folds might not be exact. She taught us a technique for how to hold the straight knife at an angle while cutting our paper, and how to hold and move the ruler we used to guide our cut.”

The librarians were able to stylize their homemade booklets with writing and printed graphics. Librarian Laura Burt-Nicholas described how her book uniquely incorporated pockets, like a folder.

“Each page of the book contained a small pocket where something, a small polaroid, a keepsake, some other tangible item, could be stored,” Burt-Nicholas described. “I haven’t put anything in my book yet, as I’m still thinking about what I’d like to collect together—should it be the same type of item or items linked by a theme? I don’t know!”

The librarians also discussed how the workshop changed their perspective on the traditional systems used in libraries, especially with the organization of books.

“Seeing the different zines [India Johnson] had collected showed how amazingly creative and thoughtful our work can be,” Burt-Nicholas reflected. “One of the books, for example, was the work of a cataloger, someone who describes books in the library catalog. After his retirement, he focused on requesting changes to cataloging language so that it would be more inclusive of all library users and often so that it would be more conversational and the book recorded that work. The book was unique, interesting and gave me a strong sense of his personality.”

Johnson also introduced the librarians to the book “Unpacking My Library” by Buzz Spector. This book is on display in the COD Library as a companion piece to Johnson’s book-making workshop. Spector is a contemporary visual artist who arranges the books in his personal library by size, rather than alphabetically or by genre.

“This made me think about how I view books in the library as information that needs to be organized in a certain way to be found,” Fairhead said. “After viewing Spector’s work and listening to India’s discussion, this made me wonder about how viewing books as objects would impact my view of the library, and how I might arrange books if I choose to organize them by size, color, or any other attribute.”

By experimenting with the common perceptions of books, Johnson’s workshop encouraged the librarians to consider other collections that libraries offer, like film DVDs, magazines or board games. Even the metal welding sculptures displayed on the second floor of the COD Library carry this concept.

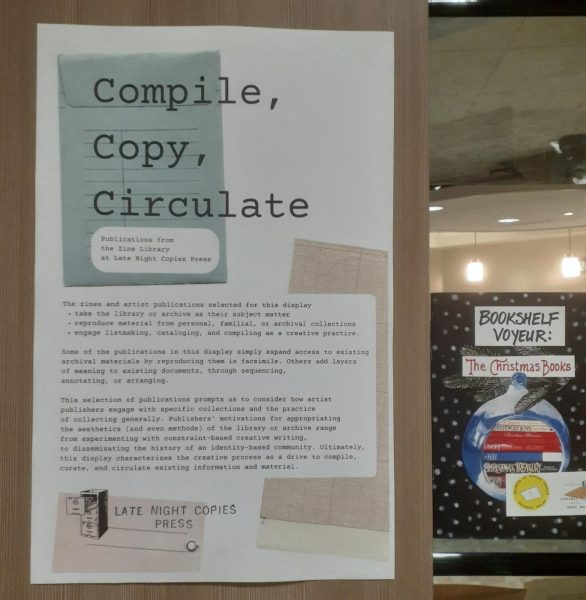

Photos of Johnson’s zine collection were displayed on the first floor of the COD Library. The zines are composed of drawings, vintage posters and text that convey themes of social solidarity.

The overall themes explored in Johnson’s workshop were to examine books and non-books, as described in the promotional poster for her Artist Talk.

“By books and non-books, I mean that everything I do as an artist exists in relationship to training in bookbinding and book repair,” Johnson said. “Sure, not everything I currently make is a book, but this training cultivated my interest in tactile art that is supposed to be handled and in work that is participatory or interactive. Some of the pieces I consider non-books, for example, happen in or are about libraries, or explore connections between books and other media, like textiles.

Whether through textiles, zines or bookbinding, Johnson’s work promotes self-resourceful artists and a society that values the artist’s creativity over the price tag.