Stan Mikita was endowed my grandfather’s flamboyant “puke-coloured” trousers

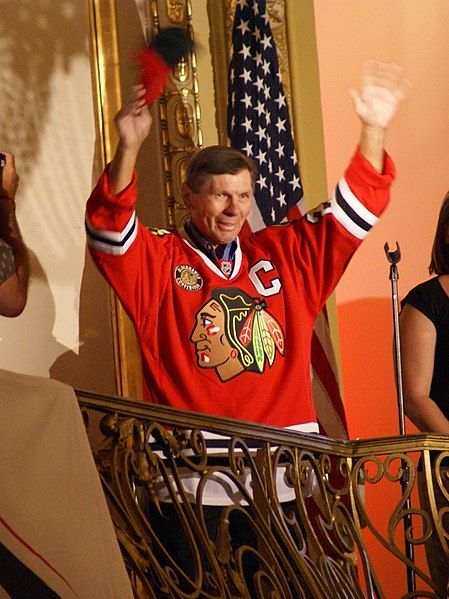

Stan Mikita

April 20, 2018

Stan Mikita was endowed my grandfather’s flamboyant “puke-coloured” trousers.

An avid golfer, hockey legend Mikita was once a high-profile member at Medinah Country Club coinciding with my grandfather Gene Wietecha’s tenure as the club’s register. It was Mikita’s birthday, and the club was organizing a celebration. The caddymaster asked the staff if anyone had anything flamboyant enough to fit the idiosyncratic and rather peculiar taste of the hockey legend’s fashion.

Wietecha explained, “I had a flamboyant pair of golf slacks I called my “puke pants.” They looked like somebody threw up on you and you tried to wipe it off with a towel. There were some browns and yellows and a little orange plaid. Stan had a pension for striking attire, and I had outgrown them, so I knew they were perfect for his outlandish style.”

Mikita, a straight-and-narrow humble man would often contrastingly wear these gharrish clothing choices out in public, even riding his lawn mower on his front lawn in Burr Ridge wearing flamboyant patterned pants or shorts.

Wietecha described Mikita as a delightful and humourous member, often pranking him and the club members.

I asked if Mikita died tomorrow, what would you most remember about him. And replying with a sincere gratitude in his eye, “Even though he was a massive star, he always treated me like a normal equal person,” Wietecha said.

Mikita seemed to always provide memories such as these with everyone who had the privilege of living in his presence. Whether personal memories or those recollecting the grandeur of magnificent moments in Chicago sports history, memories of Mikita burn on in the minds of everyone his light touched.

However, in Mikita’s own mind, the lights suddenly began to grow dim, one by one, and now tragically have succumbed to darkness. Mikita, 77 years old, suffers from the devastating progressive neural disease of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB).

Lewy bodies occur when abnormal clumps of a neural protein called alpha-synuclein clog and impair neurons in the brain. This impaired function of the neurons leads to progressive dementia and cognitive difficulties. It also causes hallucinations, further impairing the mind, and abnormalities during REM sleep, exacerbating the conditions of the disease and perhaps leading to the formation of more Lewy bodies. Currently, there is no cure, and medication will not subdue the progression of the disease. Current treatments only aim to alleviate some of the symptoms, but often lead to a devastating worsening of the other symptoms.

Mikita’s family announced in 2015 that he was diagnosed with the disease, now rendering him completely devoid of all the beloved memories of his former life. Sudden, swift and brutal, the disease has left him essentially absent from the head up.

For Mikita, the tragedy began suddenly. He once got lost driving home from Medinah Country Club, a drive he had taken countless times before. Then, the memories he built his spectacular career around, all went out, one by one.

On April 6th, the Chicago Blackhawks honoured Mikita’s legacy as part of their “One More Shift” initiative. Three of his grandson’s donned his famous No. 21 jersey, skating around the United Center to a thunderous standing ovation from the most attended game of the season.

All stood in reverence of what the legend gave to us.

If you can no longer recall, Stan, here are the glorious memories you are missing.

Mikita moved to Ontario at the age of eight to escape communist-controlled Czechoslovakia, quickly falling in love with the sport that would become his life.

During his sophomore season with the Chicago Black Hawks (two words at the time), Mikita helped the Black Hawks triumph over their arch-rival Detroit Red Wings to win the 1961 Stanley Cup, their first since 1938, and their last championship until centre Jonathan Toews, emulating Mikita’s leadership, helped the Hawks win the 2010 Stanley Cup. Mikita’s league-leading six playoff goals signaled the brilliant career that was to come.

Mikita matured to become the greatest and most feared centre of the 60’s. Alongside the formidable Golden Jet, Bobby Hull, Mikita helped turn the Black Hawk’s offense into the most dominant force of the physical decade.

- His entire career was devoted to Chicago (1958-80)

- All-time team leader in Games Played (1,396), Assists (926), Points (1,467)

- Second to Bobby Hull in Goals (541)

- He led the league in scoring four times (1964, 65, 67, 68)

- In 1966-67, he tied the league’s all-time total season point mark, tying Bobby Hull’s previous record of 97 points (currently held by Wayne Gretzky at 215)

Mikita’s magnificent career culminated in him currently being 14th all-time in regular season points.

His feisty nature turned him into a cunning defensive forward, however, it was the agility in his stickwork and his skating finesse that drove fear into his opponents.

As my Grandfather recalled of Mikita and Hull’s chemistry, “I attended one playoff game where the Hawks were playing the New York Rangers. They were tied going into overtime. On a face-off, Mikita with lightning fast speed finessed the opposing centre, throwing him off balance, and slipped the puck through his legs to Bobby Hull. Hull wound up and sent a zipper past the goalie, and just in a flash the Hawks had won.”

“Mikita was a fearful pugilist when he came into the league,” Wietecha continued. “He fought everyone, never caring he got beat most the time. He had some of the most penalty minutes in the league, and then all of a sudden he went to winning the Lady Byng Trophy with the fewest penalty minutes and for exemplifying great sportsmanship.”

Mikita supposedly evolved his goonish behaviour after his five year-old daughter remarked while watching a game, “Mommy why does daddy spend so much time sitting down?”

The always intrepid innovator, after using a broken stick blade that got curved after jamming into a door, Mikita saw the dynamic potential behind using such an apparatus. He was soon using a propane torch to craft deliberately curved sticks, giving greater power and lift to his shots and more skill to puck-handling. This helped turn him and Hull into an unstoppable goal-scoring machine.

After an errant slap-shot tore off a piece of one of his ears (it was stitched back on), Mikita designed and continually used a hockey helmet for the rest of his career.

Mikita preached the helmet was a way to protect one’s self from the brutal physicality of the game. However, the damage had already been done. Mikita intends to donate his post-death brain for scientific research regarding chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) caused by excessive concussions and brutal hits amassed during his lengthy playing career.

Correlation between possible CTE and his dementia will have to wait to be proved.

Mikita was always giving, whether founding a hockey league for hearing impaired athletes, or advocating for and volunteering in the Special Olympics hosted by Chicago.

In 2011, the city responded to a life of giving, by erecting a bronze statue of Mikita with a “C” for captain forever standing sentinel in-front of the United Center with other irreplaceable Chicago athletic luminaries such as Bulls superstar Michael Jordan.

Mikita still maintains peak physical fitness, but from the head up he has left us. It is devastating for family members and those who love him, seeing the man stripped of his glorious life and suffering from the onslaught of his symptoms.

I remember the sheer aura and gravity of his presence as Mikita and Denis Savard presided over one of my Blackhawk Youth Training Camps at the Edge in Bensenville. I think of all the memories that in the end will comprise my life, and I hope the memory of Mikita is one light that will never go out.