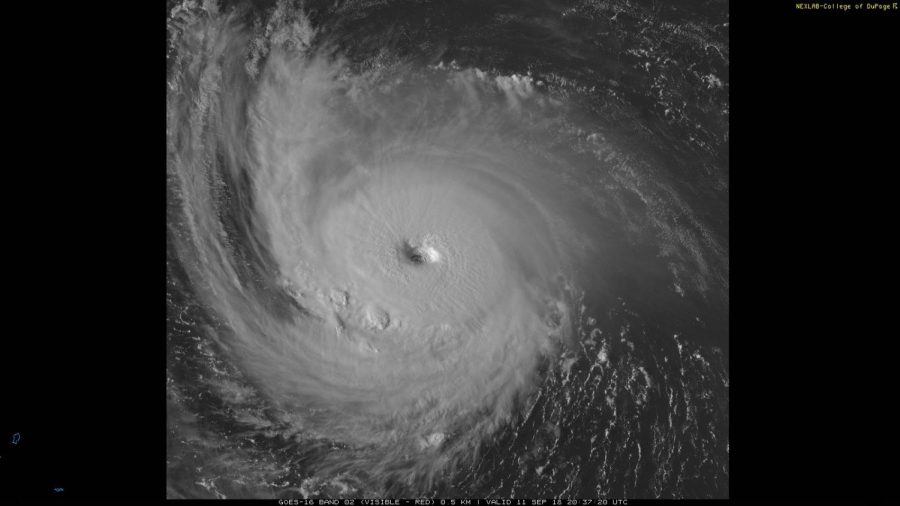

We Didn’t Start The Fire… Or Did We?; Are Humans Making It More Likely for Greater Intensity in Severe Weather Events Like Hurricane Florence?

September 25, 2018

The destruction caused by Hurricane Florence on the east coast renewed debate about climate change and the role humans play in it. While the scientific community generally agrees human activity is making it more likely for greater intensity in severe weather events, Ronald Stenz, an assistant professor of Meteorology at College of Dupage, fears oversimplifying the human role in climate change has become the most dangerous precedent of all.

Although the majority of the scientific community agrees we are increasing the likelihood for greater intensity in severe weather events, to say we are causing them is much too nearsighted to understand the vital intricacies of the question, Stenz said.

“Education would be a big thing instead of oversimplifying a problem which can leave out a lot of the understanding of details that is needed,” he said. “Florence, as an example of climate change, the evidence to support that is very limited. You would need to do an in-depth study to see what exactly happened with Florence and if there was anything in particular there that is made more likely in a climate change scenario.”

It is well agreed upon within the scientific community that there is a trend toward an increased average global temperature based on our temperature record utilizing satellite measurements. Along with this statistic is the influx of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. This is particularly true with Carbon Dioxide or CO2. CO2 functions as a greenhouse gas by absorbing the longwave radiation from the earth and reemitting it into space. This results in a warmer atmosphere and a warmer overall global climate.

There is some division as to how much of the warming is caused by CO2 in the atmosphere from human contributions. Regardless, when there is a warmer overall climate and warmer oceans, it is possible for hurricanes to have more energy to develop and sustain themselves and to, therefore, be more powerful. Despite this, we cannot with confidence say that climate change is causing these events or making them more dramatic, Stenz said. Weather and climate are both separate, intricate, and deeply complex subjects that both depend on a large variety of factors. Even more complex is the relationship between the two of them. Although we can reasonably say there is climate change towards a warmer average global temperature, and that should make hurricanes either more likely or more intense, neither has been the case.

There has been no significant trend toward more frequent landfalls for hurricanes originating in the Atlantic since the 1880’s. There is no definitive trend showing more intense hurricanes. In regards to climate’s relationship to weather, we can only say certain weather events might be more likely based on the climate and its changes, Stenz said.

There are always unforeseen or contradictory factors to take into consideration. When we have climate change or global warming we’re changing patterns of circulation around the globe, and there’s large uncertainty in how things will actually play out once that happens.

Nonetheless, the potential impacts of extreme weather events cannot be ignored. Stenz has reviewed the data on climate change and considered its potential implications.

“With a climate change scenario, if you increase the temperature of the planet 2 degrees Celsius, you would maybe make it possible for a hurricane to produce more rainfall,” Stenz said. “That percentage from recent research I’ve seen estimated is possibly 10 percent more rainfall from a hurricane or tropical system if you have a warmer planet.”

A warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapor. More water vapor could increase the probability of higher rainfall rates.

The misconception that there are a greater number of storms and storms of greater intensity could be attributed to the progression of our technology. In years long past, extreme weather events might have occurred where no one was around to see them, or if they were, they may not have been communicated to everyone effectively or pertinently. The presence of advanced detection technology today, as well as social media, has been a marked shift in public awareness of extreme weather. When there is an extreme weather event, everyone knows about it. To Stenz, this increased exposure to the knowledge of extreme weather has contributed to the perception that extreme weather is more common even though that is not the case.

With such a non definitive link between climate change and individual severe weather events, Stenz said the focus on potential consequences should be shifted onto more pressing associated dilemmas.

“Some of the biggest killers and disruptors to lives and property are things less talked about like heat waves. If heatwaves are more likely, those have pretty severe consequences sometimes. Especially with elderly populations or people more susceptible to that. We do not talk about it much, and that is probably where it becomes dangerous, you can have many lives lost due to that. In a warming climate, you would probably expect your heatwaves to be worse if you are shifting up your mean. Then there is the impact on power grid when everyone is running their air conditioners. There is really lots of facets in how weather can impact people.”

However, Stenz said the most pressing dilemma is the danger of the continued oversimplified public perception of the connection between weather events and climate change. This becomes most dangerous in the case of research and conversation on the subject. If people think every time a violent storm occurs it’s due to climate change, it can make it impossible to come to a collaborative and intelligible understanding of the issue of climate and how to solve it, Stenz said. There have been destructive storms in the past, and they haven’t been necessarily associated with climate change. If those storms were to happen now though, that’s all that would be talked about, Stenz said. When politics and science become intertwined with one another, the scientific knowledge that needs to be conveyed to the public is often times misconstrued as a means of being able to forward political agendas. This has a powerful overall influence on the public, Stenz said, and distracts from the issue and the attention that it really requires.

Stenz has ideas as to how the scientific community can bridge this gap of understanding to the public over time,

“Trying to convey the difference between weather and climate is really important,” he said. “One weather event does not mean climate change is real or isn’t real. One season does not even mean that. Climate is average conditions over a long period of time. Within that, you are going to get some variation. Finally, relating impacts to people’s lives is a good one for why they should care about it. Coastal areas is where I would put my biggest focus, where, something like sea level rise is dangerous. Then trying to convey that things are probabilistic. It is not one thing happens, then everything bad will happen because of it. It is increasing probabilities.”

This heightened awareness, as well as a more objective view of what is being most concretely communicated by the data, establishes the foundations for the stage on which the climate change mitigation and adaptation conversation can be had, Stenz said.

“Just because someone is skeptical about your idea doesn’t mean they think everything you say is wrong,” he said. “If someone is asking you questions, try to answer them. Maybe question your own viewpoint as to why you believe in something. That is how science works. You have an idea. You should be able to defend it with reasoning, facts, data and evidence to support your argument. I think that is what is missing now.

“Some people will refuse to believe any evidence you provide them, but there are people who are asking legitimate questions where there is uncertainty,” Stenz continued. “If those legitimate questions get shot down right away, that is not healthy. When the time comes to mitigate and adapt, there will be no way to get those two groups to talk to each other on whether or not climate change is real, or what we have to do about it.”