My Favorite Podcast: “My Favorite Murder”. Reasons for becoming a Murderino, like me and many others

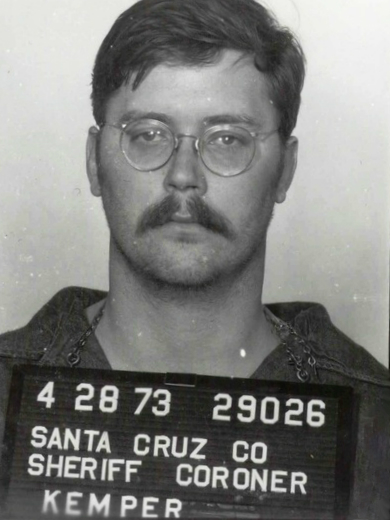

Edmund Kemper, Serial Killer

May 20, 2018

I am not the only one. I certainly never thought was weird or that my hobby should remain a secret, but I would never have imagined I was part of a group so large that it consistently fills auditoriums and concert halls across the world. I am a Murderino, and you can be one, too.

The term Murderino refers to a person who is obsessed with mysterious deaths, serial killers and all things murder. It was coined by a fan of the now infamous podcast “My Favorite Murder,” created by Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark. The fans of the podcast quickly adopted the name, and soon it was official.

“My Favorite Murder” is not my first soiree in the world of true-crime “entertainment,” but it has become the most addictive. Not only does it satisfy my fascination with murder and mysteries, but it also is a daily therapy session and a way to guarantee everyday will both begin and end with a smile.

Frequently the top comedy podcast on the ITunes chart, Karen and Georgia somehow managed to create something magical by combining their comedy and TV backgrounds with their own love of murder stories. Certainly those elements have drawn people in, but the podcast provides so much more to the listeners. It is a place where people go to get advice, support and a source of comfort and exposure therapy. Here are four things about “My Favorite Murder” the podcast, and its hosts, you might not know.

The podcast is about confronting our fears

The podcast may sound like it is created by and designed for those who take murder or death lightly, but in reality it is about exposing ourselves to the things we fear the most. In an interview with the Washington Post, Jason Smith, who runs the podcasting network Feral Audio that supports “My Favorite Murder,” said the audience is 80-85 percent women. Georgia Hardstark, one of the hosts, said her fascination with murder is grounded in her own fear of it happening to her.

In an interview with the Atlantic, Hardstark said, “You have to confront your fear to prove that it can’t actually hurt you.”

There are times the podcast gets incredibly emotional, and there are times when it can be empowering. For all the stories about tragic death, there are also stories of survival. One story in particular, about a woman named Mary Vincent who survived a vicious attack that left her a double amputee, sticks out for many of the fans, as well as the hosts. These stories remind us it is not just about death, but about the appreciation for life and the celebration of survival.

The podcast teaches us how to be safe

While regaling its audience with macabre stories about the worst serial killers in history, such as Richard Ramirez and Edmund Kemper, the hosts also take the time to make sure we learn how to protect ourselves. The program encourages listeners to be the first people to call the police when we see something, or to ask women who seem lost, scared or uncomfortable if they need help, or to simply say “F*#k politeness.” This particular catch phrase, which is now plastered all over “My Favorite Murder” merchandise, is a reminder that nobody owes anyone their time or their courtesy. Kilgariff and Hardstark point out that adults should never ask children to help them find their dog, and that a grown man should never ask a woman he doesn’t know for help. Advice like this may seem counter to the sense many women have to be gracious and helpful, but the hosts remind us Ted Bundy killed women by first luring them away from a safe public area by asking for help.

As a helpful person, advice like this stood out. Being aware of my surroundings, noticing strangers who make me uncomfortable, noticing children who may not be with their parents and keeping an eye on them, walking in well-lit and populated areas and putting my safety above my public image is becoming second nature. For many listeners this is true.

The podcast focuses on respecting victims and the vulnerable

Kilgariff and Hardstark admit they are still learning with us, and that they are neither investigative journalists, nor professionals in this area. As episodes progress, they focus on connecting with their audience and learning from them. This is especially true of audience members who work with crime, psychology or victims of violence. They discuss the power that inaccurate language has when discussing these serious topics. No longer using the word prostitute, they prefer the term “sex worker” to describe the individuals who work in this high-risk industry. It is a reminder that all individuals, and all victims of crime, are equally deserving of being remembered respectfully. Rather than simply sympathizing with those who lost their lives, the hosts try to celebrate their lives and discuss the ways they fought back.

They also have a corrections corner where they address any mistakes in previous episodes or even mispronunciation. Another major correction has been in relation to the overuse and misuse of the terms “Psychopath” and “Sociopath.” While they acknowledge they will never get everything right, they make sure they are doing their best to be honest and upfront about what they don’t know, encouraging the audience to do the same.

The podcast encourages mental health care

One phenomenal aspect of the podcast for many of the listeners is the honesty of the hosts, who are completely open about their own struggles with addiction, anxiety and their mental health. Kilgariff frequently discusses her years-long struggle with alcoholism, and Hardstark talks about her visits to her therapist. In one episode, they opened by talking about a therapy appointment they had together, in order to work through some miscommunication issues. Therapy is not presented as a last resort but rather as a part of how we should take care of ourselves.

Self-love is a large theme, and topics including body shaming, eating disorders, self and relationship abuse, and anxiety are explored. To a largely female audience, who frequently deal with similar insecurities, this is therapeutic. The Atlantic reported about one fan, Windy Maitreme, who was inspired by the podcast to make her first therapy appointment.

“‘I couldn’t believe how much they talked about mental health issues and how they were very open about seeking therapy,’” Maitreme told the Atlantic.

In an email to the Atlantic, Hardstark commented on this aspect of what they do.

“We’re both oversharers. So opening up happened naturally for us …. Luckily people liked it, because now we don’t have to pretend to be perfect or experts or anything we’re not.”

“My Favorite Murder” can be found on the Apple podcast application, iTunes, Spotify, Stitcher and Feralaudio.com. Find out more on their Facebook page at www.facebook.com/MFMpodcast/