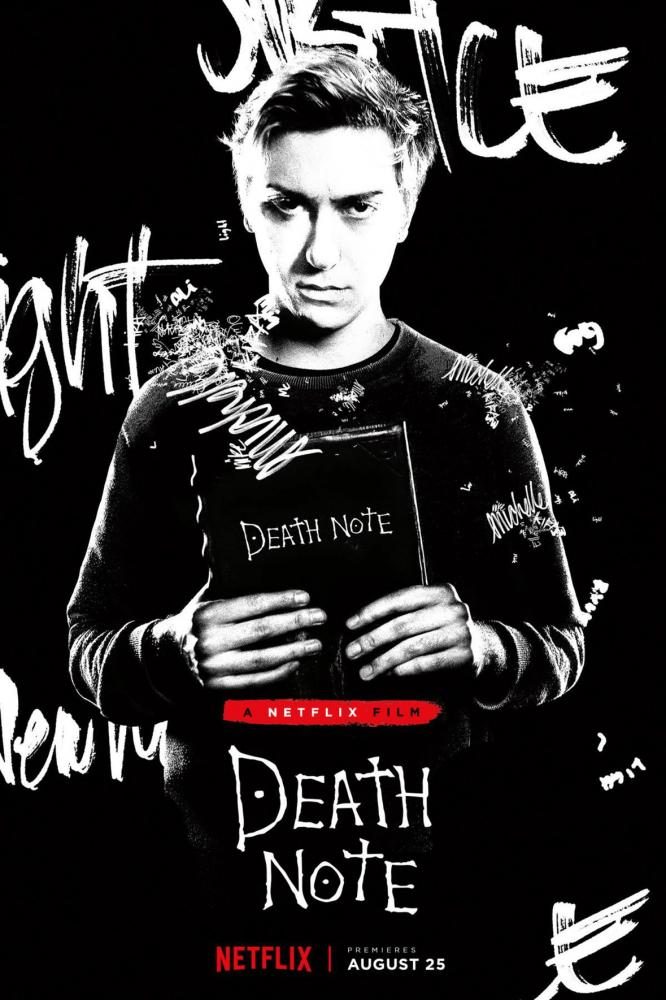

Netflix’s Death Note: Yet another hollow adaptation of a Japanese classic

August 30, 2017

Death Note’s premise is simple: it’s basically a notebook from a death god, or Shinigami, that gives whoever wields it the power to kill anyone they please as long as they’ve seen their victim’s face and known their real name. The kicker to this unholy amount of power? The owner gets to choose how the victim dies, no matter how gory it could be, as long as it’s in the realm of possibility. And that realm of possibility blew my teenage mind, still in high school, barely 17 years old. I could still remember the days of bingeing the whole anime in a span of a school week, pulling an all-nighter to watch the two Japanese live action films…leading up to when I have finally saved up enough money to buy an exact same replica of the notebook. Even though I knew it was fake, having it in the palm of my hands felt like I had been given a tremendous responsibility.

Imagine my surprise and immediate skepticism when Netflix announced they were doing a live action Death Note film. Cue in the drawn-out list of disappointment from westernizing successful Asian films and TV shows for the past few years: the most recent Ghost in the Shell and the whitewashing controversy it came with, the half-assed remake of the South Korean film Old Boy, that god-awful Dragonball Evolution movie….the list goes on. That’s why I had a small glimmer of hope when I found out Adam Wingard would be directing it, the man behind some of my favorite independent horror flicks like You’re Next and The Guest. Wingard was given the daunting task of compressing 37 full episodes of the source material into less than two hours, and that is without taking into account the extra details from the manga comics.

Like the original, Death Note follows Light Turner (Nat Wolff), a brilliant but introverted high school student who accidentally finds a mysterious notebook that grants him the power to mete out justice as he sees fit. Light then meets the notebook’s keeper, the death god named Ryuk (Willem Dafoe), in possibly one of the most embarrassing scenes in any movie I have ever seen. As Ryuk manifests for the first time, he manages to scare the living hell out of Light, prompting him to run and scream like a literal man-baby scared of out of his wits. Ryuk introduces Light to the book’s many rules and coaxes him to use it.

The entirety of the movie can be summed up by the film’s first 10 minutes, as Light eventually gives in to Ryuk and picks his first target. Hesitant at first, he writes the name down. The victim dies from a grisly but very satisfying decapitation a few moments later, triggered by a twisted series of domino effects, reminiscent of the Final Destination films. This rapid and unnecessarily gruesome montage is Death Note in a nutshell, and the rest is mostly just cannon fodder. Chaos ensues as Light goes on a killing spree, inventing the persona of ‘Kira’ and basically calls himself a god of justice claiming credit for the killings. Kira’s body count eventually attracts the attention of law enforcement, and the eccentric detective aliased “L” (Lakeith Stanfield) who’s hell-bent on doing whatever it takes to stop the mass murder, turning the film into a cat-and-mouse game.

It’s hard not to compare the quality and character development of the original with the remake. Nat Wolff’s performance as Light is a complete miss. Light in the remake falls oddly between an unhinged sadist and a whiny teenager, not fully decided on what his motivations really are. The movie solves this problem by giving him a half-baked back story, recounting how his mother was murdered by a criminal who’s still at large. This fuels his very vague sense of justice and fills him with the desire to kill the “bad guys”– but these topics weren’t fully explored on any significant level. Light manages to avenge his mother’s death not even halfway through the movie, with little to no catharsis for the character’s development. Wolff’s portrayal comes off as another troubled teen with raging hormones who can not make his mind up as his character speaks with a nonchalant, almost constipated look that doesn’t fit someone who’s contemplating the complexities of life, death, and murder.

Everyone seems to lack any basic motivation, as seen from Light’s father, James Turner (Shea Whigham) who heads the Seattle investigation behind Kira’s killings, to Light’s accomplice girlfriend, Mia (Margaret Qualley). Mia’s character never really offers anything but a slight nudge to Light’s already questionable morality. Her shallow character never really learns anything. Her sudden desire to aide Light with murdering people is completely perplexing, and at best, her character seems to be like another bored teenager with some unresolved anger issues.

The plot heavily suffers from the addition of the angsty, coming-of-age teen romance between Light and Mia, making the story more convoluted. The film tries its hardest to make their love central to the plot, and yet they fight and whine relentlessly throughout the film, offering no real romantic chemistry. Some might argue that the original had a romance between these two characters, too, but what the remake fails to capture is how straight-up psychopath Light becomes once he started killing off people, and how he treated everyone as chess pieces with little regard to their lives. In its original form, it was clear from the get-go that he was only using Mia’s character (Misa in the original manga comic) as a pawn to further his agenda.

And that’s what made the original highly entertaining: seeing Light, a charismatic and popular student, discover his dark side, akin to Breaking Bad’s Walter White. Light uses this charm to fuel the strength of his villainy; he never once regretted nor questioned his motives as he got engulfed in the delusion of becoming mankind’s savior by ridding the world of criminals and bad people. He becomes consumed by the power of the notebook, using those closest to him to get what he wants. His eventual downfall felt more tragic as it didn’t just affect him, but everyone who knew and loved him. Netflix’s Death Note failed to capture this essence. The storyline is alienated by the film’s decision of making Nat Wolff’s version of the character into your run of the mill, average loner.

This almost hollowed out adaptation gets to the core problem of Netflix’s Death Note. Wingard’s reimagining of the classic Japanese series is too simplified and disappointing. Death Note, in its original form, is a game of wits between Light and L and that’s what made it compelling to watch. Seeing Light constantly push the notebook’s rules and limitations is a spectacle to be seen. There’s this one particular scene from the anime where Light manages to kill off people by using a bag of potato chips as a disguise from surveillance, and it is one of the most absurd but brilliant scenarios I have ever seen on TV. Light’s clever evasion of rules without getting caught as L tries to wade his way through a game where he can’t see the field makes the original a highly entertaining watch with each episode. This conflict allowed Light and L to develop a dynamic relationship between them out of grudging respect for they recognized each other as worthy adversaries. The remake never left room for these two to develop the same rapport. Instead, L’s character hardly posed any threat to Light. This made every encounter between them an anticlimactic dead space. The two characters had no real tension and even the chase scene at the end didn’t offer any payoffs.

Although Willem Dafoe portrays the death god Ryuk with pitch-perfect mania, the character is left with little sense of importance at all, too. Their decision of making Ryuk more malicious and complicit was a great idea but there weren’t just enough of his presence to make him important to the story, except maybe as a spectacle for special effect.

The verdict? I’d go back in time and write this remake in my Death Note to stop it from ever hitting the screens.