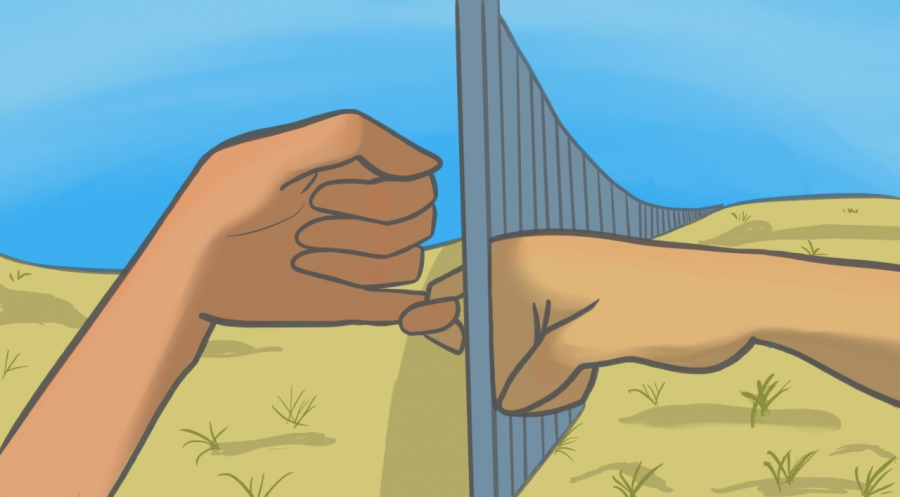

Love separated by borders

(Beyond Borders: Undocumented Mexican-Americans)

The documentary “Beyond Borders: Undocumented Mexican-Americans” shown at the College of DuPage as part of Hispanic Heritage Month, features the tragic stories of those torn apart from loved ones due to immigration policy (graphic by Jessica Tapia)

October 10, 2019

Whispering “Te amo” and blowing kisses through narrow slits of steel on the Mexican-American border wall, deported immigrant Yolanda Verona extends her pinky through the wire to embrace her children confined on the other side.

Verona and her children’s “pinky kiss” is featured in the documentary “Beyond Borders: Undocumented Mexican-Americans” shown by the College of DuPage’s Living Leadership Program. The film was shown as part of the school’s Hispanic Heritage Month festivities.

“It feels as if I’m in a cage like an animal,” said Verona in the film. Her agony is blended with the harrowing tales undocumented immigrants face while pursuing the American dream. While chasing a better life for themselves and their children, the film shows how damaging constantly changing laws and hostile rhetoric can be on some of our nation’s most vulnerable.

Verona founded Dreamer Moms USA Internacional, a support group for deported parents praying to reunite with their children. Member Alicia Frausto was separated from her children after being deported for running a red light after living undocumented in America for over 30 years. Six years later, she still finds herself trapped in a Mexican border city.

The film emphasizes the constant fragility undocumented immigrants live under and how one fateful moment can completely upend their entire lives.

Kaylin Olague is a College of DuPage student and second-generation Mexican-American. She remembers her sister being called a “wetback” when she was younger. She said when President Donald Trump got elected on an anti-immigrant platform, many Mexican-Americans just turned off the news and prayed.

“There’s always been an underlying fear of deportation with certain families working towards their citizenship,” said Olague. “There’s always been a tension, but in recent years we’ve experienced more. We tend to get looked at in a negative light. It’s sad because we are just like anyone else and trying to earn a living.”

As we swing into another election year, the film takes extra prominence as a reminder of how xenophobic rhetoric is fed to the public by politicians who dehumanize and stereotype immigrants. The immigrant struggle is turned into a political football. The film strips away the caricature to reveal the true lives affected by deportations and the legal limbo of the DACA program.

Professor of sociology Douglas Massey of Princeton University said in the film the demonization of undocumented immigrants is a calculated strategy by conservative politicians. The best way to incense voters is to make them feel their way of life is threatened by an “invading” and dangerous group.

“We have 11 million people who lack legal status in the United States,” said Massey. “(They) have lived here a long time, yet have no social, economic, political or civic right in this country. It’s unhealthy for a democratic country to have such a large population who are excluded and repressed.”

Hateful speech directed at undocumented immigrants accomplishes the objective of labeling all immigrants as illegal in the eyes of the public.

While campaigning, Trump told a fired-up rally crowd, “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

One of those good people is Julissa Arce, who because of a 2001 Texas state law, was one of the first undocumented immigrants allowed to attend college. Arce came to America when she was 11 years old.

“I guess I broke the law,” Arce said in the film. “With that came a lot of shame and feelings of guilt. (I felt) I was doing something wrong or I was wrong as a human being.”

While living a crime, Arce used fake papers enabling her to rise the ranks to become vice-president of Goldman Sachs on Wall Street. She attributed the Texas law for changing her life but still had to keep her illegal status secret after college. Arce argues justice and law are not the same thing in America. She said people fail to understand there isn’t a realistic pathway for many immigrants to become legal.

The fragility of her existence suddenly became apparent when she faced whether or not to visit her dying father in Mexico. Traveling while undocumented would mean having to be smuggled back into the country. Smuggling operations are very expensive and dangerous to risk.

“If I don’t leave, and I never see my dad again, am I going to be able to live with that?” said Arce. “The biggest cost of pursuing the American dream is never seeing my dad again.”

While deliberating over the dilemma, Arce’s father died while she was trapped in America.

Similar to the legislation that changed Arce’s life, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), an executive order by former President Barack Obama, enabled 728,000 undocumented immigrants to receive work permits and temporary protection from deportation. The program is currently frozen in an ambiguous state as its legality is argued before the Supreme Court.

Olague said providing education for immigrants is crucial for helping them break the cycle of poverty.

“DACA is so important because it helps a very under-appreciated community,” said Olague. “I’m so proud to be a part of the generation sending the most Latinos to school. People often are immediately inclined to think white students are smarter than Latinos. If we were to receive the same levels of education as white students, the possibilities are endless. People would believe a Latino could become a surgeon instead of just seeing a criminal.”

When Trump first announced changes to DACA in 2017, the College of DuPage Faculty Association said, “CODFA leadership maintains that changes to the DACA program are both cruel and unnecessary.”

In 2017, the Trump Administration also rescinded Obama’s executive order Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA) after the order was deadlocked in the Supreme Court. The order allowed parents who had been in America for more than five years, had U.S. born children or legal residents and passed a background check to receive deferred action from deportation.

Trump’s action put 5 million parents at immediate risk of deportation.

In a political compromise to bolster border security, 2.5 million people were deported under Obama’s tenure. Trump has continued the heavy-handed tactics, deporting over 256,000 people in 2018, according to the Washington Post.

The film shows how fears caused by draconian deportation bills like Alabama’s can spell tragedy for families. The Alabama law allowed police to question and detain any suspected individual without bond. Ismael Amaro and his wife Judith Zambrano had been living in Alabama for 12 years, raising three daughters.

“It is possible me or your daddy won’t come home one day,” said Zambrano to her daughters in the film. “They are little girls, and it broke their hearts.”

One of the young daughters commented, “I felt very sad. I don’t get why they don’t want us here.”

Steven Anderson police chief of Tuscaloosa said in the film the bill was surprising given undocumented immigrants hadn’t been committing large numbers of crime.

“When you have people that have been in your community (that long), they have become a part of your community,” said Anderson. “To all of a sudden target those individuals (to) deport was racist. This put us right back in the era of the ‘50’s and ‘60’s when we had a reputation for violating the rights of minorities in our state.”

As protestors carried signs outside the state courthouse reading, “We are human beings, not criminals,” parts of Alabama’s bill were stricken down as unconstitutional.

Conservatives argue if immigrants don’t want to fear deportation, they should come into America legally. However, for Mexican immigrants, legal status usually takes a minimum of 15 years. Olague said most families can’t afford to wait that long.

“My mother’s hometown in Mexico is currently held by a cartel,” said Olague. “I’ve never visited, because with the murder, rapes, drug and sex trafficking, it’s too dangerous. Immigration is a good thing to get away from the bad things.”

Olague said if America addressed its drug problem, there wouldn’t be demand across the border. She believes investing in infrastructure, legitimate businesses and education is the only way to provide opportunity for Mexican citizens.

The film says the “criminal invasion” label is ironic given the entire southwestern United States was stolen from Mexico during the Mexican-American War in 1847.

During the 1940’s, an open border enabled the circular migration of workers who came for 4-5 months before returning to Mexico. The inclusion of Mexican employment became the backbone of the agriculture, textile and food processing industries. They filled jobs white Americans were unwilling to work.

The criminalization of migrant workers and the militarization of the border beginning under the Reagan Administration in 1986 turned the circular migration into one of fixed settlement. The closure of popular ports of entry forced immigrants into dangerous non-populated crossings.

As headlines have been conflated on Mexican immigration, CBS News reported between 2009 and 2014 around 130,000 more Mexicans left America than entered. However, policies like Trump’s renegotiated NAFTA, designed to stop jobs from going to Mexico, take away employment opportunities for Mexicans. Workers will always go where the work is available for them. This shifts the flow of migration back to America against Trump’s intentions.

The film shows how the search for work can test the strongest of relationships separated by the border. Elia Cano runs La Paqueteria, traveling to Mexico once a week to bring mail between family members. The plight of her own daughter’s undocumented status preventing her from visiting family in Mexico inspired Cano to help restore others’ divided bonds.

For 15 years, Cano has traveled thousands of miles to reconnect families. She said time passes, but the feelings remain. One Mexican woman broke into tears as she read the words from her husband separated for eight years. “To the person I love most in the world. Happy birthday. All of my love.”