How will Illinois’ raised minimum wage affect student-aged workers?

COD President Brian Caputo on the future for student-workers

College of DuPage Interim President Brian Caputo – “We will have to keep re-evaluating tuition, but we will always be prepared to fund our student-workers.”

May 2, 2019

What is a living wage? Is higher pay for lower-end workers an entitlement or a fundamental right?

The College of DuPage pays student workers $8.50/hour and limits them to a 20-hour workweek. Students value the experience their jobs bring but often have to take a second job to make ends meet. This consumes their time and drastically impairs their commitment to schoolwork.

Come January, the college, along with the rest of the state, will raise the minimum wage to meet Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s new floor pay of $9.25/hr. This will increase to $10 in July 2020, followed by $1 increment raises until the minimum wage reaches $15 in 2025.

How will this affect student-aged workers and overall employment in the state’s economy? Will less-experienced workers find difficulty acquiring jobs? Will lower-level employees suddenly find their hours cut or their positions at risk?

Anthony Walker, Civic Engagement Officer on COD’s Student Leadership Council, understands the difficulty many students face balancing minimum wage work hours with schoolwork.

“You have to decide between extra shifts, working another part-time job, and if you can make up your school work at another time,” said Walker. “Should I skip class or put homework aside so I can make extra money?”

Walker hopes the increased pay will lessen the burden for student-aged workers. However, he learned from his experience working in retail, companies that have raised wages will try to increase efficiency and make up for losses by combining positions and trimming workers’ hours.

“What about wages that are already at $15/hr?” asked Walker. “I doubt employers will provide raises for everyone. It’s going to be harder for companies to stay competitive, and for the first couple of years, it will be harder for younger workers without the credentials to find employment.”

Walker said if student-workers feel aggrieved, the Student Leadership Council will drive attention to their cause until they can sit down with the proper people and try to reach common ground.

COD President Brian Caputo estimates each incremental raise in the minimum wage will cost COD an additional $200,000 per year. Currently there are 323 student workers employed on campus, with 252 employed under the College Work Study program and 71 under Federal Work Study. Both types of employees will follow the new state minimum. By 2025, the $15/hr will cost the school around $1 million.

Caputo called paying for the raises a balancing act, and said the positions currently employed are vital for the school. There is no expectation of position cuts or trimmed hours.

“We are incrementally raising tuition to cover a little of the additional costs, but we are also trying to grow enrollment and retention.” said Caputo. “We are trying not to overreact. We have a good financial nest egg we can shave off until we see the effects of our enrollment initiatives. Right now the economy is good, however, when the economy falters we can expect people to come and re-tool at the community college.”

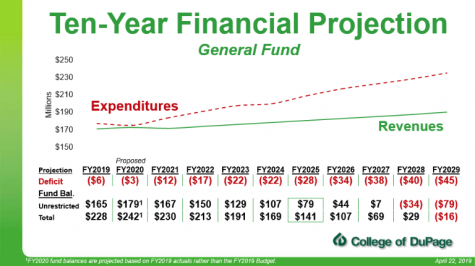

Caputo said the Pathways model and the Strategic Enrollment Management initiative should help decrease the college’s deficit budget. The school’s 10-year financial projection shows a continued deficit of expenditures over revenues. This model assumes a 1% property tax increase and also a $1 annual tuition raise. Enrollment is expected to decrease for the next couple of years, before rebounding due to the school’s initiatives.

“Our savings fund balances are hefty with money, but we can’t let the budget deficit go on forever,” said Caputo. “We will have to keep re-evaluating tuition, but we will always be prepared to fund our student-workers.”

COD will be giving a raise to $8.75/hr in the Fall for students who return for a second year of college work study. Caputo said the school hasn’t decided if they will pay another differential in January for those students.

One of these potential students is Stuart Burkhart, a student worker in counseling and advising. He said, unlike the strenuous balance in his past job in the fast food industry, working at the college provides him time convenience, allowing him to better manage his school work.

“The raised wages represent extra spending money and money to save for when I transfer to another college,” said Burkhart. “I work the full 20 hours; however, I don’t rely on the income for my living situation.”

Burkhart said because of the cost-effectiveness of student workers, the school might have to choose between administrative positions and the student workers if money became tight. He said the school’s predicament is similar to choices other small businesses and employers who hire minimum wage workers will have to face.

“If enrollment figures do not increase, it appears someone is going to be made unhappy,” said Burkhart. “I would rather be making $8.50/hr than zero. If the minimum wage increase threatens my job or my hours, I will be upset.”

Walker believes businesses need to get ahead of the curve so they can accommodate providing workers a livable wage and also prevent more experienced workers from leaving.

“Politicians need to not have such a one-sided debate, but talk to both business owners and workers,” said Walker. “The livable wage in DuPage County has been cited at $13.25/hr, however, I know from my experience the higher paid workers will not get a raise as well. When less-qualified employees get paid equally as the more experienced, in what world is that fair?”

Economics Professor Andre Guerra fears Illinois’ raised minimum wage will make it more difficult for students who come from lower-income households to find employment. He believes the benefits of providing a living wage should be weighed with the economic impacts.

“Employers will try to attract older workers with more experience making younger workers deal with increased competition for jobs,” said Guerra. “Hours available to younger workers will probably also decline. However, for students who can find jobs, the benefits of increased income are obvious. These workers will potentially not have to balance two jobs or extra hours.”

He said the new minimum wage could act as a stimulus to the economy because it boosts consumer spending, however, higher unemployment might completely offset the effects for the overall economy. He believes the state’s economic activity will see slowed growth but wonders how much, and how long these effects will last.

“After the first incremental raise, the state should have waited and judged the impact before continuously raising,” said Guerra. “The wage is rising over 75% in a six-year period. This is very difficult for businesses who rely on minimum wage workers. Will smaller businesses be able to cope? Will bigger businesses turn to more automation to save costs?”

Guerra said because any economists argue raising the minimum wage will create inefficiencies in markets, it would be more beneficial to create programs like a negative income tax or tax credits to help lower-class workers. However, he said because Congress never agrees, raising the minimum wage is seen as an effective alternative for giving a living income to all workers.

Political Science Professor Melissa Mouritsen believes legislators have been convinced by businesses that increasing the minimum wage will hurt the economy.

“In the U.S., business is our royalty,” said Mouritsen. “Legislators are far more beholden to business because they provide jobs, economic progress and campaign donations. Minimum wage should be viewed as more of a societal good (over an economic policy) because it’s good for everyone when people can afford to eat and pay their rent, and are lifted out of poverty and off government welfare rolls.”

According to the Economic Policy Institute 2019 Analysis, a $15 minimum wage would lift pay for 40 million workers, over a quarter of the nation’s workforce. The average year-round minimum wage worker would earn an extra $3,000 a year. The non-partisan institute claims this would drastically help the preschool teacher, construction worker or fast-food employee who currently struggles to survive on $20,000 a year.

Mouritsen believes America’s love of cheap goods has caused us to devalue and underappreciate our labor force.

“We don’t value labor because we can’t see the point of it anymore,” said Mouritsen. “A dollar hamburger, $5 t-shirt, brand new $125,000 suburban home; in order to get cheap goods, you need cheap labor. How could the people who make (these products) have any value themselves? A profit-driven economy rests on people not getting paid the true value of their labor. If the labor can be devalued, it is even more successful.”

Guerra believes raising the minimum wage threatens America’s obsession with cheap products because businesses may turn to increasing the price of goods to offset costs. He said consumers will absorb most of the costs of these higher goods.

Further absorption by consumers will come in raised property taxes. Pritzker estimated the plan will cost the state an additional $230 million by 2021, when floor pay is only at $10/hr.

State Republican legislators say besides cut hours and eliminated jobs, the law will cause businesses to flee the state, fail or cut employee benefits.

Guerra said businesses are not likely to flee because those subject to minimum wage workers, like fast food chains and other service industries have no incentive to move. He stressed the law only affects a small minority of those businesses’ workers. He fears small businesses will take the brunt of the law and many could fail.

“If we can find a way to employ every worker at a higher wage, the social benefits would be great,” said Guerra. “But for those workers who won’t find employment, the social impacts are negative. Further social assistance would be required to help those who are left with no job at all.”

Guerra cited an economic prediction showing for every 10% increase in the minimum wage, unemployment for teenage workers rises 1 percent. Pritzker’s law will raise the state wage 82%.

Guerra said the economic consensus isn’t clear because there are so many competing factors. He pointed to economist Alan Kreuger’s study into New Jersey’s raised minimum wage in the ‘90’s, which found no indication unemployment had increased as a result. Employment actually increased in businesses subject to minimum wage workers. However, he said businesses had two years to plan and could have shaved off workers before the study began.

He said there will always be too many moving parts for consensus, but most economists argue over how large the negative impact will be on unemployment. He said for similar reasons people should shy away from comparing our nation’s economy to other countries who have raised the minimum wage. He thinks Illinois will serve as a good experiment for what could happen on a federal level.

“The higher the cost of living, the lesser the beneficial impact will be for workers,” said Guerra. “The problem with raising the national minimum wage is the cost of living varies significantly across the country.”

Five Democratic presidential candidates have followed Sen. Bernie Sanders’ call for a federal $15 minimum wage.

Mouritsen believes the more voters show their support for a higher minimum wage, the more likely candidates will try to appeal to working-class and unionized voters. She said legislation helps, but the movement needs to be inspired from the ground up.

“Collective action is the key, but we lack the social capital to do this, said Mouritsen. “Although I see some hope on the horizon, change is hard when we argue about whether fast food workers should get $15/hr when paramedics get less. Real wages have not increased in decades. How about we pay both fairly?”