How Residential Schools Stripped Native Americans of Their Identities

COD launches its Native American Voices three-part webinar, starting with a lecture about residential schools and survivor experiences

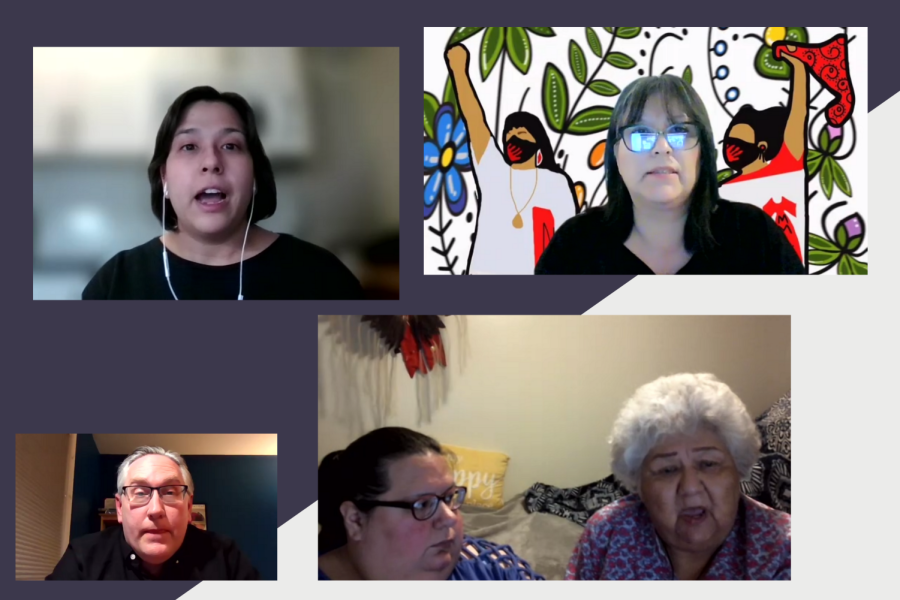

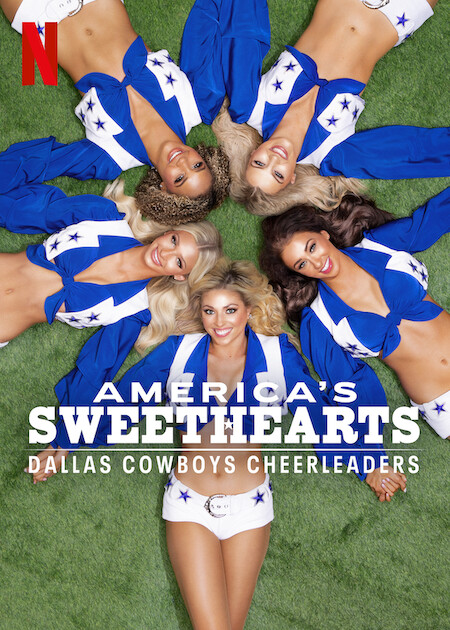

Graphic by Zainab Imam Pictured: Kaila Johnson (Top Left), Rachel Fernandez (Top Right), John Paris (Bottom Left), Joy Tiedemann and Nell-Lee Hawpetoss-Tiedmann (Bottom Right)

March 14, 2022

Nell-Lee Hawpetoss-Tiedmann is a member of the Menominee tribe, located in Northeastern Wisconsin. At a very young age, she was enrolled in a residential school– these were schools across the country that sought to eradicate indigenous culture from the United States. She spent the early part of her life having her culture erased and replaced by a new religion. Her birth name was removed from all documents and she was given a government name that was deemed socially acceptable. Everything from her name to her language was strictly forbidden.

“What happened was, from Kindergarten onward, we got our language beat out of us,” Hawpetoss-Tiedemann said. “And we got the Latin prayers of the church beat into us.”

Hawpewtoss-Tiedemann was the first of four speakers at a three-part webinar series, hosted by COD, about Native American history, highlighting Native American voices being the ones to tell that history. The first Webinar was hosted on March 9 and covered the history of residential schools and day schools. The event was moderated by John Paris, an associated professor of history at COD.

Hawpetoss-Tiedemann also talked in length about the humiliation and public shaming she and her peers had to go through because their culture was deemed inappropriate for school. She said the nuns of the school would bring students to the front of the classroom, and the rest of the students would call them names, such as “pagan.”

“My best friend would cry,” she said. “She cried because she had to call me a pagan.”

In a vast contrast, Hawpetoss-Tiedemann talked about how she received an abundance of love and support from her family and her community.

“Our culture was not a religion, it was a daily experience. Most of all you learn respect. This is how you respect things, this is how you respect yourself, know yourself and what you can do,” Hawpetoss-Tiedemann said. “When you’re little, you don’t know the difference between fear and love. All you know is what you feel. You didn’t know there was something in between.”

Hawpetoss-Tiedemann’s daughter, whose government name is Joy Tiedemann, spoke of the experience of growing up with the generational trauma of these residential schools.

“[My mom] went to a day school. My grandma went to a day school. They didn’t talk about it when I was younger,” Joy Tiedemann said. “I think I was in my 30s before anyone said anything about my grandma’s school experience, and all they ever said was, ‘it was a bad time.’”

Joy Tiedemann said that her mother made certain sacrifices for her children in order to save them from the traumas of the day schools.

“[My mom] made choices for us when she had kids. She moved us away from the reservation because she didn’t want us going to those schools,” she said. “I still ended up going to Catholic school, and I had some of the same experiences.”

The next speaker, whose government name is Rachel Fernandez, spoke about the lack of proper education about the dark history of the residential school and of the overall oppression of Native Americans in history.

“There are many people today who do not know the truth behind the genocide, or what genocide is, or what our ancestors endured,” Fernandez said. “Intergenerationally, this trauma has been passed down, and sometimes we don’t even recognize it. I didn’t recognize it in myself.”

Kaila Johnson was the last speaker to present. Johnson is the supervisor of Education, Outreach and Public Programming, Office of the Canadian National Center for Truth Reconciliation. She had a short presentation on the statistics of the residential schools in Canada, where her company is based.

“It’s estimated, over this history, there were at least 150,000 students that attended, but that number is likely much bigger. Because of the loss and destruction of records we won’t know that answer,” Johnson said. “Any map or statistic you see is really the lowest estimate.”

She also talked about the importance of survivor accounts in the collection of history.

“Abusers do not create records of abuse,” Johnson said. “If we want to know that true experience, the lived experience of residential schools, we have to go to those survivors and those families.”

Johnson provided resources for listeners to follow up with and learn more about the history of residential school, including The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition and the National Center for Truth and Reconciliation.

Fernandez took time to remind listeners that while this history is disturbing and horrifying, it is still important to learn about.

“I will not apologize for making you feel uncomfortable as I speak the truth, our collective truth. It is not my role or responsibility to educate you on histories that have been omitted. I put it on you, the listener, to find that history and learn,” she said. “Because when we are uncomfortable, we have the opportunity to grow. I challenge you all to grow and embrace that feeling uncomfortable.”

More information about the upcoming events and the full webinar can be found here.