Eric Blackmon Speaks to COD Students after 16 years of Wrongful Imprisonment

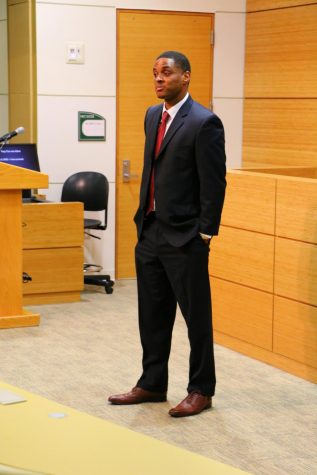

Eric Blackmon adresses an audience of students and professors in the William J. Bauer Mock Courtroom. Photo by Alison Pfaff

September 25, 2019

Eric Blackmon’s life had barely started when he was wrongfully convicted of murder in 2004. Just 23 at the time of his conviction, Blackmon spent 16 years in prison for the murder of Tony Cox. Blackmon shared his story of perseverance, hope and being “too stupid to quit,” at College of DuPage’s Constitution Day, hosted in the William J. Bauer Mock Courtroom. Set free only nine months ago, Blackmon shared his experiences.

Blackmon began his speech with the words “seven seconds.” That’s the exact amount of time it took for a judge to decide at the end of the trial that Blackmon was guilty of murder.

“For 16 years, seven seconds would ultimately go through my mind a million times. Sometimes I would just sit in that cell and just stare. We had a small wrist watch to tell the time, and I would just look at seven seconds tick by so many times,” Blackmon said.

After the shooting occurred, police gave two witnesses who drove past at the time of the shooting photographs two months after the occurrence, and asked them to identify a suspect. It’s not clear how or why Blackmon’s photo was selected to be among those viewed by the witnesses. But his photo allegedly is the one they identified as matching the shooter.

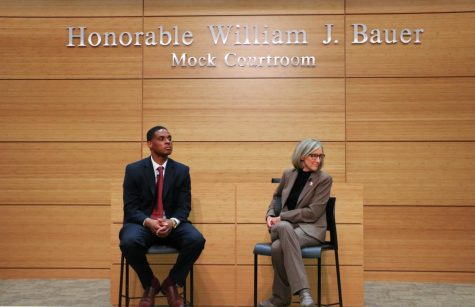

Daniel, who works at the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University Law School gave a general overview of the law in Illinois, as well as Blackmon’s case. She said witnesses to a crime become increasingly unreliable sources of information after more and more time passes from the actual event.

Photo by Alison Pfaff

“Please do this thought experiment after this session. Go walk out in your campus, take a look at someone you’ve never seen before, for five seconds, and write yourself a note on your phone two months from now to think back to that moment, and ask yourself, ‘Would I be able to recognize this person again,” Daniel said. “You can come to your own conclusion.”

Blackmon had no affiliation with any gang, the neighborhood where the shooting occurred or those involved. After coming into court to resolve a ticket, police officers asked him his name. Unknown to Blackmon, he had a warrant out for his arrest based on the two witnesses identifying him as the shooter via a photo lineup. He was then put in handcuffs and taken to the violent crimes unit of the Area 4 police department.

“This must be some type of mistake is what I thought,” Blackmon said. “I’ve never done anything wrong. They placed me in a small room for hours; they just sit you there. Nobody told me why I was there at that point. Never heard anything. Never knew anything. Nothing,” Blackmon said.

Police officers eventually explained to Blackmon why he was being detained in custody..

“We know you killed Tony,” an officer told Blackmon.

”It was earth shattering to me. I had to assume surely there was a mistake. This can’t be true. This can’t be happening. Not to me. I’ve never done anything wrong.”

Blackmon was grilled by police officers for hours and denied any involvement. Two years later, he finally had his day in court.

“I had all these witnesses that would say I was at this barbeque. I told my attorney about them. He’s going to get them right? Get all these people who were there. Well, I start a trial. I choose to go to with a bench trial. It was fast. It was quicker. It was easy, is what my attorney told me. There was no way the judge could find me guilty,” Blackmon said. “I wasn’t much older than you all. I hadn’t really had much experience with the court system. So we would take the word of the attorney, the person you’re paying to represent you. The person that’s supposed to be on your side. That’s what I did. I listened to him. He told me about all this great evidence he had found. How he had these other witnesses who also viewed the crime and said it wasn’t me. How he’d spoken to my alibi witnesses,and all of them would show up in court that day. Of course. Surely I couldn’t be found guilty, right?”

On Sept. 22, 2004 Blackmon was found guilty of the murder of Tony Cox.

“It brings tears to my eyes to this day to think about it,” Blackmon said. “That broke me. It wasn’t just me that it broke. It broke my family to hear my mother cry, to see her wail up in that courtroom.”

Blackmon’s attorney lied about the witnesses and never reached out to any of them.

“That first time you hear that door slam, and know you can’t walk out, 60 years. Man, it took everything in me to get up the next morning. To eat, it’s [even] hard to breathe,” Blackmon said.

Blackmon’s first appeal was denied. For the next 14 years, he began to research in the law library to prove his innocence. He read every book and case in the law library, given only one hour per week to access it.

“If it was there to be read, there to learn from, I definitely tried to learn it. That was my little piece of hope. That’s what I got up every day for that [and] my family,” Blackmon said.

People stopped visiting. Stopped calling. Blackmon said they got used to him not being there.

“For me, I found solace, I found hope in the things that I could do. And the thing that I could do, the thing that I could work on, was my case.”

Blackmon’s first petition sent to court was denied in 2008.

He continued to appeal the decision and improved his writing skills. The next one was denied.

For the next 3 years, Blackmon continued to study the law.

“I gave myself a quota of eight books per hour. I had to get through eight books, eight cases. Some of them long, some of them short. Some of them good, some of them bad. But I had to get through those eight.”

Instead of money, Blackmon asked his family to send him used books instead.

Eventually, Blackmon sent another appeal. Five months passed with a pending case. After 15 years in prison, he finally received a letter from the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals. His appeal was granted.

“That was like a drowning man finally getting a breath of air,” Blackmon said.

After receiving hearing after hearing, Daniel took the case.

Photo by Alison Pfaff

“I found every witness from prison,” Blackmon said. “I didn’t know we had that many resources, but I got phone numbers, addresses, called, tried to do everything I could. I was not going like before. I made sure people knew court dates. And I trusted [Daniel].”

After the first hearing, Blackmon waited six months. Finally, the judge made a decision.

“It was 23 pages, 2,361 words. It gave me my life back,” Blackmon said. “I read that decision at least once or twice a month. I read it to remember. I will never forget, but I remember so that I will never, ever take for granted any of it.”

On May 3, 2018, Blackmon walked out of prison for the first time in 16 years, released on bond.

On Jan.16, 2019 the Cook County State’s Attorney’s office dropped all the charges against him.

“There was no chance of me going back to that hell I had survived for all of those years,” Blackmon said. “I’m so grateful and appreciative to be standing here right now.”

Blackmon is currently a paralegal at the Northwestern University Center on Wrongful Convictions.