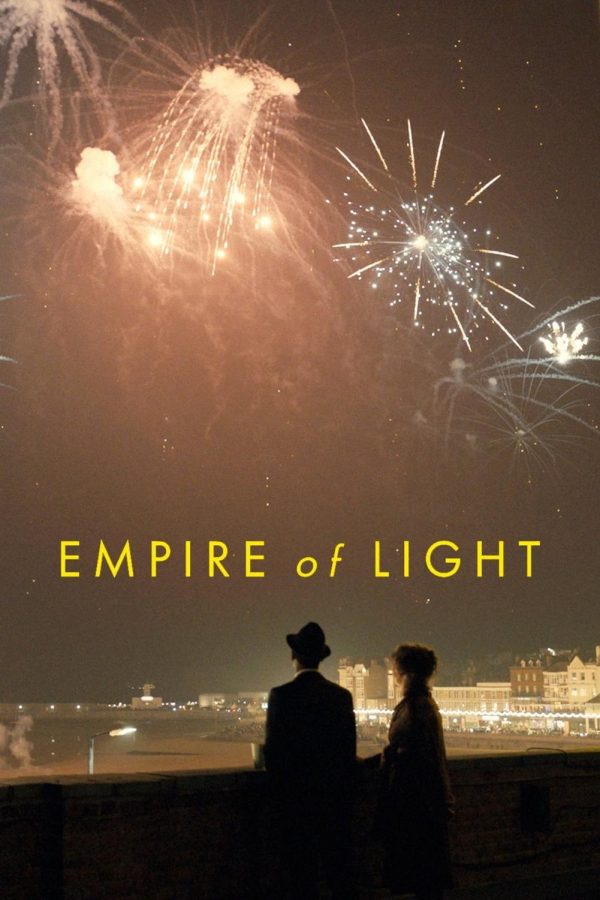

Acting, Editing, and Music Bring Life to “Empire of Light”

A story about many things, “Empire of Light” is a beautiful and at times touching watch.

February 20, 2023

“Empire of Light” opens in a theater with an antique popcorn stand, a ticketing booth and film reels piled on top of each other. It’s an early winter morning, and the Empire Cinema hasn’t opened yet. That is, until the soft-spoken Hilary (Olivia Colman) opens its doors for another day of work.

We’re then introduced to two more of the theater’s employees, Neil (Tom Brooke) and Janine (Hannah Onslow), as well as their boss, Ellis (Colin Firth), who’s having an affair with Hilary. The affair, as well as Hilary’s routine, seems to leave her numb – unresponsive to what’s happening around her.

This changes when Stephen (Michael Ward), a new recruit to the cinema, is introduced to Hilary, both of whom quickly hit it off while exploring the other dilapidated half of the theater and rescuing a wounded pigeon.

Their love blossoms into something that ensnares both of them into each other’s internal conflicts, but we know that their love isn’t meant to last. They’re an unlikely coupling who are at odds with each other. Hilary is in her forties but her life hasn’t been lived due to her struggles with mental illness, and Michael, a college-age teen with his whole life ahead of him, set back by the racism he experiences.

While this love story unfolds, we are shown different lines of inquiry throughout the movie, including one about Hilary’s history with mental illness, the racism experienced during the ’80s in England and the magic of the cinema, all of which felt underdeveloped by the end of the film. This is a case of trying to fit too much into a single movie.

What convinces me of its conceptual depth is the performances. Without Colman tearing up in one of the final scenes of the movie, the movie-magic element wouldn’t have had any weight. Ward’s anguish after being stared down by a prejudiced, old theatergoer played by Ron Cook brought the malevolent force of racism to the foreground. Otherwise, in both cases, we would’ve been left with scenes scattered over the movie’s runtime, too late to feel relevant and disconnected from the other themes at play.

Related to this was the inclusion of Crystal Clarke’s character, Ward’s forgotten-then-remembered love interest. Clarke’s character seems to appear for no reason other than to realize a comment Ward had made earlier in the movie and create further division between him and Colman. I would say the same of Tanya Moodie playing Ward’s character’s mother, whose inclusion in the film is too late to have been as important as she was intended to be. This, I felt, was especially clear in a scene near the end of the movie where Moodie’s character finally meets Colman’s, but her reaction didn’t affect me as a viewer.

As an end note to my critiques of the movie, I thought the dialogue didn’t give the characters enough depth, nowhere near as much as given by the performances, specifically those of Colman and Ward. Colman, giving the role her usual gravitas, turned Colman’s character into someone we take seriously and empathize with. There are a few scenes in particular that could’ve come off as absurd, but Colman grounds them.

To highlight one of them, while giving an on-the-spot speech, Colman’s character stammers with lipstick on her teeth, and it made me feel embarrassed for her, as though I was a friend nearby cringing while it played out. Another scene, in which Colman erupts in anger and destroys a sandcastle, is delivered with a sincerity that left me with the impression that she regretfully couldn’t recall why she had done it.

Ward’s character thankfully avoided becoming Colman’s foil. Scenes where she might have stolen my attention were instead drawn to his expression, which showed more depth than the writing implied. For example, when Ward is sending Colman’s character off after an unsettling day at the beach, you can see in his face a reproach that turns into doubt later in the film. Another is when, while angrily walking away from the theater, Ward’s character tells Colman exactly what made him so upset simply with his pronunciation of one line.

The cinematography is great, as well, done by the legendary Roger Deakins. I don’t think there’s a shot in the movie that isn’t beautiful. The focus is always on what conveys the meaning in the scene best. One, for example, is near the beginning of the film, where Colman’s character is turning on the theater’s lights. Once lit up, we see the main entranceway in its glamorous, unfiltered beauty.

An additional shot is when Colman is staring at a prescription in her medicine cabinet, with her face reflected in its mirror. From behind, we see her expression while she looks at it, contemplating whether she wants to take it and how it has affected her. To go on, a third angle is when Colman’s character, in the foreground, is picking up excess popcorn after a screening with Brooke and Onslow, who are in the background. From this set up, we can tell that Colman’s character is listening in on the two’s conversation. Something as seemingly minor as this shows a coalescence of audio, visuals and writing that creates a natural appearance and flow.

Another important aspect of the film’s creation that’s immediately apparent is the editing by industry-veteran Lee Smith. What stood out to me was the coinciding audio and visuals, specifically, as the theater’s lights were being turned on, with each light coming on, another piano note played. I thought the same of other scenes where the soundtrack played once a certain point had been reached in the story, such as when Colman’s character was walking home in the cold after leaving the theater for the night.

The soundtrack was great, another for the duo of Atticus Ross and Trent Reznor. I can distinctly remember the music being important in three scenes: the first being the opening scene (“8 AM, Christmas Eve”), the second being one of Colman’s: walking from the theater at night (“The Sea, The Sea”), and the third is when she’s destroying the sandcastle as I described before (“Clouds Appear”).The third song felt overbearing in the context of the scene, but the other two, as well as the rest of the soundtrack felt like it fit the movie’s visual and writing style well.

The movie was trying to do too much, but its constituent parts worked well enough to create a thought-provoking tale about a life reinvigorated by a new love.