Why celebrity deaths make me cry

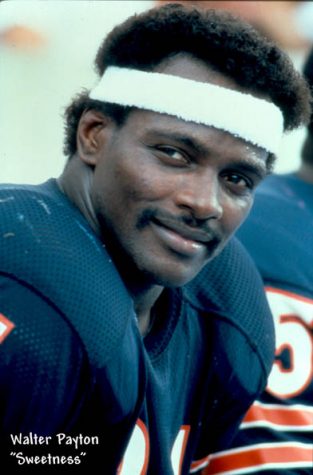

Arnold Palmer’s (pictured right) death at age 87, represented for many, the end of a golden era

May 24, 2018

I found myself crying harder than I had in years. Anguish welling in my eyes, an inescapable depression streaming down my face.

How could Bowie be gone?

Close people in my life, even family members, have died. Yet, here I found myself in a catatonic stupor of disbelief. All over someone I never personally met.

What is it about celebrity deaths that evoke such visceral reactions of sorrow?

We don’t know them personally, yet we feel like we do. Memories of them become entangled with our own. As we mature, their influence becomes integral to the self-definement of our own identities and subjective realities.

College of DuPage Professor of Psychology Ken Gray discussed the rush of nostalgia upon hearing a song by a musician who had formed an intimate relationship with his life.

“This is one of the fundamental principles of memory: the songs serve as retrieval cues for these autobiographical memories. Because these events were all meaningful, the memories of those events include pleasant emotions, which is essentially what nostalgia is,” said Gray.

He continued, “When a celebrity with all of these memory associations dies, we are faced with the fact that we will never be creating new memories with the celebrity. We feel a sense of loss, or grief. This is someone with whom we feel as if we have a personal relationship, so the grief is especially intense.”

Our idols have also been there to comfort us in our times of need. We share them in our intimate moments, especially moments of weakness. We reminisce upon the nostalgia of pivotal moments in our life that provided us with strength. These moments can define the perception of how we view ourselves.

Losing a cherished celebrity becomes losing a part of yourself. This loss triggers existential introspection. We are reminded of our own mortality and the fragility by which our lives abide.

Sympathy is especially powerful when their cause of death resonates with our personal lives. Robin Williams’ death resonated with those who battle dementia or depression, whereas the death of pro-football player Dave Duerson from the concussion instigated, degenerative brain disease, CTE, resonated with me on a more personal level.

Celebrities connect us to our memories and our memories serve as the fabric connecting us to our friends and family. When a celebrity dies, this connection to those we love is hindered. As we become further from those we love, these severed connections isolate us.

When legendary golfer Arnold Palmer died, I felt a living connection with my passed grandmother, who was an avid golfer, was lost. This made her feel even further from me.

This isolation also damages the self-image we have constructed for our identity.

We grow up with celebrities representing the pinnacle of our desires. We identify with those who possess similarities to how we perceive our current or ideal versions of ourselves. By idealizing them, we immortalize celebrities to represent higher-beings, living their lives free of the flaws we possess. When they die, this illusion is shattered. We are forced to see life in the cold light of reality.

We become upset when our self-defined, socially-constructed worlds become disrupted.

This becomes especially damaging when the celebrity represents the better-half of our externally-dependent identity.

Gray explained, “Mass media has given us the opportunity to feel as if we are getting to know celebrities personally, and when we discover these similarities, or have these pleasant experiences associated with them, we can feel as if we are developing a relationship with the celebrities. Psychologists refer to these as ‘parasocial relationships’— completely one-sided relationships, in-which one party does not even know the other side exists. These relationships can feel as real to us as those we have with people we see everyday. Thus, when a celebrity with whom we have a relationship dies, it is very much like a close friend has died.”

When you give most of your time and thought to icons, emotionally invested parasocial interactions form. Because the celebrities have been idolized, they help construct our identity, self-image, political beliefs, fashion, attitudes and behaviours around others. They permeate our choices influencing the very nature of who we become. The more you glorify a celebrity, the stronger this parasocial relationship and the greater their influence upon your identity.

I find it no coincidence my political ideologies mirror those of my favourite television character, Alan Alda’s Hawkeye Pierce, from M*A*S*H. You witness a more pronounced and better version of yourself, and then strive to become this more refined form.

We live from one image to the next. When these fabrications are utilized for indulgence, we take their lives to fill us with a higher self-importance. We use this grandeur to compare ourselves with those around us.

We believe publically grieving makes us appear more sympathetic. In our pop-culture driven society, the fabricated-sympathy is inescapable. This behaviour often escalates into a pretentious form of ‘competitive grieving’. We overemphasize our connection to the celebrity in an effort to improve our social standing. This embellishment inflates our level of exception and uniqueness. The more the individual grieves the death of an idol, the more special their perception appears. This perception defines their image to both others and themselves.

This embellishment both occurs when the celebrities are with us, as well as when they pass away.

Psychologists call this tendency, ‘basking in reflected glory,’ or “BIRG.” BIRGing occurs when an individual associates themselves with successful, powerful and influential people, sports teams or social groups, so that the idolized accomplishments become the individual’s own glory. The individual is then able to share credit for their successes, and further their perception they put out into society. This enhancement furthers the perception of their identity, stimulating their self-esteem.

When the Chicago Cubs won their first World Series in 108 years, I celebrated like I was a member of the team. However, when my ego’s perception is stripped away, the reality is, I am just an average fan of the team. I personally had won nothing.

When Prince died, many proclaimed to be massive fans of his. Their supposed association with his greatness, correlated to their greatness. However, in reality, most only knew his bigger hits.

By attaching to celebrities’ imagery, we gain an existential importance and uniqueness compared to those around us. BIRGing is linked to ‘social identity theory,’ which postulates the individual’s conceptualized identity derives from perceived affiliations with social groups of interaction.

However, this perceived affiliation isn’t always a cognitive fabrication. Individuals strive against isolation by pursuing what sociologists call ‘social solidarity.’ When we unite in conversation, it reminds us of our social oneness. Celebrity deaths provide the platform to congregate and talk about a subject which is normally considered taboo to discuss. Discussing something so vital to our existence helps us better understand ourselves.

The solidarity in sympathy exemplified for the 16 deaths and 13 injuries resulting from the Humboldt Broncos junior hockey bus crash, permeated cultural divides and united us in grief.

Whether through social solidarity or as individuals, mourning the loss of public figures illuminates our emotional inner-depths. We seldom reach their full capacity, yet contemplating and grieving loss provides us access to a greater self-understanding.

We exhibit phenomenal sympathy and empathy, yet in the end, we are always grieving for ourselves.