What changes will the Jason Van Dyke murder verdict bring? (“Do the right thing”)

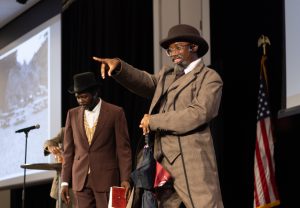

Co-presidents Djimon Lewis and Taria Murphy of the Black Student Alliance at College of DuPage

October 16, 2018

Poised to riot, poised to protest, the city released a collective breath as the verdict was announced. Former Chicago police officer Jason Van Dyke was found guilty of second-degree murder in the Oct. 20, 2014 shooting of black teenager Laquan McDonald. He was also found guilty on 16 counts of aggravated battery – one count for each bullet that pierced the teen’s body.

Djimon Lewis, co-president of College of DuPage’s Black Student Alliance, blames racial bias and prejudice within the Chicago Police Department for escalating situations with tension.

“The media plays up the black-on-black crime and the thug culture,” said Lewis. “Then you put police in communities they are not from; they don’t understand people from the community on a personal level. They start manufacturing assumptions about the people.”

Co-president Taria Murphy said the conviction was historic and could represent a turning point in the city’s race relations.

“We are finally seeing progression. A group of people felt for so long their voices did not matter, and even if the evidence was on their side, something would hold them down. This unveils what is going on in our inner-cities. It will start a better relationship between police and African American communities and open dialogue on how police brutality affects communities.”

Former Wheaton Police Chief James Volpe is the current director for COD’s Suburban Law Enforcement Academy. He teaches the next generation of officers how to handle pressurized situations.

“(The verdict) opens the eyes of every police chief, making them realize we have to keep our officers well trained,” Volpe said. “This can happen everywhere. We need to prepare our officers to handle that exact type of situation and not overreact. I’ve told many officers, your use of force was unjustified; here’s your discipline. When something like this happens, jump on the case, don’t cover it up. Do the right thing.”

Volpe has taught Use of Force courses for supervisors, officers and police recruits for 20 years. Recruits learn the fundamentals, and officers learn when force is reasonable and constitutional. Supervisors are taught how to review and evaluate whether the use of force was reasonable, and taking disciplinary action if necessary.

Director James Volpe of College of DuPage’s Suburban Law Enforcement Academy

He believes proper training can ensure public complaints against an officer’s conduct are effectively handled by supervisors.

Volpe also believes Van Dyke’s misconduct is proof of poor training.

“There’s no way you put 16 rounds into a person; you just don’t,” Volpe said. “That’s not how we train. We train to fire and assess, fire and assess. If the guy is down, you don’t keep shooting. Sixteen rounds, with no other officer firing, you have a poorly trained officer. He should have been fired the day a supervisor saw that video.”

Following outrage from the shooting, a U.S. Department of Justice investigation under then-Attorney General Loretta Lynch found Chicago police were poorly trained, routinely violated the constitutional rights of city residents, used excessive force and racially discriminated.

Statutes dictate every officer annually attends use of force training, and the state training board has made 40-hour certification in crisis intervention training mandatory.

“We could use more scenario-based training,” said Volpe. “Putting officers in high-intensity situations and training their body how to react. (At COD), this is done in our control arrest tactics bloc. We have both a physical and legal aspect of teaching use of force. We teach what the legal parameters an officer can do are. What the Constitution says and what state law says.”

Through such training, the next generation of policing can face a similar situation as Van Dyke and not take away a life.

Volpe believes change stemming from this verdict will be an emphasis on communication.

“If you are mentally ill, disabled or from a different culture, the officer needs to understand who they are dealing with,” Volpe said. “What does the individual think is happening to them? Was there something wrong with Laquan McDonald that night? He had a knife, but why was he not following police commands to drop it? Did he need special treatment? (Don’t be) so fast to conclude the person is a threat to the officer. Maybe the person is trying to get away from you; maybe they are trying to deal with an internal problem. If (the officer) is insensitive to that, the officer can do the wrong thing. Can I talk to you? Can I figure out what’s wrong with you? There’s a way to react through communication instead of just shooting.”

Volpe pointed to crisis intervention training and a neurobiology class taught at COD to help officers deal with the mentally ill. He said a person with a weapon could be a bigger threat to themselves than to the officer. The objective is to communicate and get them to drop the weapon.

The Suburban Law Enforcement Academy teaches scenario-based training in the VIRTRA simulator. Here, reporter, Joey Weslo exhibits a lack of training in being too eager to point his weapon

He believes internal change stems from hiring candidates who are psychologically sound and don’t have personalities prone to bias and prejudice.

“In my experience, race has never been an issue,” Volpe said. “Intensity is the issue. If the person I’m dealing with is African American, they might take my over-anxious state as being based on race, but it’s really fear stemming from not being trained well enough.”

Murphy also believes training can help eradicate discrimination.

“Officers need to have more sensitivity training and know exactly what type of neighborhoods they are getting into. There needs to be culture training and better rhetoric and body language understanding.”

Lewis said officers should be recruited from the neighborhoods they are expected to protect.

“Hopefully someday we will progress to people policing their own people. (However), in some of these communities, joining the police would be seen as betraying your own people.”

He blames this mistrust on decades of racial oppression and a current lack of communication between the police and the African American community.

“(CPD) needs to survey in what situations do people feel police are abusing their power? How can they make African American communities feel safer? Are they using force too much? Is their rhetoric too excessive? There needs to be a culture shift from being just police, to being friends and protectors of the community,” said Lewis.

Murphy believes representatives from the African American community should go into the department to create open dialogue.

“Both sides have assumptions of each other because they aren’t listening to each other. The department needs to be more socially active in the communities they police.”

Following the DOJ’s investigation into the CPD, a court-mandated consent decree dictated reforms for the department. Advocacy groups like Black Lives Matter and the ACLU were given a role in shaping the litigation.

Lewis believes activists need to stay motivated and inspire change.

“Their voices are being heard, but that’s because activists have forced the authorities to listen. There wouldn’t have been any change if the video never came out. Civil rights lawsuits need to continue. The city won’t change unless adequate pressure is applied by activists to do the right thing. I don’t want to be loaded into a false sense of security by this consent decree. Continued pressure needs to force a change of culture.”

Inspired by recent killings of African Americans by police officers, the Black Lives Matter movement has polarized American culture over its demands to end police brutality and systemic racism within police departments

He addressed the cover-up trials for three officers accused of protecting Van Dyke. He believes the department needs to be more transparent and accountability must come from the superintendent down.

Volpe said outside supervision can be difficult because the average citizen doesn’t understand the constitutional use of force. However, he believes if the watchdogs have the competency to analyze complaints, they can help build trust within the community.

“When police issue orders, they have the public’s safety at concern. If you comply with those orders, an officer should never have to respond with use of force. There’s a legal framework to protect you if you feel the officer has acted unlawfully. You can bring a lawsuit against the officer. If you have a good case for unlawful conduct, any civil rights attorney will take your case for free.”

He believes people resist when they mistake an officer for acting unlawful. Police are bound to constitutional parameters of conduct. He pointed to Wheaton’s citizen police academy designed to teach the public better understanding of police legal conduct.

An officer can legally use deadly force if he, or a bystander, is threatened with deadly force.

“The use of force often looks terrible. It’s hard to explain to the public there are constitutionally mandated levels of force an officer is justified to use,” said Volpe.

Volpe explained, Grant v. Connor (1989) dictates when an officer’s use of force is justified. A higher-level force can only be used for a higher-level threat. The use of higher-level force to lesser threats is deemed excessive and illegal.

Formed as a reaction to perceived attacks on the integrity of police departments, movements like Back the Badge, Police Lives Matter and All Lives Matter argue the public doesn’t comprehend the dangers and difficulties that come with the job

“Second-degree murder is first-degree with a mitigating factor. Van Dyke thought he was justified, however, the court concluded his wasn’t a reasonable justification,” said Volpe.

Volpe believes the consent decree’s initiatives on better training, hiring and transparency are positive steps in addressing racial stereotypes and bias within the department.

Murphy discussed the opposition to the decree some officers and the police union have espoused.

“We are advocating for these changes so there won’t be fear. Police officers have said they are fearful because this will make their job harder. How can you be trained to encounter different scenarios but as soon as you are documented, or have a body-cam, your training leaves you?”

Lewis pointed to President Donald Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ objections to the decree. They argue the decree will lead to a rise in murders and violent crime.

“Anytime you have a power-imbalance it causes issues. The police are already in the law’s favor, but the power is lost when it comes to the people. Any reluctance by the federal government not to infringe upon the sovereignty of the (CPD) is a disservice to the citizens. When Trump advocates for bringing in the National Guard, it’s hypocritical.”

Lewis pointed to Trump’s advocacy for stop-and-frisk policing.

“Stop-and-frisk propagates racial profiling. Police officers act upon the presumption an individual will already commit a crime. This is just going to agitate the community and make them feel they are being targeted even more.”

Volpe views stop-and-frisk tactics as unconstitutional.

“I’ve read the whole 235-page consent decree. There’s nothing the courts are demanding the (CPD) do that is out of line. If a police officer is going to shy away from doing their job right, then they shouldn’t be a cop.”

Lewis believes if Trump wants to end Chicago’s violence, education in the CPS needs to be better funded, teachers should be paid better and after-school programs should be provided. He believes the city needs to be desegregated, with dependable jobs being provided in the poorer neighborhoods.

Addressing the polarization that often highlights the city’s divides, Volpe expressed the All Lives Matter mantra.

“No cop ever wants to take a life. Shootings are devastating to the emotional well-being of the police officer. When you go through the high-intensity training, you don’t see race; you only see a threat. We focus on the weapon.”

Lewis said All Lives Matter undermines the legitimacy of Black Lives Matter’s cause of fighting racial oppression and discriminatory police brutality. He warned of the violent caricature people often perceive the movement with as being the product of biased media. He believes understanding can come by truly listening to the group’s message. Mutual respect can help ease the polarized dichotomy. One can support police safety and the law, while also pointing out systemic discrimination and brutality.

He believes the verdict has made many reflect deeper upon their own assumptions.

“You realize nobody is above the law. As a black man from Chicago, if this case would have resulted in not guilty, I would have lost faith in our judicial system completely. This verdict provides me with hope,” said Lewis.

He said he is concerned of the sentencing difference between first and second degree murder.

Lewis is concerned about Van Dyke possibly getting off with a lesser punishment because of the sentencing guideline differences for first-degree versus second-degree murder. However, he sees Van Dyke’s verdict as part of the larger picture.

“True justice is a change in culture within the police department. If the verdict results in a better world for the African American community and police officers, then that is true justice.”