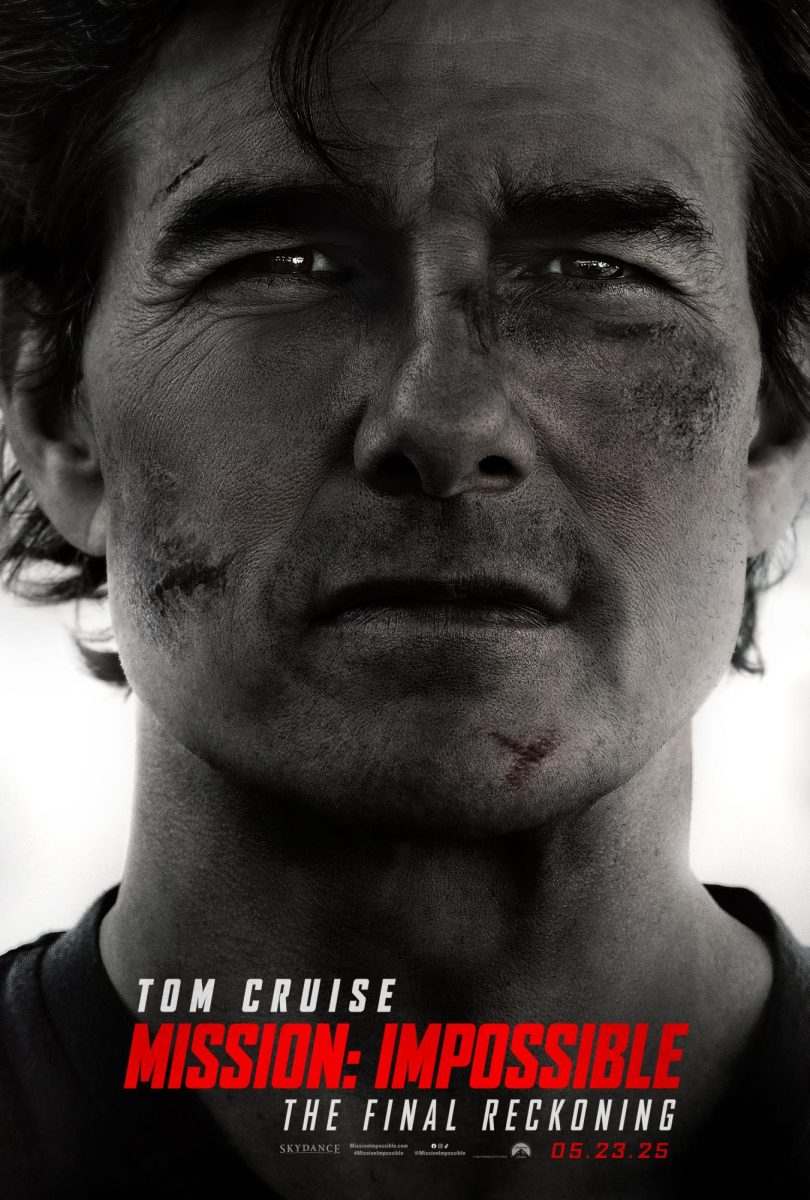

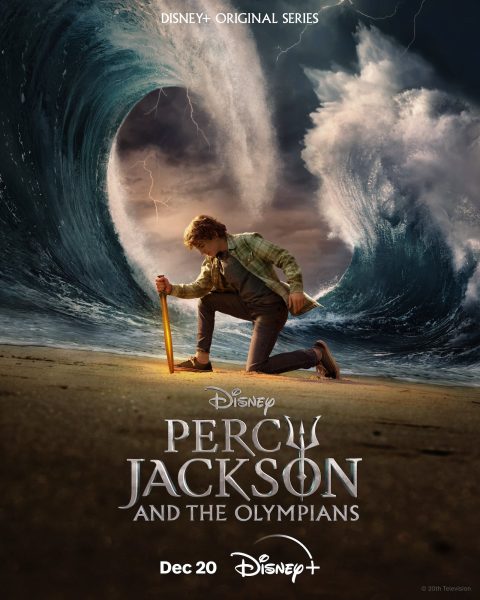

Fantasy has always been my favorite genre, with iconic series like “Avatar: The Last Airbender” and “Percy Jackson and the Olympians” playing pivotal roles in my childhood. However, the recent wave of big-budget fantasy adaptations has left me largely disappointed and disillusioned with the direction the genre seems to be heading.

Despite their visually striking resemblance to the originals, these adaptations lack the heart, soul and humor that made the originals so incredible. The storytelling of the “Avatar” animation and the world-building of the “Percy Jackson” books were irreplaceable, highlighting a fundamental truth: no amount of money can compensate for a lack of depth and understanding of the source material.

There are common threads of issues through both shows, the first being the writing. The dialogue often feels stilted, lacking the natural flow and wit found in the originals. Even worse, there was excessive exposition and information dumped into each episode, overcrowding the plot and often replacing the nuanced storytelling that drew fans in.

For “Avatar: The Last Airbender” (ATLA), issues were apparent from the first episode, where they redid the intro to extensively cover the Avatar world and its reincarnation cycle (through a robotic, ear-grating female voice that is supposed to be Avatar Kyoshi) and later through Gran Gran, Katara and Sokka’s grandmother. One of the show’s most glaring exposition missteps also occurs right at the beginning, as the show begins 100 years before the present timeline, right before the Fire Nation started the war and the air nomad genocide. Instead of immersing us in the present with our main characters and allowing Aang’s backstory to unfold naturally through flashbacks, we learn it all immediately and gruesomely.

In the case of “Percy Jackson,” they tell the audience about the magic and mythology in their world through tedious, exposition-laden dialogue, without allowing the audience to learn through the characters’ interactions with them. Whenever the trio faces a new monster or mystery, like Medusa or the Lotus Casino, they quickly figure out what it is and recite these obscure facts to the audience.

For both shows, the amount of info-dumping makes it feel like the creators no longer trust the audience to remain engaged in suspense, opting instead to provide all the answers upfront and robbing the shows of mystery and intrigue.

Both adaptations also suffer from pacing issues, with episodes feeling rushed, leaving the characters and story little room to breathe despite their lengthy episodes.

For instance, the scene on Zuko’s ship, when Aang is first caught and prepared to be taken back to the Fire Nation, lacks coherence and the excitement of the original. Without any buildup or explanation, Aang somehow appears in Zuko’s room, and after conveniently finding scrolls that detail where to find temples, simply runs out of the room. He faces no conflict, which means we don’t get to see a cool fight scene like the original.

Then, the narrative swiftly shifts to the Southern Air Temple, where Aang discovers Gyatso’s corpse, enters the Avatar state, has a touching, but unnecessary, moment with the spirit Gyatso and resolves the conflict abruptly.

In the Percy Jackson show, the rushed pacing led to key elements being glossed over or condensed, particularly in the early episodes. This included important character introductions, establishment of the setting, and pivotal moments that set the tone for the entire series. For example, Grover and Percy’s relationship at Yancy Academy felt undeveloped, as well as Annabeth and Percy’s relationship at camp before they went on the quest together.

However, my biggest issue is with the portrayal of certain characters.

First, I want to praise both adaptations for their casting decisions, as the Percy Jackson show had color-blind casting and found actors perfect for their roles, and the ATLA live-action hired indigenous actors to play indigenous characters, learning from the whitewashing of the 2010 movie. However, good or accurate casting cannot compensate for deeper issues.

In both shows, all the characters felt strangely static. While they’re repeatedly told how they should develop and what they should do, they don’t seem to grow or change at all, largely because they didn’t have many flaws from the beginning.

This brings me to my next critique: both adaptations significantly altered certain characters, removing their flaws in an attempt to make them less “problematic.” This was particularly noticeable in their female characters like Katara and Annabeth, where flaws that have historically been heavily criticized by fans were removed, perhaps to turn them into ‘better’ female role models for young viewers.

For instance, Katara, who is known for her anger, ambition and pride in addition to her nurturing personality, became much more docile and diplomatic. This change was apparent from the first episode, as the circumstances in which Sokka and Katara discover Aang are changed. Originally, Katara and Sokka discover Aang while arguing as they canoe through the icy waters of the South Pole. When Sokka makes a misogynistic comment, Katara cannot contain her fury or control her water bending. Standing up for herself, she shouts at Sokka as he tries ineffectually to calm her down and accidentally cracks the ice that Aang was frozen in, inadvertently freeing him from his 100-year slumber.

However, in the live-action, the siblings are not fighting when they find Aang stuck in the ice, though they still free him accidentally.

The show-makers also chose to downplay Katara’s ambition, making her want to go on the journey solely to help Aang instead of also seeking personal growth and mastery of her water-bending abilities. This transformation is disappointing, as Katara in the original series was a multifaceted character who challenged stereotypes and societal norms. Her anger and ambition were crucial to her development, driving her actions in the Avatar world and making her an icon for little girls everywhere. The decision to soften her character robs her of her complexity and undermines the message of empowerment that she represented.

Annabeth is also softened, as she is much more stoic and wise, with less dialogue and banter than in the original story. They removed her complex traits, like her impulsiveness and pride, which made her character so relatable and real. They also removed some integral parts of her personality that were relevant to certain plot points, like her fear of spiders (though they mentioned it) that caused issues in the Tunnel of Love scene or her love for architecture, which was the motivation to visit the St. Louis Arch.

By softening their characters, both adaptations fail to capture what made Katara and Annabeth so compelling, stripped of their relatability and complexity.

Moreover, some of the character and plot changes contradict the original plot arcs.

For example, the showrunners changed Aang’s backstory. In the original series, we learn that Aang was flying in the storm because he was running away from his duties as the Avatar. By leaving, he left the air nomads to suffer genocide at the hands of the Fire Nation, a consequence he will always mourn and regret, which sets the stage for his growth as he learns to accept his responsibilities. But in the adaptation, they make his disappearance seem like he was going flying to clear his head and planned to go back to the air temple soon. This change means that crucial parts of Aang’s growth in the first season, like accepting his role as the Avatar and learning from his mistakes, are left out entirely, weakening his character depth and journey.

Another notable difference lies in the pivotal Agni Kai, the Fire Nation duel, between Zuko and his father, Ozai where Zuko gets his scar. In the original series, Zuko refuses to fight back due to his deep respect for the Fire Nation’s hierarchy, showcasing the internal struggle he faces. Yet, in the adaptation, this critical moment is altered, as Zuko chooses to fight back, diminishing the complexity of his character arc and the message about abuse.

In Percy Jackson, the show made changes to the ending of the first book.

In the final scene, Percy and Luke duel with swords, revealing Luke as the Lightning Thief who has been plotting against the gods all season. Unlike the book, where Luke tries to poison Percy, here Percy simply cuts him and apologizes. Annabeth, hidden by her magical cap, intervenes to protect Percy from Luke’s counter-attacks, showing her heroism and desire to overcome her weaknesses.

However, while this change portrays Annabeth positively, it alters her narrative arc. Throughout the series, Annabeth struggles with her feelings for Luke, torn between loyalty to him as a friend and realizing his betrayal. Her belief in Luke’s redemption is a significant part of her character, showing empathy and forgiveness. Saving Percy shifts focus from her internal conflict over Luke’s redemption and loyalty to the gods and Percy. Additionally, this change reduces the impact of Annabeth’s growth, as overcoming her hubris is central to her character development. By showcasing her heroic moment early, the narrative misses a chance to highlight Annabeth’s growth and ability to overcome flaws in later seasons.

Also, for ATLA, one of the things I loved most about the original series was its ability to seamlessly blend humor with hardship, creating a dynamic and engaging narrative. However, this element seemed to be missing in the adaptation. Characters like Sokka, who were known for their age-appropriate immaturity and comedic relief, came across as overly serious. Many of the lighthearted moments from the original series, which provided much-needed relief from the heavier themes, were also noticeably absent, contributing to a lack of balance in the overall tone of the adaptation.

Moreover, I was particularly struck by the excessive violence depicted in the adaptation, which felt unnecessary for a children’s show. Scenes showing characters being burned alive seemed to be included solely for the sake of showcasing special effects. This departure from the original series, which aimed to portray the devastating effects of war without glorifying violence, felt jarring and out of place. Instead of focusing on the aftermath of conflict and its emotional impact on the characters, the adaptation seemed to prioritize graphic violence for shock value. As a fan of the original series, this emphasis on gratuitous death and violence felt like a misunderstanding or even an insult to the source material.

Similarly, the Percy Jackson adaptation lacked the humor and irreverence that made the original engaging and relatable to teenagers. By taking itself too seriously and adopting an overly angsty tone, the adaptation failed to capture the fun of the books.

Much of the success of the original works was not just about the story but also about how it was told in their unique mediums. I believe the key to successful adaptations, especially of fantasy series, lies in going back to basics: respecting the source material and letting the story guide its presentation. Creators should have more faith in their audience, understanding that viewers can handle complex narratives and appreciate subtlety. By staying true to the essence of the original stories and characters, future adaptations can captivate audiences, new and old. Until then, I’ll stick to rewatching and rereading the originals.