Race Problem in Judicial System

Judge Tan Ikram visited COD to discuss diversity in the courtroom and why it matters.

February 27, 2023

Now more than ever the spotlight is on the police. Especially on issues concerning race.

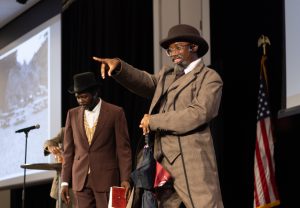

This past Thursday, COD welcomed Judge Tan Ikram for a talk about this very topic, titled “Diversity in the Judiciary and Why It Matters.” The presentation took place at the HEC’S mock courtroom where Dr. Mark Curtis-Chavez, the Provost at COD, introduced Ikram to the audience, consisting of students and professors.

“Why am I here? Well, you started it.” Ikram began his talk, referring to the Black Lives Matter movement of Summer 2020. “The death of a Black man here spread all across the world. In England, a lot of very angry people took to the streets. A lot of damage was done. A lot of people were arrested. There were a lot of protests. And we started thinking, again, about the legitimacy of the way the criminal justice system works. In particular, we’ll be looking at the police.”

Ikram, a law graduate from Wolverhampton Polytechnic, was appointed the deputy senior district judge in 2017 and is now ticketed to hear extradition and terrorism cases. Previously he was an associate judge of Her Majesty’s Court of Sovereign Base Areas in Cyprus. Ikram is the deputy lead Diversity and Community Relations judge, one of the editors of the Equal Treatment benchbook and a member of the Judiciary’s Diversity Committee. Most recently, he was made CBE commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire in 2022 for services to judicial diversity, and his deputy contenant for the Royal county of Berkshire.

Ikram agreed with the idea that overtly racist violence was not a problem relegated to America. He shared the case of Mark Duggan, a man of African-Caribbean descent who was shot by the Tottenham police in 2011. After his death, people protested in the streets in what is now called the London Riots in a similar manner to how people would protest years later for George Floyd.

“Black people are seven times more likely to be stopped and searched than white people. They’re five times more likely to be subjected to the use of force [by police],” he pointed out as an example of racial bias in the police force.

Moreover, he added, “When you speak to people from various communities, they say: ‘We find the police confrontational. They stigmatize our community, and they humiliate us.’ The majority of people in England and Wales who come from ethnic minority backgrounds do not trust us in the criminal justice system.”

That is the problem, and consequence, of unfair police practices. There is no confidence in the police.

Ikram measured the issue in numbers, stating, “The average confidence level in the police is 74% in the UK. But that drops to 54% in relation to people of Black and Caribbean heritage,” he continued.“Black people figure 60 arrests per 1000. White people are only 17. If you’re a Black man, you’re more likely to be killed; you’re more likely to be the victim of crime. On top of that, 1.5% of police officers in England and Wales are Black. It’s an incredibly low figure.”

Besides statistics, he shared with the audience a case he witnessed as a judge of racism within the police force.

“I sent somebody to prison recently. It was a police officer. He was on a Whatsapp group and was sending messages to all his fellow police officers, which were disgustingly racist. And he said it was a private group,” he explained. “This was a police officer bringing the police service into disrepute. So I gave him a long prison sentence. The police were horrified by that. Because it was the first time that a police officer had been sent down in those sorts of circumstances.”

Culture is difficult to change in organizations, particularly in such an entrenched institution like the police. Ikram argued how this must change.

“So if you have an outcome, a statistical outcome, which is troublesome,” Ikram said. “For example: Why are people who are Black more likely to be killed or to be stopped and more likely to be searched? And you can’t give a non-discriminatory, non-racist explanation of why that is the case, then you have a problem. If you can’t explain it, you’re gonna have to reform it.”

The judge expanded on how, at least in the UK, the police are working to solve this issue. He included some failed attempts of this process, too.

“The police decided to introduce a new filter software. And it was called the Gang Matrix. They were going to keep data on lots and lots of people who they perceived to be members of a gang or likely to commit violence. Well, what’d you know, 78% of those names ended up to be Black males.”

Ikram built on how after further investigation from the mayor of London, several names were removed from the database, even though the Matrix hasn’t been completely terminated.

“I’ve always said it; I’ll say it again: putting things on pieces of paper makes no difference. Policies are absolutely worthless until they are converted into action. Policies are not enough.”

He also discusses how judges, like him, could be suffering from unconscious bias when sentencing people. In fact, part of training for a judge expects to remove that same bias. Ikram explains he was among a number of judges who authored a document called the Equal Treatment Bench Book. This book seeks to eliminate unfair judicial practices by increasing awareness and understanding of the different circumstances of people in court. Ikram was involved in reviewing a chapter on cultural and ethnic differences. This is just one step in the right direction.

“We deal with issues such as discrimination. We can’t skirt around that issue. Because it’s out there.” he stated.

Before he left, Ikram opened the floor for questions. He answered a student’s question regarding Illinois’ recent elimination of cash bail with the passing of the SAFE-T Act.

He said, “I suspect issues like bail bonds discriminate against people from different communities. And you are actually institutionalizing embedded racism. Not overtly, you’re not intentionally being racist. But there are consequences of that.

“Otherwise, what you’re really doing is saying if you’re rich, you can buy yourself better,” Ikram continued. “And if you happen to come from a poor family, you’re in trouble. That’s not right. That’s exactly what breeds lack of confidence in the system.”

Ikram concluded the talk by addressing the audience.

“There are real issues of confidence in people who are wondering whether criminal justice really works. That means we’ve still got a lot of work to do.”