Popular free college programs yield mixed results

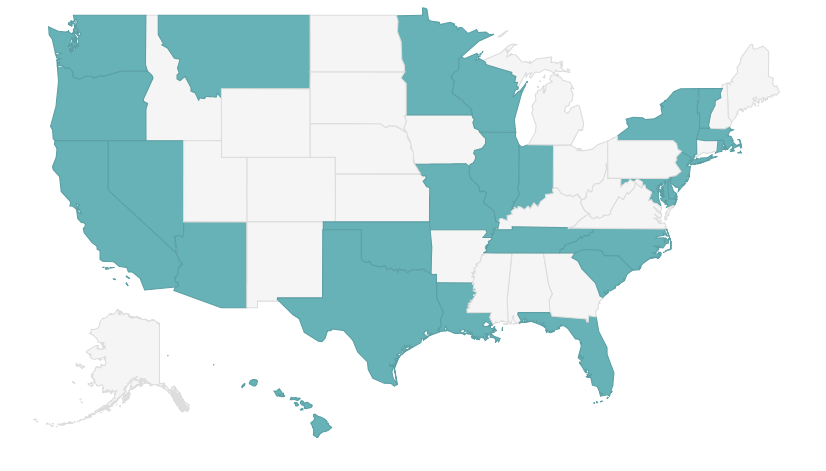

Blue states are either operating a free tuition program or proposing to start one.

October 2, 2018

“Free college” is an increasingly popular idea to help students afford higher education. Sen. Bernie Sanders made it a centerpiece of his 2016 presidential campaign. But well before then, cities — usually using private, philanthropic funding — had been experimenting with innovative programs to boost college graduation rates by promising to pay tuition for students who study hard in high school.

One of the earliest and most well-known is the Kalamazoo Promise, a scholarship created in 2005, which pays all tuition and fees for graduates of the city’s public high schools to attend any public two- or four-year college in the state of Michigan. That blueprint slowly caught on and then rapidly spread in the last five years. One University of Pennsylvania study published in April 2018 counted 289 similar programs around the country as of November 2016, many of them newly established in 2016.

Now many states, including New York and Tennessee, are offering their own versions of free college tuition to high school students. Fifteen states currently operate some version of a free tuition program, according to a September 2018 count by The Education Trust, a nonprofit group that conducts research and advocates for low-income students. Another 11 states are considering proposals to enact them.

Details vary in both the local and statewide programs. Some cover all tuition and fees; others don’t. Some just cover two-year community colleges, others four-year institutions as well. Some only give assistance to low-income students, others only to students who meet certain academic thresholds and others to a combination of those with need and merit. The rules for dispensing the scholarship money can be controversial. Many programs require students to exhaust other forms of aid first, such as Federal Pell grants and state aid, which are often large enough to cover community college tuition for low-income students. That means many low-income students might not receive any extra money from these “last dollar” rules, as they are called.

Some programs have been around long enough that there’s a track record to study. One analysis of 32 “promise” programs, which give tuition assistance for two-year colleges, found that new enrollments at colleges where the students were allowed to use the financial aid increased by 9 to 22 percent. But the researchers, Amy Li at the University of Northern Colorado and Denisa Gándara at Southern Methodist University, who presented their findings in September 2018, didn’t have data yet on whether more students were earning diplomas.

Another September 2018 study from the Brookings Institution looked at graduation data in Milwaukee, which introduced a free tuition program for some public school students in 2011. Half the 36 high schools in the city were randomly assigned to offer scholarships of up to $12,000 for students who maintained at least C-plus/B-minus average in high school and graduated on time. That’s enough money cover all tuition and fees at the local two-year college. The funds could also be used to attend four-year colleges, covering more than one year of tuition and fees. In comparing the outcomes of students who had the opportunity to get this scholarship with those who didn’t, the researchers found no difference in high school grades and whether they went to college straight after high school. They found slightly higher graduation rates at two-year colleges but that doesn’t seem to be the case at four-year colleges. More three years after high school graduation, the Milwaukee scholarship students aren’t attending four-year colleges in great enough numbers to increase the number of bachelor’s degrees.

“It seems clear at this point that many of the potential benefits, during and just after high school, did not emerge,” wrote the authors, led by economist Douglas Harris of Tulane University.

Harris and his team recommend getting rid of performance requirements, such as maintaining a certain high school grade point average. They found no evidence that these requirements induce students to work harder and become more academically prepared for college. Instead, they have the unintended consequence of steering more funds to higher-income families, whose children are more likely to have higher grades.

The Education Trust is particularly concerned that many free tuition programs aren’t really helping low-income families because tuition is only 20 percent of a community college student’s annual budget.

“Students from low-income families attending community colleges can typically afford tuition with help of the Pell Grant, so they don’t benefit from statewide free college programs designed to cover only the cost of tuition,” wrote Katie Berger, a policy analyst at Ed Trust. “However, these students still cannot afford college because they struggle with non-tuition costs, such as books, housing, and transportation.”

To give meaningful help to low-income students, Ed Trust recommends that states should allow them to use this “tuition” aid for living expenses, and that states should cover tuition for four years of college, not just the first two. They also propose that low-income adults should be able to tap into this tuition aid to return to college, and not restrict it only to recent high school graduates or those who’ve never attempted college in the past.

Changing the rules of these free tuition programs to give low-income students four years of free college might be too expensive for many states to fund. But it’s increasingly clear that “free college,” as it is often currently implemented, may be more of a marketing message than a policy that will boost the education level of the future American workforce.

This story about free college was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.