Lessons from a Freedom Rider

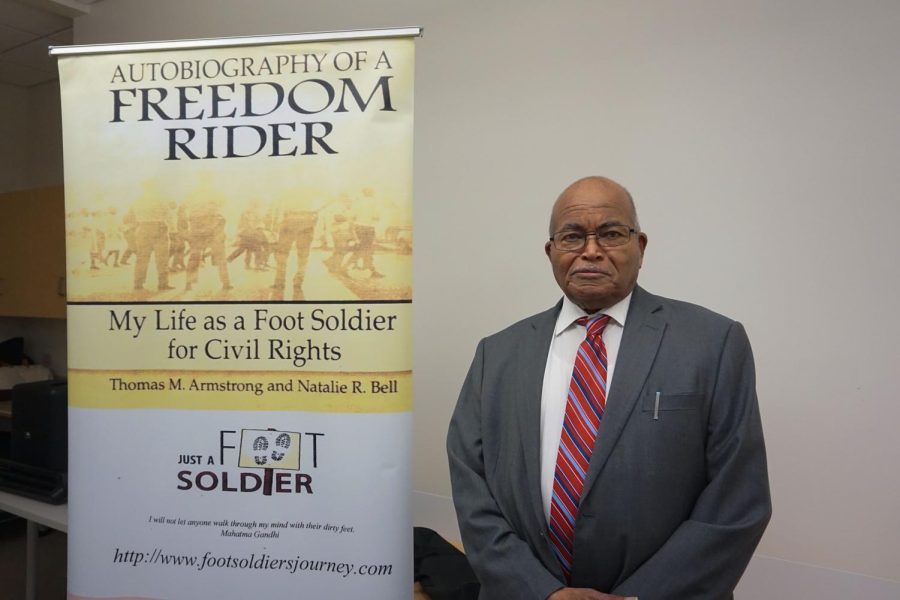

As part of COD’s Black History Month events, students and faculty alike had the honor to listen to Thomas Armstrong, a freedom rider and civil rights activist.

February 20, 2023

Thomas Armstrong was born and raised in Mississippi when racial segregation ran rampant throughout America. Currently, he is a civic education consultant who works with teachers and students to educate about the Civil Rights movement. But, before that, he was a Freedom Rider.

Last Thursday, he shared what being a Freedom Rider was all about with COD students.

Freedom Riders were Civil Rights activists who, during the 1960s, protested against racial segregation in bus terminals by riding interstate buses through the South. For over 30 years, Armstrong did not speak publicly about his civil rights experience as a freedom rider. The inspiration to share his story came within his family.

He says, “One of the reasons that my experiences became public was my granddaughter Aleena.”

Armstrong explained that, after watching a documentary about the Civil Rights movement “Eyes on the Prize,” his granddaughter asked him about his involvement during that period. His other relatives wanted to know, too. He hadn’t told them yet. After opening up about his experience, his family encouraged him to write about it.

Before talking about his time as a Freedom Rider, Armstrong recounted how racism impacted his childhood.

“Every time I see an ice cream cone it makes me angry,” he said. “As a kid, before school, I asked for a cone at the ice cream parlor. The man asked me ‘Can’t you read, boy?’ pointing at a sign reading ‘white only.’ After denying me the ice cream, he instructed me to go around the side, where I found a garbage can swarming with flies. That was my first encounter with segregation in the state of Mississippi.”

This situation was the beginning in a long series of events where Armstrong faced racial injustice.

He recalled how, when he began involving himself in the movement, his safety was jeopardized.

“Someone was watching us, and that someone was the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission,” Armstong said. “It was created in 1956 and chaired by the governor of the state of Mississippi. At that particular time it was a spy agency.”

Armstrong clarified how the agency was funded by the opposition to the Civil Rights movement. They hired investigators and local informants to monitor and disrupt Civil Rights activities across the state.

“They kept surveillance files on all of us who they felt were involved in the Civil Rights movement and organizations,” he explained.

Years later, Armstrong found more than 20 documents that dealt with him and his Civil Rights activities in the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission’s files.

“As they were financed by the state, I would pay, through my taxes, for the Sovereignty Commission to spy on me,” he said.

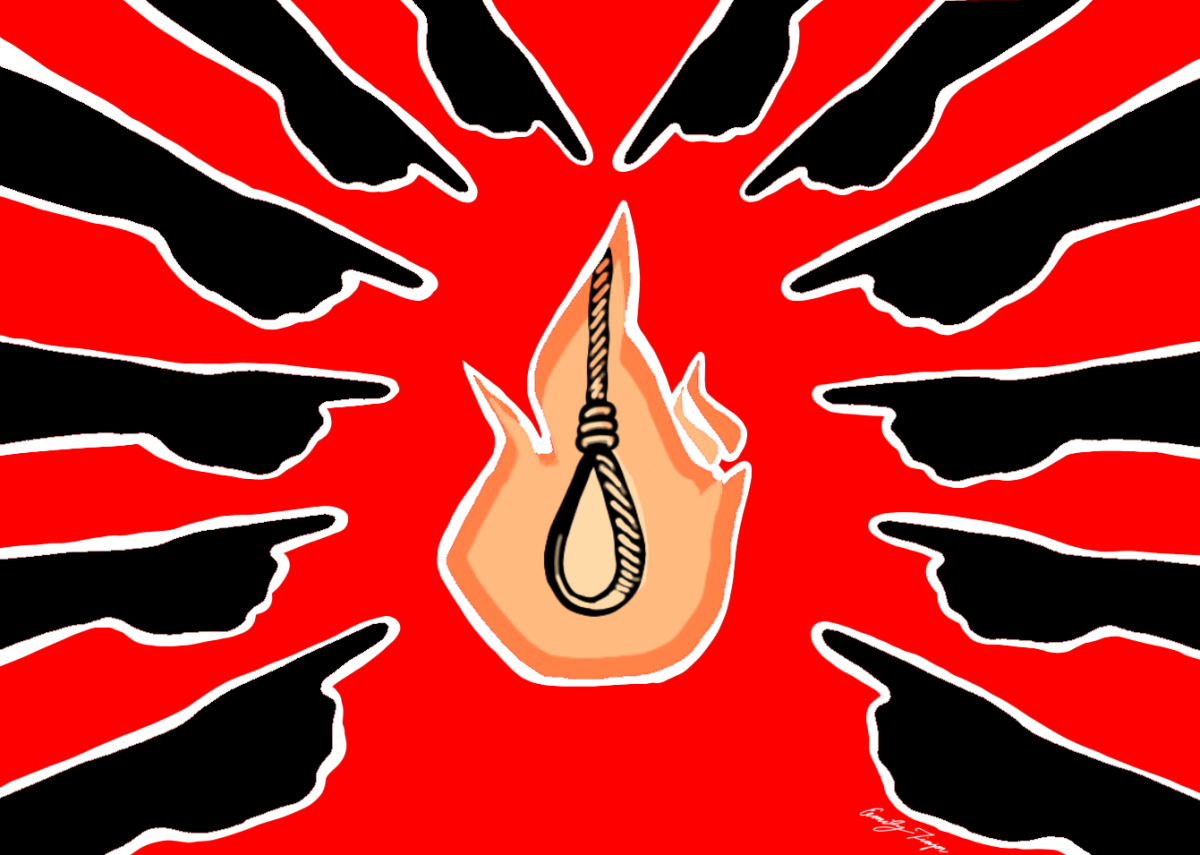

Besides being a target for organizations, there were many risks in being a Civil Rights activist. For instance, he recalled, sometimes buses were firebombed and police officers used brutal strategies such as dogs to attack protesters. Still, Armstrong was committed to the cause. His inspiration to join and perdure in the Civil Rights movement was his mentor, Medgar Evers.

“One of the many reasons for the successes of the movement was Medgar Evers. He was a Mississippi State field secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.” He continued, “He was the bravest man I ever knew. But on June 12, 1963 , he was shot and killed just days before his 38th birthday, because he wanted equality for Black people. That’s the reason he was killed.”

Armstrong claimed the story is oversimplified to but a few names, without accounting for the ‘little people,’ a term coined by Evers, who paved the way with small but potent contributions.

“Medgar called us the ‘little people against the system,’ and that we were the ones on the frontline of the cause,” Armstrong said. “We were ordinary foot soldiers of the movement. I’m almost sure that most of you have heard of Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks and Malcolm X, but there also were the little people.”

After his experiences, Armstrong highlighted the importance of learning about the hidden history of the movement. He posed the idea that books like his, detailing events of African-American history, be included in curriculum of all high schools and universities.

“History books should get their facts straight. There’s a movement now that wishes to ban books and especially history books that tell the true story of this great country. Sometimes our history books are not telling you all of the information.” he said, referring to the Florida movement to ban books and classes about African-American history.

Moreover, he encouraged us, college students, to use our right to vote.

“Some of you here are probably wondering to yourself: How can we really make a difference? What’s the point in voting? However, your single vote matters way more than you think.”

He expanded on the topic by explaining, “No longer will it be enough for you to use the ‘I Voted’ sticker. Now it becomes, who are you going to take to the polls with you. It’s difficult for me to find a way to express to you the sin

cerity of our plight: Too many people have died for your right to vote.

Armstrong said voting should be free and without restriction for all Americans. Moreover, he said it is un-American for anyone to place any restriction on the right to vote, and if they do, “they just don’t love America.”

Closing his speech, he referred to his work as a Freedom Rider, and left a message for the new generations.

“The old team has been expanded; you are the new team,” Armstrong told the audience. “Will you carry the torch? How will you run the race, and how will you continue the fight for truth and justice? We are the champions of our own souls. We can change things. Believe in yourself, and you can change the world. Peace is just around the corner.”