Is there a right end of the noose?

American injustice in the death penalty

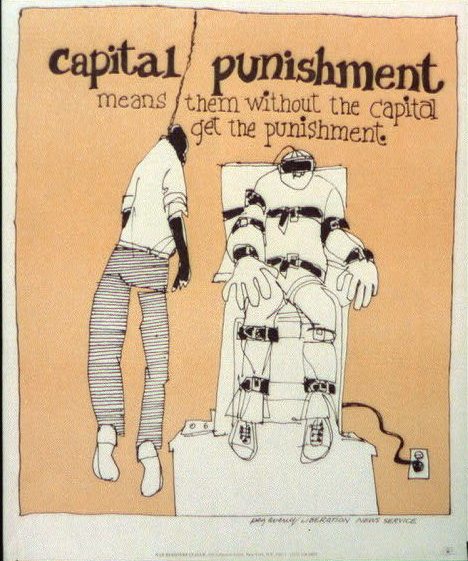

The argument goes, those who commit acts of violence should pay for their crimes. However, almost all people on death row are poor. A significant number are mentally disabled. And about 40% of death row inmates are African American

January 24, 2019

There is a difference between doing what is easy, and what is right.

It is easy to submit to revenge. It is easy to seek out retribution over upholding the ethics of justice.

The death penalty is a comfort Americans use to patch over dysfunctions of society they are most ashamed by.

Ending is better than mending.

The debate will once again stir in the death penalty appeal for convicted Boston Marathon bomber Dzokhar Tsarnaev.

If there is, as the saying goes, a wrong end of the noose, what does it say for those doling out the punishment? Can those letting fear govern justice evade corrupting their own authority?

Tsarnaev, 25, is one of the two convicted bombers of the 2013 Boston Marathon. Nineteen at the time of the attack, he, along with his older brother Tamerlan, used homemade pressure-cooker bombs to kill three people and wound more than 260 others. They also fatally shot a police officer while on the run from authorities. Tamerlan was killed while trying to evade capture.

While capital punishment has been abolished in Massachusetts since 1984, federal crimes committed in the state are still subject to the death penalty.

Tsarnaev’s lawyers argued he was under the influence of his radicalized older brother. They also argued by a lower-court judge refusing to move the case outside of Boston, the city’s traumatized public deprived Tsarnaev of a fair and impartial trial.

Are those engulfed in emotional turmoil capable of upholding judicial impartiality? Are the rights protected by the Constitution prone to subjectivity? The history of the death penalty in America is one of bias, discrimination and arbitrary sentencing. Upholding the Constitution has become subservient to the authoritarian justice sought by an emotional public’s ulterior motives.

Capital punishment is currently legal in 30 states (not including Illinois), although 13 of those states have abandoned the practice.

The American Civil Liberties Union has long been fighting for nation-wide abolition of the death penalty.

They have publicly stated, “Capital punishment is an intolerable denial of civil liberties and is inconsistent with the fundamental values of our democratic system.”

They believe capital punishment deceives the public of a false governmental protection and fails as a deterrent against violent crime and homicide.

Adherents arguing those who commit crimes should pay for what they’ve done, fail to see the extreme arbitrary discrimination in sentencing.

The ACLU highlights almost all those on death row are poor. A significant number are mentally disabled. And about 40% of death row inmates are African American.

Historic discrimination in executions brought capital punishment before the Supreme Court in 1972. Research from lawyer Donald Partington showed from 1908-1963, of the 41 people executed for rape and 13 for attempted rape, all were black even though 56% of those convicted were white.

Furman v. Georgia (1972) ruled capital punishment was being applied unconstitutionally in a discriminating fashion towards minorities and temporarily abolished the death penalty. After states amended their death penalty statues, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the legality of capital punishment in Gregg v. Georgia (1976).

Since 1976, 7,800 have been sentenced to death with 1,400 executed. 148 defendants were exonerated in their case before execution.

Capital punishment sentences have always been at the mercy of the judge’s explicit or subconscious biases and discriminations. The same impurities of morality have impeded even-handed jury decisions.

In 2018, of the 25 nationwide executions, 13 were in Texas. All the seven people Texas sentenced to death in 2018 were people of color.

Lack of uniformity and a subjection to capricious judgments have dominated nation-wide sentencing. A 2001 study from the Univ. of North Carolina found in North Carolina, the odds of receiving a death sentence were 3.5 times higher among defendants whose victims were white.

Race, gender, social class, and location of the crime supersede the federal constitution when dictating sentencing.

Three-quarters of those sentenced to death were poor enough to only be provided a legal-aid lawyer.

Of the 1,400 executed since 1976, Texas has executed 548, Virginia 113, and Oklahoma 112 people.

The supportive states argue capital punishment serves as a deterrent against violent crime. However, states without capital punishment have lower crime rates, and those with it average 50% higher homicide rates.

Deterrence works on the presumption of rational criminals acting upon premeditation. However, many violent crimes are instead committed upon impulse.

Capital punishment has become less about actual deterrence and more about those in power appeasing the masses to protect their monopoly on authority. The ruling-class uses the guise of security and false-justice to protect its own privileged position in society.

While most Western-democracies have abolished or abandoned the practice of capital punishment, America’s continuance has placed it alongside regimes in China, Iran, Saudi Arabia and North Korea.

Exercising authoritarian control over an individual preserves the status-quo maintaining the social hierarchy.

It is natural to want vengeance. However, our Constitution holds us to a higher reasoning. Fear amongst the public not only impinges upon the civil rights of defendants, but corrodes the public’s own constitutional protections.

Emotion cannot compromise the objective truths provided by the Constitution.

Nowhere does it dictate homicide forfeits your inalienable right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Nor does it say murder permits the public to take these rights from another American citizen.

Upholding the death sentence against Tsarnaev would violate the constitutional ban against cruel and unusual punishment provided by the Eighth Amendment.

The horrors of his crime do not excuse the lapse of our judicial ethics.

Discriminatory sentencing violates the due process of law and equal protection provided by the Fourteenth Amendment.

By arbitrarily forsaking the rule of law to appease a demand for justice, the United States forfeits their mandate to help end human rights violations and abuses of authority across the globe.

By sentencing Tsarnaev to death, we normalize violence and banalize acts of brutality in society.

There is an inherent hypocrisy of states in the name of justice committing the heinous act of taking another’s life. The rule of law cannot become circumstantial.

Amnesty International calls the death penalty a, “symptom of a culture of violence, not a solution to it.”

Amnesty believes capital punishment violates the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations in 1948.

106 nations have abolished the death penalty, with another 142 nations abolishing it in practice.

25 people were executed in America in 2018, continuing a downward trend from a peak of 98 executed in 1999. 40 more people were sentenced to death row compared to 315 in 1996. There are currently 2,817 people on death row.

Objectors point to the average wait time offenders experience of 10 years before execution as being an example of cruel and unusual punishment.

Because the judicial system will always be imperfect and vulnerable to bias, innocent lives have been executed before exoneration.

In 2018, Vincente Figueroa was exonerated in California after 26 years on death row, and Clemente Aguirre in Florida was released from prison after 12 years on death row.

Lengthy trials and appeals contribute to substantial costs for capital punishment cases in comparison to life-long imprisonment.

In a state review, Kansas concluded capital cases are 70% more expensive than non-death cases, including the costs of lifetime incarceration. Death penalty cases in North Carolina total $2.16 million more per case than life imprisonment. In Florida, costs total $51 million a year above what it would cost to punish all murderers with life in prison.

If states wanted to deter crime, they should expropriate those funds to education and social programs for the states’ poorest and highest crime neighborhoods.

Retribution has been prioritized above reforming maligned dysfunctions of society.

Ethics have become sacrificed under the false predicate family and friends of the victim will feel closure as the result of the killer’s death.

South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu has stated, “To take a life when a life has been lost is revenge, it is not justice.”

Hatred and revenge do not fill the bereaved with solace. More violence cannot mollify the burden of a loved one being taken from you.

Revenge is a disease spreading from person to person. Nowhere is justice had by taking another’s life.

Families and friends of the 2017 Charleston church shooting have shown only forgiveness will help with release.

Nowhere does the law state who is unworthy of rehabilitation and who is unjust of forgiveness.

In opposition to the death penalty given to Dylann Roof, 21, for killing nine churchgoers, family members of the victims appealed for mercy.

“You took something very precious from me. I will never talk to her ever again. I will never be able to hold her again, but I forgive you. And (may God) have mercy on your soul,” said the daughter of victim Ethel Lance.

Their actions of forgiveness were not enough to appease the jury’s demand for vengeance. Roof was sentenced to death by lethal injection.

When the needle pierces his vein, the world will not be made any safer, the families will not feel any closure, and society will once again turn a blind-eye to a barbaric act of unconstitutional injustice.