Is North Korea’s participation in the Olympics a positive step for diplomacy?

February 20, 2018

Precariously traversing a diplomatic duality, autocratic North Korean leader Kim Jong-un has extended an “olive branch” of reconciliation towards South Korea while simultaneously displaying the pomp of his military might. Triumphantly standing sentinel as synchronized soldiers, tanks and ballistic missiles parade past in his honour. Kim has ostentatiously moved up his regime’s April parade to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the Korean People’s Army to a day before the opening ceremony of the 2018 Winter Olympics hosted in Pyeongchang, South Korea.

In a shocking rapprochement, the North accepted South Korea’s amicable overtures and agreed to send a delegation to participate in the global festivities. In negotiations lasting only over a week, the two nations along with the International Olympic Committee (IOC) permitted 22 athletes from the North to compete.

In discussing the implications of hypocritically implying a desire for diplomacy yet holding a parade demonstrating their military might, College of DuPage political science professor David Goldberg underscores, “the more Kim starts from a position of strength, the more he is able to give without creating a perception of weakness or vulnerability.” This strength reinforces the domestic authority of Kim’s rule, and enables him to leverage his way into diplomatically seeking legitimacy for his regime.

Beneath the cacophonous flag, the North’s athletes traveled with a delegation of coaches, trainers, a vivacious cheer team and the potential geopolitically dynamic duo of ceremonial head of state Kim Yong-nam and sister of Kim Jong-un, the US blacklisted Kim Yo-jong. Yo-jong represents the first visit to the South by a member of the authoritative ruling family since the peninsula’s partition following cessation of the 1950-53 Korean War, to which a peace accord was never signed.

The sending of the head of state and Kim Jong-un’s sister signify a significant effort towards a détente with the South. This necessitation comes after a strikingly hostile 2017, in which North Korea conducted its 6th nuclear test and launched several ballistic missiles, striking fear into regional nations and drawing a heated and imbecilic rebuke from our Commander-in-chief. With fears North Korea’s arsenal can now reach mainland America, the urgency of diplomacy has never been more important.

In a symbolic gesture, both Korean nations marched under a single “unification flag” in the game’s opening ceremonies and had a citizen of each symbiotically deliver the Olympic torch to the cauldron igniter. The harmonious gestures continue with both nations playing with a unified women’s ice hockey team comprised of 12 North Koreans and 23 South Koreans, in the first ever combined team to be featured at an Olympic event.

Professor Goldberg iterates the games provide a platform for diplomacy, stating, “people tend to link the bond between sports and politics as superficial, but it presents an opportunity for real conversations to take place.” Utilizing this great opportunity, South Korea’s new audacious liberal President Moon Jae-in expressed a hope this Olympics would be remembered as the “day peace began”.

Echoing Moon’s sentiments during his new-years speech, Kim Jong-un expressed support for the games and a wish to “melt the frozen North-South relations”. This revelation foreshadowed the reopening of diplomatic channels between the two nations after a hostile two-year hiatus. In a calculated move, Kim’s actions as the apparent peacemaker play into the domestically fed narrative of North Korea being a victim of international aggression and intimidation. Kim wants to display to the world that despite international sanctions his nation is still powerful and thriving. However, skepticism over Kim’s intentions have been levied by those such as Japan’s Minister for Foreign Affairs Taro Kono, who inferred the North was utilizing the games as a platform to improve its image, while progressing its missile and nuclear programs surreptitiously.

In concordance, US Vice President Mike Pence accused North Korea of “using the games to paper over the truth about their regime.” He acknowledged the US would soon levy “the toughest and most aggressive round of economic sanctions on North Korea ever.” Hindering peaceful diplomacy, Pence has refused to meet North Korean officials (now paralleled by North Korea saying they have no intentions of meeting US officials) until they, “once and for all abandon their nuclear and ballistic missile ambition.” Pence has further stoked tensions by traveling with the father of Otto Warmbier, who died after being imprisoned in North Korea, and walking out of a diplomatic dinner organized by Moon Jae-in featuring Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and the North’s head of state.

Pushing Pence’s stubborn antics aside, Professor Goldberg theorizes the American reaction should be to, “work behind the scenes, talk to Beijing and Moscow, and talk to the UN Security Council about passing dialogue that goes in the right direction.” International cooperation must be required to pacify the peninsula.

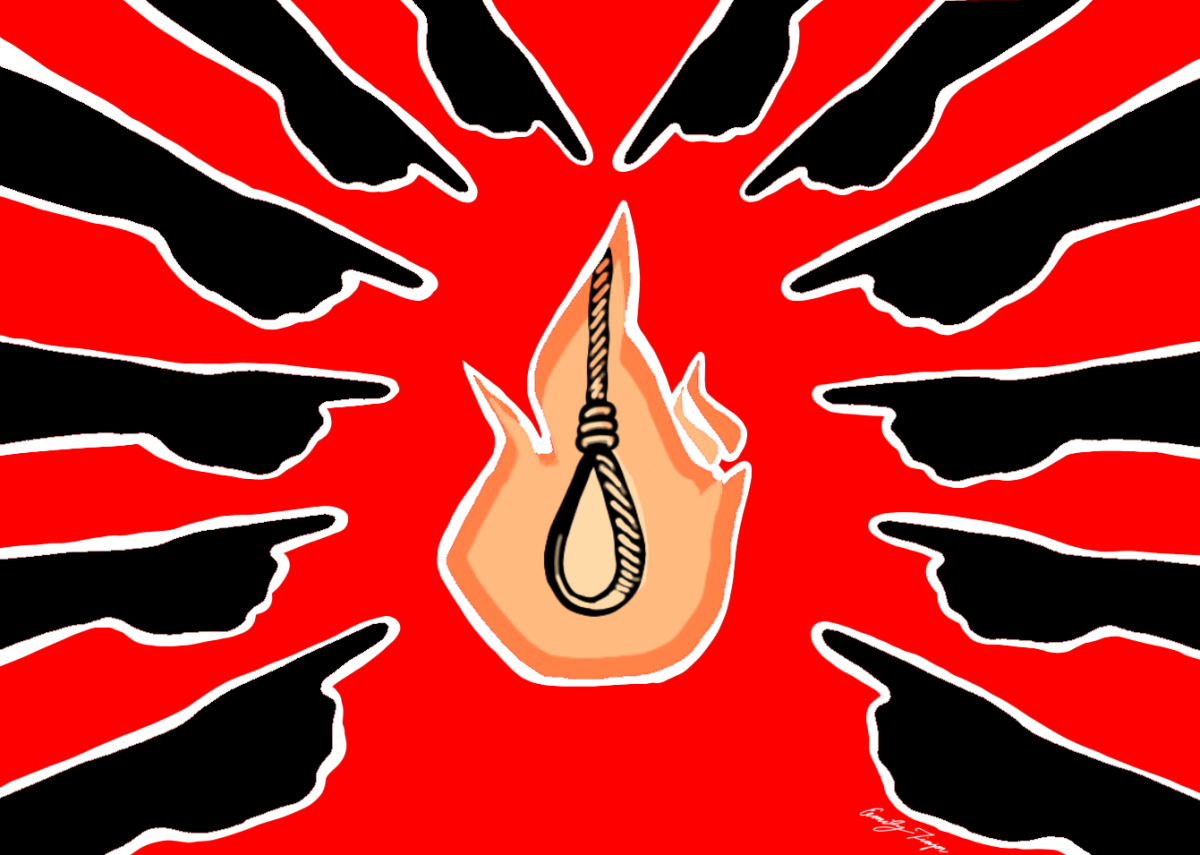

Exhibiting this cooperation, Moon’s liberal audacity in seeking the pacification of tensions can be seen as a divergence from past hostilities featuring international sporting events held in South Korea. North Korea boycotted both the 1986 Asian Games and the 1988 Olympics. As preparations commenced for the 1988 games, two North Korean agents planted a bomb on Korean Air Flight 858 detonating it over the Andaman Sea, killing all 115 people on board. Further aggressions transpired during the 2002 FIFA World Cup co-hosted by South Korea and Japan, when North Korean patrol boats opened fire on a South Korean naval ship who they perceived as crossing the maritime border separating the nations in the Yellow Sea, killing 6 South Koreans and severely injuring 9 more.

The potential for such violence or acts of terrorism significantly decreases with the North’s participation in the games. Evidential of tangible diplomatic repercussions, the 2014 Asian Games hosted in South Korea provided the foes a platform to reinitiate a program providing brief reunions for families torn asunder by the separated peninsula during the war. Such familial reunions have not taken place since 2015.

A significant step towards peace was taken when Kim Yo-jong presented a letter from her brother to President Moon with an invitation to partake in a diplomatic summit in the North, potentially the first summit in more than a decade between the two nations. Moon has expressed interest, but has demanded the North re-open dialogue with the US.

However, critics will point to the North’s resistance in abating their nuclear program, and the fact the Olympics provide a propaganda stage for Kim Jong-un to further construct a false narrative and feed it to his people. The games will be broadcast in the North, but they will be heavily censored for maximum political gain. The opening ceremony was not broadcast due to it depicting South Korea in a powerful and positive light. Instead the regime broadcasted patriotic songs and slogans celebrating industry and the armed forces. Given the North has only won two medals in the Winter Olympics (both in speed skating), the strength Kim is looking to display will be in his diplomatic skills while maintaining the leverage of his nuclear program.

Seeing the potential hypocrisy Professor Goldberg exclaims, “if it turns out this is all a subterfuge and Kim’s allowing these conversations to take place publicly while privately still ramping up nuclear capabilities, then that’s a problem for US policy.” However, Goldberg sees the will of the people on the peninsula and Korean public sentiment advocating for better relations catalyzing diplomacy between the two nations regardless of rhetorical sabre rattling.

Separated by only 50 miles from the most militarized border on the planet, the Pyeongchang games have already changed the dynamic in Korean diplomacy. The question remains, will these games be remembered as the “day peace began,” or will caustic hostilities once again destroy reconciliation for the Korean people?