Humanizing the faces behind the Syrian Civil War: Part I of II

April 26, 2018

This time the bombs looked different. A noxious gas released into the night air, choked, burned and suffocated any poor soul trapped in its pitiless sting.

As light broke on the April 7th attack in Eastern Ghouta, Syria, more than 40 people, mostly women and children, were found dead by a suspected chlorine attack launched by Syrian government forces.

The world reacted to a red-line being crossed. In retaliation for the suspected chemical weapons attack, President Trump, along with the UK and France, launched more than 100 missiles targeting Syrian government-controlled sites.

Some conservatives have celebrated the courage of Trump’s response to the Assad regime’s brutality. However, College of DuPage student Anas Abdulrazzak just sees more devastation for his fellow Syrians.

“The supposed red-line for chemical weapons is made up by outsiders. The civilians don’t care because we are dying anyways. Chemical weapons or being shot dead in the street, the brutality is still the same,” he said.

While the people of Syria have to survive senseless bombing after bombing, the American public is bombarded by numbers and daily acts of death and brutality on the news. The reports of widespread atrocities often become common-place. At first we feel sympathy for fellow human suffering, but insidiously creeps a growing apathy and indifference to the devastation. We shake our heads in disgust and perhaps support a tweet or like a post on social-media, but then continue on with our self-centered lives.

It becomes far too easy to see the numbers and gaze past the headlines, failing to acknowledge the human presence behind each bombing. We dehumanize their lives, failing to see the faces and the stories of those trapped by senseless violence.

We fail to see how the acts that appear a world away, in-fact affect each and every one of us.

Representing one of the stories and voices we fail to hear, is Anas Abdulrazzak. Abdulrazzak is a Syrian immigrant from the town of Hama, and is now an American collegiate aspiring for a dental major.

Abdulrazzak and his family escaped Syria in 2011, seven months after the revolution began. His siblings came to America while he finished his high school education in Saudi Arabia. Some cousins took shelter in Turkey, while others braved the Mediterranean migration route, which killed more than 3,100 people in 2017 alone, to reach the safe-haven of Germany.

It took many years after an application was filed to hear back for admission by the U.S. embassy. After 9/11, all Arab immigration was delayed. His grandmother applied for her daughter and her family’s admission in the 90’s, but didn’t hear back from the U.S. embassy until 2008. His family were admitted as immigrants and given green card status.

“And now, after Trump, it’s almost impossible to come as an immigrant. Even refugees are severely restricted,” said Abdulrazzak, who questions what was gained by the American bombing.

”I actually consider it a joke because it doesn’t really affect the war or change anything,” he said. “It’s all just for show. I wish Obama would have done it earlier in the conflict. It could have changed a lot. But now this far into the war, it makes no difference. Trump announced on Twitter days before the attack. So, in Syria, everyone moved everything out of the compounds.”

As a refugee, Abdulrazzak has lost more than just access to his homeland. He still has family in Hama, and Syrian culture makes up his identity. To shed a light on the society he left behind, Abdulrazzak explained how Syrian students are taught the same classes as in America.

“However, math is more difficult in Syria,” Abdulrazzak said. “Greater emphasis is placed on it than it is in America. We are required to learn English as a second language, and in middle school we also begin learning French.

Contrasting the two cultures, Abdulrazzak explained, “In America you get to choose your major. In Syria, the last year of high school you have a giant exam. Based on your score you are required to go into certain fields. You can only become something like a doctor if you get a very high score.”

To relieve the stress, students play video games and sports such as basketball, handball (similar to basketball and soccer combined) and soccer.

Syria has won three medals in the Summer Olympics (1 Gold, 1 Silver, 1 Bronze). Ghada Shouaa won the gold for the Women’s Heptathlon in the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta.

”Soccer is by far the most popular sport in Syria because it is the easiest and cheapest to play,” Abdulrazzak said. “I can remember it being played everywhere by children in the streets. My father says I was chasing a soccer ball around even before I knew how to walk.”

Professional soccer teams play in the Syrian Premier League, including his local team from Homs, Al-Karamah SC (8 total championships, second most successful team in league history). AL-Karamah was founded in 1928, and is considered one of Asia’s oldest sporting clubs.

The champion of the league plays in the Asian Champions League. In 2006, Al-Karamah lost by one goal to a South Korean team in the final.

The Syrian national soccer team has qualified for four Asian Cup competitions. They have never qualified for World Cup. However, in 2018 they reached the final round of qualifying, losing to Australia. Their biggest rival is Iraq, and political tensions often spill over into the sporting arena.

National sporting events such as soccer, or the olympics, simultaneously unite the public to cheer as one and aggravate the political divisions across society.

”Now with the war, especially with the success of the Syrian National Team in almost qualifying for the World Cup, it created a massive conversation amongst the Syrians,” Abdulrazzak said. “Should we cheer for the team or not? “Some people say we should because sports are separate from politics and the team represents our united people as a whole. However, during the national anthem the players are saluting, giving allegiance to the regime, praising the army who is destroying the whole country. In interviews after the game, the players are always quick to give thanks to (Syrian President Bashar) Assad. Therefore, I have trouble supporting the national team right now.

When the revolution began, athletes split, supporting different sides of the conflict. The goalie of a team in Homs actively supported the revolution, and a bounty was put on his head.”

Syrian superstar Omar Al-Somah has scored 130 goals in 118 games playing in the Saudi Professional League. He is the face for the brand ADIDAS, and if you go down any Saudi street you will see his face on advertisements. He did not play for four years leading up to 2017 for the national team, sitting out for political reasons. When the revolution began, he supported the rebels and raised money for hospitals in rebel-controlled land. Under suspicious circumstances, he came back and pledged allegiance to Assad enabling him to play for the national team.

Such political divisions are commonplace since the revolution began. However, Syria has always been a melting pot of people and cultural traditions.

”Syrian is Muslim majority, but we still recognize the Christian minority holidays,” Abdulrazzak said. “We constantly get days off to celebrate, such as during the Christian Christmas or Islamic Eid festival.”

Gathering for giant family holidays is what he misses most about Syria. After breaking their fast during Eid, they eat traditional foods such as Kubbeh, a mixture of wheat grain and minced lamb. It can be grilled, fried or baked.

“My favourite is Kubbeh over the grill; you bite into it, and it has onion and pomegranate. It’s a little spicy but very delicious,” said Abdulrazzak.

He continued, “In Syria, the social life is structured differently. In America, you go to work, come home, eat and sleep, and have most of your fun on the weekends. In Syria, you come home from work, sleep for an hour or so, and go out and enjoy a fun social night. Everyday is a full social day.”

However, maintaining a social life through social media has proven difficult.

Facebook was prohibited by the regime to control people’s communication. “When the revolution started, citizens started using a social media platform called Proxy, which fakes the user’s location. People were able to access Facebook and Twitter using Proxy undetected by authorities,” said Abdulrazzak.

Social media is important because there are only three large newspapers, and all are controlled by the regime, spreading propaganda. The channels and television news networks are the same way.

“However, non-state-run channels such as Arabic CNN and al Jazeera often slip into Syria. The government failed to suppress them, and they have given the public uncompromised news,” said Abdulrazzak.

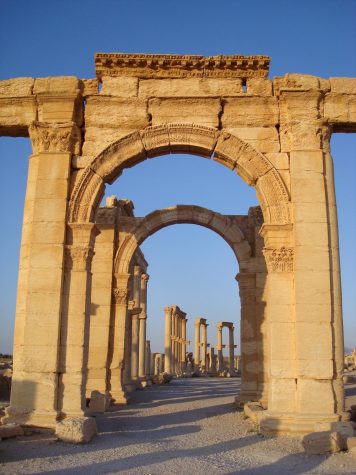

“Damascus is the oldest capital in the world, and some of Syria’s cities are among the oldest, most cultured in the world. We have beautiful castles, ancient architecture and Roman ruins. But nobody sees that. When they hear Syria, they just think of the war,” said Abdulrazzak. “We are a generous community, kind to each other. We are also a very proud people concerned with dignity.”

* When we gloss over the human side of conflict, we lose sight of the total devastation the violence has taken. What we lose can never be regained. We must ensure their voices are always heard.

* In Part II, Abdulrazzak will give a Syrian perspective of the Assad regime and where he sees the war leading