While facing unprecedented mass extinctions, Trump proposes weakening Endangered Species Act

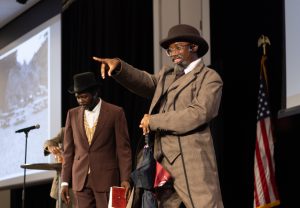

The Nachusa Grasslands in northwestern Illinois is one of the few remaining examples of the once-dominant tallgrass prairie ecosystem in the state. The Nature Conservancy reintroduced bison, natural grasses and wildflowers to the prairie (photo: Joey Weslo)

October 2, 2019

(9/25) On Friday, millions of students worldwide walked out of their classrooms demanding world leaders stop destroying the planet they will someday inherit. One of the largest ever youth-led demonstrations included thousands who gathered in Chicago to join the call to fight climate change

Teenage climate activist Greta Thunberg said at the United Nations Climate Action Summit on Monday, “People are dying and dying ecosystems are collapsing. We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is the money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth.”

But beyond reducing carbon emissions, what does this fight look like? Where are the political front lines on the battle for environmental protection?

The Trump Administration has proposed changes to the Endangered Species Act (1973) enabling the consideration of economic costs when deciding which species to provide protection. The proposal also removes blanket protections for newly listed “threatened” species, and allows the government to disregard the possible impacts of climate change when designating critical habitat necessary for recovery efforts.

The Washington Post reported Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross saying the proposal, “(fits) squarely within the president’s mandate of easing the regulatory burden on the American public without sacrificing our species’ protection and recovery goal.” The administration has previously rolled back regulations on methane emissions, car emissions and fuel efficiency standards, and regulations designed by former President Barack Obama’s administration to ensure clean air and water.

Since its signing, the act has helped species like the bald eagle, humpback whale, california condor, grizzly bear and the gray wolf rebound from dangerously low population levels. The act currently protects and provides recovery plans for over 1,600 endangered and threatened species. The bald eagle’s famous recovery plan involved banning the use of the pesticide DDT which caused their eggs to become brittle. Chicks were reared in incubators and fed with eagle-puppet gloves before being released into the wild.

Shamili Ajgaonkar, professor of biology at the College of DuPage believes such changes to the act would prove devastating for protecting biodiversity.

“The United Nations said in the face of climate change they expect a million species to go extinct,” said Ajgaonkar. “That’s an unprecedented rate of species loss. We have to stand up and pay attention. We need to intervene before these losses happen.”

Ajgaonkar has taken students to Alaska and Glacier National Park in Montana to study grizzly bears. She has also taken field study classes to Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming and Isle Royale National Park in Michigan to study Gray Wolves. Students explored the habits while learning about the dynamics and relationships between species in the ecosystems.

The Center for Biological Diversity has pointed to the loss of habitat as one of the reasons species are currently going extinct at 1,000 times the natural rate.

The Endangered Species Act has long been seen as a contentious political battle between conservationists and private landowners and industries. Infamous lawsuits have included the pitting of the logging industry in the northwest against the Spotted Owl, dam constructors against the Snail Darter Fish, and oil drillers against the Sage Grouse.

Ajgaonkar believes criticism of the law protecting a single species over industry represents a fundamental misunderstanding of the legislation. She believes flagship species symbolize something the public can rally behind when the true intention is protecting the health of the threatened ecosystem as a whole.

“Focusing on a specific species proposes challenges and false dichotomy,” said Ajgaonkar. “It puts the Spotted Owl against a logger’s job, or the Sage Grouse versus cheap oil. However, the Spotted Owl is an indicator species for old growth forests. If their population is healthy, the old growth forest ecosystem should be healthy. If the Sage Grouse declines, the entire ecosystem will be affected. It’s difficult to explain to the public the ecosystems approach to conservation.”

Ajgaonkar said biodiversity can be protected at three levels. Genetic biodiversity ensures a species can adapt to changing environmental conditions through its offspring. Species biodiversity represents how many species are being preserved. Ecological biodiversity involves protecting and maintaining the entire ecosystem. A recovery plan is developed for a charismatic or keystone species with the assumption its recovery will signify the recovery of the entire ecosystem.

College of DuPage currently dedicates over 45 of its 273 acres to natural habitat, including a structurally restored prairie.

Elizabeth Bach is an ecosystem restoration scientist with the Nature Conservancy. She works at the Nachusa Grasslands in northwest Illinois. The non-profit has worked to restore the natural tallgrass prairie that was once the dominant ecosystem in Illinois. Bach said less than one-tenth of 1% of this ecosystem remains in the state. Worldwide, 96% has been lost to converted land use, making tallgrass prairie far more endangered than rain forest habitat. The removal of grassland is a direct contributor to the loss of over three billion birds in the U.S. and Canada since 1970, according to the academic journal Science.

Nachusa’s conversion from individual farmsteads to connected grassland included the seeding of traditional prairie grasses and the reintroduction of bison from South Dakota.

“We have several species at Nachusa we monitor and are concerned about, but we follow an ecosystem approach to conservation,” said Bach. “It’s the habitat and the interaction amongst many species that indicates health. We look at putting all the pieces of the habitat back together so the natural processes can take over.”

Bach said the discovery of the endangered Rusty-patched Bumblebee, the Prairie Bush Clover and the Eastern Prairie Fringed Orchid are all indications their efforts to restore the entire ecosystem are working.

“We don’t have the laws to protect the wider habitat, so it becomes an all-or-nothing fight over a single species,” said Bach. “The Endangered Species Act is the most powerful legal tool to protect land development and management. All living things have an intrinsic value, whether people, plants, or animals. In our society, it’s crucial to talk about the resources and services ecosystems provide beyond the economic value of a single species.”

Bach said some communities favor environmental rollbacks because they struggle with their livelihoods and employment. However, she pointed to the Sage Grouse as a positive example of mutualism between providing opportunities for ranchers while maintaining habitat for the species.

“We can improve habitat for biodiversity while also helping communities live off their resources in a sustainable manner,” said Bach. “If we can learn to work with nature, it alleviates a lot of conflict stemming from protecting an endangered or threatened species.”

Ajgaonkar believes when providing opportunity for all parties, short-term societal benefits should be contrasted against long-term repercussions.

“There’s the question of what the obligation of a private land owner is for the greater good of society and the environment,” said Ajgaonkar. “How does the short-term benefits of oil drilling compare to the destruction of an ecosystem? It’s not either the environment or your job; we all have to live on this planet. These are complex problems with multiple stakeholders. Every solution comes with a trade-off. We need to prioritize our values. Science only provides the data; ultimately the choices of how to act upon that evidence are shaped by society.”

Ajgaonkar said any impactful conservation legislation must take the effects of climate change into account. The necessity of regulation signifies there has already been a failure within society. The Trump administration argues climate change projections are over-dramatic and too much land is reserved for conservation.

“It’s worrisome to see so much of a lack of respect for science and the lack of use of evidence to shape policy,” said Ajgaonkar. “If we don’t have a provision in the Endangered Species Act to list a species based on climate change causing extinction, then we need to change the act. People often resist because they view the act as a way to regulate fossil fuels. This is a false duality. As a society we need to decide what type of future we want for our planet.”

Bach said climate change will affect both already-threatened habitats and people. Illinois is projected to get warmer and wetter. This will result in increased flooding, which can both damage the stability of ecosystems and negatively impacting peoples’ homes and farmers’ crops.

She believes activism on the local level can make a drastic impact. Often zoning boards decide how land management should be handled.

For example, in Romeoville there is debate over Hanson Material Quarry expanding their stone mining area into the rare wet-dolomite prairie ecosystem. The company wants to transplant the soil and plants to another site. Bach said while transplanting can work, it’s crucial to protect remnant habitats.

“Many plants require very specific soil conditions,” said Bach. “Also, animals have strong honing systems and will often return to the original habitat even if it’s been destroyed. It’s much easier to expand like we did here than to translocate a habitat.”

Bach points to the conservation successes at Nachusa as providing an example for local activism. She said the passion of younger activists like those who walked out of their classrooms for the climate change strike keeps her optimistic. She suggests people read past news headlines and read multiple sources to develop a more complex perspective on environmental issues. Listening to diverse opinions helps us understand where people are coming from.

“Politics is a powerful sphere, but there are lots of local efforts outside that sphere,” said Bach. “The quickest way to get to no hope is by thinking you as an individual can save the world. However, what are the couple of pieces we each can make a difference in? It will take all these smaller efforts to make a bigger change. Get out and experience natural areas around you. Find the thing that sparks your interest. Now, more than ever, we need people to speak out on all fronts to protect our ecosystems.”