The Monster Movie: What Does Your Favorite Say About You?

May 1, 2018

If you want to know what the world is afraid of, you only need look to what threatens it in the most recent monster movie. Maybe it’s science or government overreach, or perhaps it’s intrusion of privacy, or technology gone too far. Maybe it’s evolution, or space exploration, terrorism or climate change. Perhaps it is the idea that there is something out there smarter than us or bigger than us.

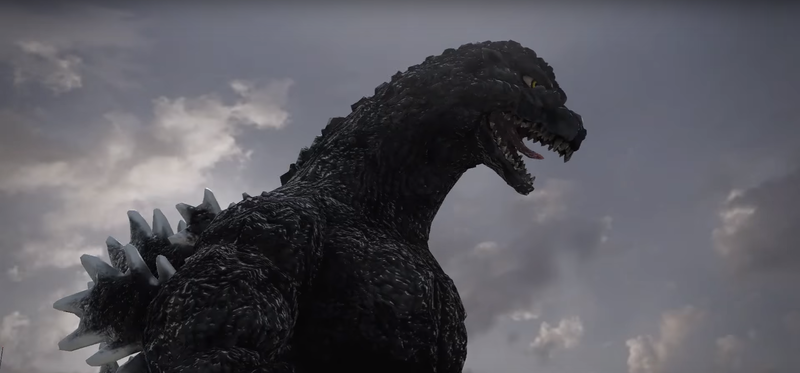

No matter what it is, who created it, where it came from or what it destroys, the monster will always be a recurrent character we will never tire of. Monsters in film depict the most pervasive threat of the day. The threat of nuclear radiation shown in the original “Godzilla,” became the threat of climate change portrayed in the 2014 remake. “Cloverfield” was a response to the threat of terrorism, just as “District 9” responded to apartheid. Countless monster movies have been made, and remade, to reflect the evolution of our collective fear.

“Monsters are about manifesting our cultural anxieties on screen. They are ways for us to play out the worst case scenarios that we can envision,” said Brian Brems, an English professor at College of DuPage who primarily teaches film classes.

With “A Quiet Place” receiving rave reviews, the recent releases of “Rampage” and “Pacific Rim: Uprising,” and another Godzilla film to look forward to in 2019, I decided to review two of my favorite monster movies. In doing so, I found what I might secretly fear the most.

The Host (2006)

If you can ignore some choppy acting and the awkward exposition during the initial scenes, “The Host” is a must-see. Written and directed by Bong Joon-Ho, who also wrote and directed “Okja” and “Snowpiercer,” “The Host” tells the story of a South Korean family and their fight to rescue the youngest member from a monster attacking Seoul.

This family was a wreck prior to the the attack. Incompetence, failure and self-destruction kept the three main siblings from the lives they had hoped for. The theme of incompetence is consistent, as the monster itself arose as a result of human laziness and irresponsibility. Both the South Korean and American government fail to come up with solutions. They can neither capture the monster, nor figure out where it came from or what it is. This reflects a common trope we also see in films like the recently released “Rampage” with Dwayne Johnson.

“The military and the U.S. government and science and the corporations are portrayed as not really understanding in depth the thing that they’ve created, and Johnson is really the only one who does,” Brems explained.

This is a common idea in monster movies. It is a reflection of our distrust in a faceless authority or government, and our desire to instill value and hope in one, mystically capable, man.

“A lot of American movies are built around the concept of a competent, usually white, male hero who is going to save the day,” Brems continued.

That is not what we see in the Host. There is no hero. There is no plan. There is a family of less than average individuals who have nothing but emotional willpower driving them to sacrifice what little they have to save a loved one. The film, in typical fashion for a South Korean production, does little to aid the family on their quest. However, the comedic nature of the film more than makes up for the lack of action-packed heroic deeds as the characters bungle and trip their way through their mission.

‘The Host can also be compared to “A Quiet Place,” with the real story being about a family rather than about a monster. In “A Quiet Place,” grief and loss bring a family together and reveals its strength. In “The Host” we are shown the capacity for grief and loss to drive people apart. The youngest member of the family, Hyun-Seo, is the glue that holds the family together. Her kidnapping by the monster is a reason for them to unite, but without her it is clear there is nothing else holding them together. While hope was able to unify them, grief and loss was an experience they couldn’t share. South Korean films are known for their brutal portrayal of authentic human experience. This film is no different. Hollywood films seem more likely to give you what you want to see, rather than what’s real.

“[Some films aren’t] designed to reflect the experiences of the audience but instead to provide them with the ideal,” Brems said. “American films tend to re-inscribe the values of the culture rather than break them down.”

“The Host” is not afraid to let its characters disappoint you. With human failure being the source of the monster’s creation, bureaucratic ineptitude being a part of its continued survival, and imperfect characters desperately trying to bring it down, incompetence is amplified. Monster movies are designed to ask the question: Would we be able to muster the collective action to fight this off? “The Host” presents an honest picture of how an ineffective and poorly planned human response to attack might be more realistic than we might want to believe.

“It’s more about breakdown than overcoming breakdown,…which is ultimately a less inspirational narrative,” Brems said.

Perhaps, though, it is more true to life.

Colossal (2016)

The manipulative abuser, who controls through degradation, versus the self-abuser who hurts others by hurting herself. Both are seemingly unaware or not seeming to care about the destruction their behavior leaves in its wake. Consumed by their own pain and suffering, they are blind to the way their actions affect others. Just like the monster who tramples across Seoul, obliviously crushing anything and everything in its path.

The metaphor is brilliant, as is the movie. “Colossal” is my favorite monster movie to date, and I love it more with every viewing.

Jason Sudeikis plays Oscar, a manipulative charmer who entraps the audience with his apparent good intentions, just as he entraps Gloria, played by Anne Hathaway.

“You’re sort of taken in, like she is, by his initial charm and welcoming. As she starts to move away from him and his psychological trouble becomes more apparent, then it’s already too late. You’re already invested in this relationship, as she is,” Brems explained. “She’s a prisoner of it just as you are.”

Gloria’s own self-abuse leaves her vulnerable to this kind of relationship, although Gloria is not innocent either. Her own behavior has allowed her to hurt people she supposedly cares about. The monster inside her is just as destructive. The question is: Will she be able to control it quickly enough to save herself, and Seoul, South Korea in the process.

What “Colossal” does so well is present a vivid picture of what the monsters inside us really look like, and what they can do to others. Alcoholism, addiction, self-abuse and relationship abuse. These issues are explored and then manifested into giant creatures that terrorize Seoul. The South Korean people are the collateral damage as Gloria learns an important lesson – her behavior has consequences outside of her own destruction. This realization helps her shake out of her downward spiral, motivating her to try and fix the damage she caused.

Another inept and unprepared hero, Gloria first must tackle her own monstrosity. To save others she must save herself. As she learns to control her monster, we see her tackling her alcoholism. Oscar’s monster’s only strength is his ability to manipulate others. The more control she takes of her own life, the less power he has.

The monster controlled by Gloria also represents cyber abuse. Initially comical, Gloria almost laughs about this newfound ability to manipulate the lives of others, in a devastating way, on the other side of the world. Online bullying, that seems so innocuous from behind our screens, is able to hurt and control others we may not even know or see. Real-world monsters, or “trolls”, are literally illustrated in “Colossal.”

“It speaks a lot to how we as human beings experience the modern world, which is vicarious relationship to tragedy. Tragedy happens all the time, but it’s mediated through our devices, the screens in our pocket,” Brems said. “There’s only so much that humans can engage through these devices. In Colossal, so much of it is about sitting and watching it through news of the destruction, and feeling disconnected to it, while at the same time as being the cause of it.”

Juxtapose this with the documentary style viewpoint shown in “Cloverfield,” a film that showed the horror New York experienced on 9/11. It portrayed the invasive reality of terrorism on American soil. The hand-held camera visually thrust us into that moment, which enhanced the horror. In “Colossal” the threat is once again at a distance. Just like the wars we see through our screens. In both movies, a monster destroys a city. In Colossal, the characters are able to almost forget this is happening to real people, even though they are responsible and could stop it.

“Both Cloverfield and Colossal would pair as a double feature. Taken together, they reflect two of the interconnected ways that we respond to tragedy now, which is either totally immersed in it if you are a participant or a victim… or a distanced relationship to it,” Brems explained. “Both are about how we, in the modern era, would respond to large-scale tragedy.”

When it comes to monster movies we are spoiled for choice. As long as there is something out there to be afraid of, film-makers will find a way to manifest that threat on screen. The upcoming monster blockbusters, while hopefully entertaining, may also end up being eye-opening – as long as we aren’t too busy hiding under the covers.