The Korean Club (Seoul of COD) discusses Olympics’ impact on tensions

March 12, 2018

Capitulating to a more amicable diplomatic position, U.S. Vice President Mike Pence transitioned from his hard-line isolation policy against nuclear-ambitioned North Korea to being open to diplomatic meetings and dialogue without any preconditioned stipulations. Bemused by the zeitgeist of the 2018 Winter Olympics in PyeongChang, South Korea, labeled by South Korean President Moon Jae-in as “the day peace began,” Pence’s evolution represents the cross-cultural power in sports transcending politics.

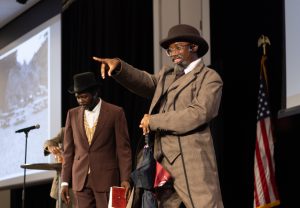

Discussing political ramifications and exploring the unique and fascinating Korean culture, the Korean Club (Seoul of College of DuPage) congregates to immerse themselves in the depths of Korean perspectives, language and its flourishing culture.

At their latest meeting, the repercussions and obstacles to a united Korean peninsula were discussed, and the difficulties in bringing people of disparate mindsets together. By participating in a fun debate activity we humanized the immovable opinions of both the citizens of North and South Korea, and illustrated just how difficult it is to come together when contrasting ideologies have been solidified.

The first step in breaking down cultural misunderstandings is to gain a sympathetic perspective. To further gain insight into Korean culture I sat down with Korean Club President Cheyenne Johnson and member Lollia Hamel to elaborate on the club’s perspective.

In addressing whether the Olympics has created a platform for peace or just serves as a propaganda tool for the North’s regime, Johnson begins how she perceives, “The Olympics provide great publicity for both countries and it does bring people together. However, this isn’t the first time they have come together for an international sporting event.” She continues, “They are almost like two feuding siblings in the same family. There is a shared familial history, but they are both certainly separate nations. I hope the Olympics bring a more peaceful communication between the two countries, but unless something major diplomatically happens, they are just going to stay in the uneasy parallel of separate countries who might not necessarily interfere with each other on a political level, but still have a shared regional and cultural destiny.”

We go on to discuss the generational ideological divide between the youth and elders, where the youth are angered by Moon’s diplomatic gestures towards North Korea because they are too young to see the peninsula as one homogenous culture. Johnson elaborates, “In Korean society there is a respect for elder hierarchy. Age is a part of your societal status and level of respect. Many of the older generations are happy with President Moon reaching out to the North because their families were affected by the (Korean) War and the separation across the peninsula. The division across the country for them is still felt, whereas the younger generation isn’t affected as much. They are almost getting their information in a second-hand way. The younger generation is more likely to see the Northern regime’s crimes against humanity as unforgivable. However, because of the respect hierarchy, the older generation is heard more than the younger generation.”

She goes on to explain how the current diplomatic endeavours don’t necessarily represent public sentiment saying, “Social media certainly plays an effect on the news that gets spread, but as far as official opinions, the older generation certainly imposes their point-of-view deemphasizing the younger generation’s voice.”

In discussing the cultural divide between the two, Hamel (who plans on furthering her COD based education in a school in South Korea) explains how North Koreans have different linguistic dialects than the South. Generations of evolution after the war have further exacerbated the cultural divide. Explaining the youth’s discriminatory disposition against citizens of the North, she states, “The South’s youth hold classist superiority over the North’s citizens. There is a reluctance to take care of defectors in the South. It is comparable to the backlash against refugees in America. They don’t want to see these people suffer, however they also don’t want the responsibility of taking care of them and having to integrate them into their society.”

However, such animosities have been placated over as can be seen in this year’s Olympics with South Korean citizens cheering for North Korean athletes, particularly their figure skating pair.

“It’s a shock to people who aren’t familiar with Korean culture, but there is too much of a familial bonding to prevent respect between the athletes and the South Korean fans,” Johnson said. “Because of their strong sense of unity and family, even though there might be a political divide, the athletes of North Korea are still viewed by the South as just Korean. Their success during the Olympics therefore translates to South Korea’s success.” Hamel further elaborated, “South Korean skiers trained at a North Korean facility, and the North’s coaches were seen cheering for the South’s skiers during the games.” Johnson finishes the thought, “It’s more in reverence and memory than a reflection of current political or social unity.”

Ruminating upon what direction she would like American international relations to take, Hamel suggested lesser sanctions to remedy the sufferings of the North Korean citizens.

“Try to find a way to help their people without contributing power to the oppressive regime. We must try to bring some form of aid and relief to their people,” she said. She further describes a recent defector having tape worms and tuberculosis. “We must try to bring modern medicine in a greater capacity across the border.” However, a porous border would have to be, “heavily moderated to prevent weapons and black-money reaching the regime.”

Johnson said there must be attention paid to possible unintended consequences of improved relations between the two nations, “Because there is so much we don’t know about the North, we don’t know the repercussions of economically opening up the border more. Therefore, we need more lines of communication to better understand their culture and the daily lives of their citizens.”

Education can break down cultural stereotypes that prohibit the further development of sympathetic understanding and peace. Johnson elaborates on the benefits of COD’s Korean Club iterating, “Our goal is to educate you about the culture because there is so much more to Korean culture and history than what our American public perceives. We want to teach you more than just the romanticized parts of Korea; we want to discuss their realities.”

In discussing what makes COD a good place for students interested in taking their Korean studies to the next level, Hamel proclaims, “Both of our professors are from Korea, and they provide insight into Korean culture instead of just an American perspective. Having grown up there, they teach about the culture, the history and the richness of their traditions.” They encourage their students to go out to cultural events, and make learning about the culture extremely fun.

The Korean Club gathers weekly 4:00 on Wednesdays in BIC 2575, and will conduct a bake-sale on March 14th to celebrate the Korean Holiday White Day. On Valentine’s Day in Korea men give chocolates to the women, and on White Day the gendered roles in the couples are reversed. They will also celebrate Black Day on April 14th. Contrastingly, on Black Day gather with other single friends and eat jajangmyeon, made of black beans and noodles. If they are of single age they drink soju, a traditional Korean alcohol.

Johnson encouraged all students interested in Korean culture to engage with the language.

“For anyone trying to learn the language, it was designed to be phonetically and scientifically easy for you to learn. The grammatical consonants are natural sounds that make the syllables easy to pronounce. The alphabet is easy to decipher, and once you understand it everything else falls into place.”

I ask her how to say “peace” in Korean.

She replies, in both North and South Korea it’s, “Pyeong-hwa.”