Emerald Fennell’s sophomore film “Saltburn” was released into a slurry of social media anticipation across various platforms and continents. Considered a period piece of 2006-era England by Fennell, the movie speaks to a nostalgic Millennial crowd while enticing a younger, Gen Z audience through its campy filmography and controversial plotlines.

“Saltburn” made sure to feature all of the current pop culture phenomena: Eat-The-Rich, the obsessions of desire and surprising, but not shocking, displays of violence and gore.

Despite these ambitions and widespread anticipation, various writers and casual critics have been ultimately disappointed in “Saltburn.” I also agree. The film felt too overreaching and superficial, sacrificing plot for aesthetics despite an incredibly strong cast.

However, many were quick to defend “Saltburn” and Fennell, saying that it was a British film, and the American audience just wouldn’t get it. It becomes even more interesting to view Fennell’s social critique through a transcontinental lens. Through it, we can see how themes of class and horror compete between the American and British perspectives.

Within its literary tradition, America loves the rags-to-riches story. It epitomizes the American Dream. So, it comes as no surprise that our chosen mythology revolves around the superhero – born (or predestined) with otherworldly powers and abilities – but finding themselves in ordinary, often working-class conditions.

Superman literally descended from the heavens to end up in rural Kansas, while Spiderman is an orphaned child genius living with his financially-strapped aunt. Through their inherent talents, they are able to ascend to wealth, and the boundaries between the social classes are meant to be mobile. Subsequently, their status of growing power and wealth is revered.

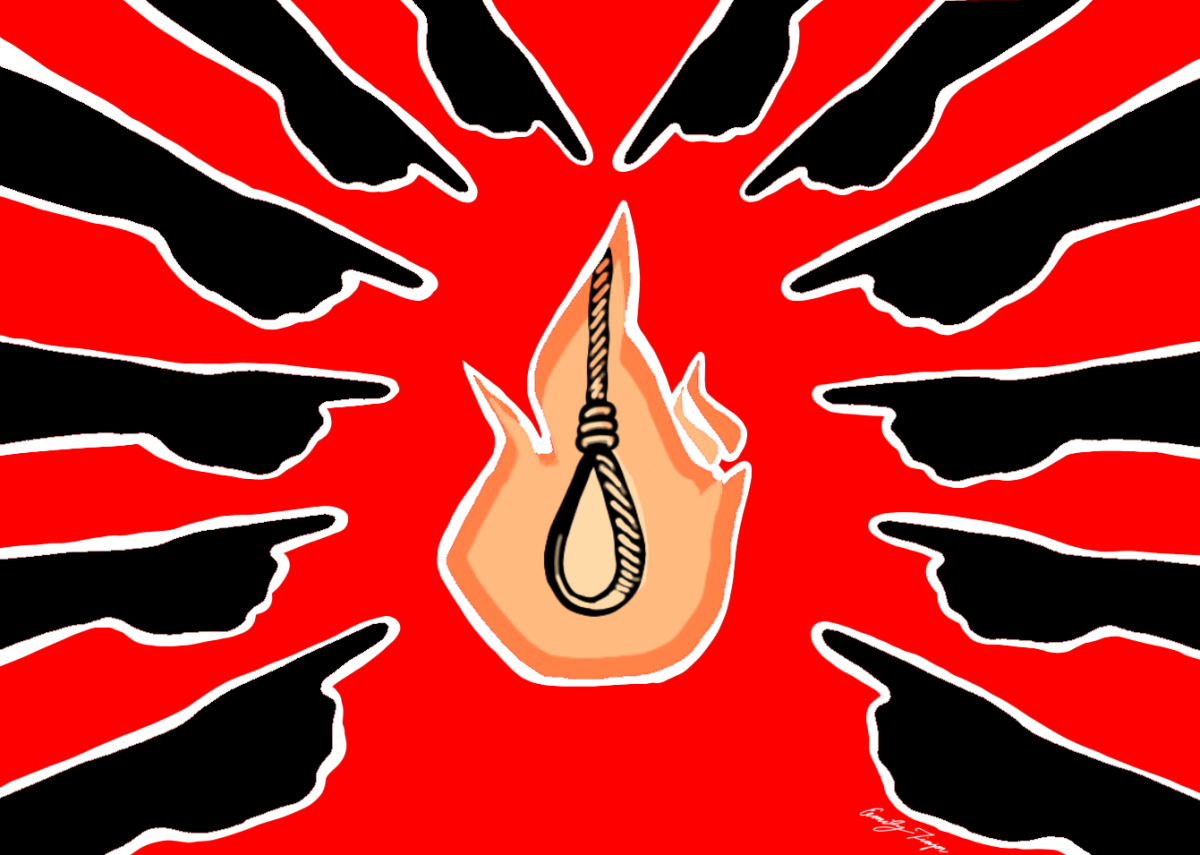

In real life, however, people are becoming more and more disillusioned with the American Dream. Many Americans think it is dead, which is unsurprising given the increase in wealth inequality. As such, people have begun to apply their critiques to those who have had major public success.

Currently, the most egregious thing that you can be is a nepotism baby or, as it’s widely called on the internet, a nepo baby. Nepotism is, for all intents and purposes, the practice of finding jobs through your connections, more often than not through your family. Thus a nepo baby is a celebrity or wealthy individual who started their success through their family’s connections.

This discussion sparked in 2022 with a Vulture opinion piece by Nate Jones, who identified the longstanding familial ties that current popular actors and singers had within their fields, allowing access to lucrative positions within a selective industry. The public has taken to identifying the lineages of pop culture icons, examining whether they have ‘earned’ their respective positions. Fennell herself has not been immune to these criticisms, as she grew up with a jeweler father who was heavily involved in celebrity circles.

However, the main character of Oliver Quick attempts and succeeds at his own social reckoning. His counterpart, Felix Catton, is the original blueprint for nepotism, quite literally born to inherit a title, a stellar education, and the Saltburn estate itself. Oliver is a threat to not only the Catton family but the British aristocratic system. Its roots are firmly planted in an ancient feudalist system. Unlike American social mobility, there is much more adherence and pride in one’s class.

Yet, Oliver still manages to maneuver around this class barrier, attempting to fit into the to-be aristocrat crowd with his friendship with Felix. He utilizes an unfortunate upbringing to garner sympathy from Felix. In this role, Felix is able to reckon with his immense privilege in this advisory role. Regardless, we see how cruel and insensitive the family can be to social outsiders through dear poor Pamela. Even helping the poor has its limits.

Yet, Oliver is able to subvert these long-standing traditions by using them against the family. The biggest threat then becomes the man who is a little too eager to ascend upward. To the British, this desperation is a cardinal sin. To Americans, it is a dream.

Unlike other forms of British media like “Keeping Up Appearances,” which mocks and makes caricatures of those who attempt to transcend class, Oliver is incredibly intelligent. The Cattons don’t recognize this, rather blinded by their own imagined superiority.

“Saltburn” is undoubtedly a Gothic horror. From discussions of Mary Shelley to the imagery of burial and the grave, there are many tropes of this classically British genre. It is not your typical American slasher where men in masks jump out at you. The real horror of Gothicism and “Saltburn” lies in the otherworldly, the things unseen and the words not said (another reason why the ending was so disappointing)

However, Fennell subverts the genre as she paints the traditional villain archetype as the protagonist. Oliver is marked with a perpetual outsider status and a disturbed personality as the calculating, secretly lethal danger, unveiled as the story is told.

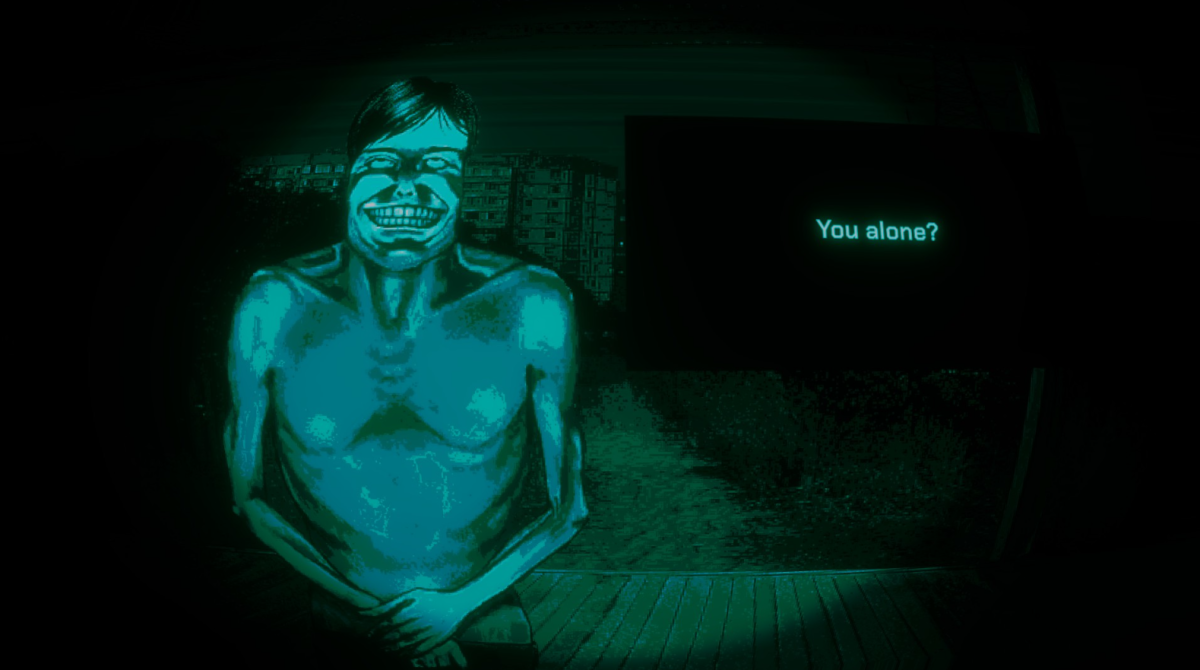

Oliver embodies an animalistic metamorphosis when he consumes the Catton Family, even their bodily secretions. Like a vampire, he maneuvers only when it is nighttime, quite literally spinning his spidery web as Venetia claims.

At the same time, Oliver has distinctly modern undertones. He is not possessed or demonic, but is painted as a sociopath. His separation from his adoring family and his class is of his own volition. His villainy becomes a much more individualistic affliction rather than supernatural.

I was able to discuss the film with Michelle Moore, professor of English at College of DuPage, who has spent much of her career analyzing the Gothic horror genre within literature and film.

Professor Moore says, “The castle is the site of horror [in England, whereas] the root of our gothic is in different places in the U.S.”

The castle is the only possible setting for a character like Oliver to truly ascend to the Gothic villain. It is a place where man is tested, either to give into his obsessive fears and desires or escape unscathed.

Moore adds, “The idea of ‘haunting’ is the living past. It is an idea of liminality.”

Oliver, by the end of the movie, loses any ties to his humanity, with his actual and ‘adoptive’ family in the Cattons. He is completely alone and tries to disregard the love he held for Felix, who was never going to reciprocate. Yet, materially, Oliver is extremely successful in obtaining access to the castle. Thus, Oliver lives within the living past of Felix but also the British class system. He will always be reminded of what he has lost, going from the haunting to the haunted.

While “Saltburn” was far from my favorite film of the year, it seems that Oliver is a much more radical character in the context of a British system. The discussions around class and setting are British mediums and to apply an American perspective seems reductive to Fennell’s work. It also applies an interesting comparison to the differences between American and British cultural differences.

For those interested in digging deeper into the genre, Moore talks about Gothic horror further in her class Film Genres MTPV2235.