Protesters ask ‘How many more women need to be murdered before we demand change?’

Demonstrators in Chicago wear blindfolds to protest society’s blindness to violence against women and to remember the women who have been silenced by femicide (photo by Gabriela Hernandez Chico)

December 11, 2019

The Mexican judge ruled it could not be attempted femicide because if Juan Carlos Garcia truly wanted to murder his sleeping wife during his savage baseball bat attack, he would have succeeded. After being released on bail, in the midst of a custody battle, a hired hitman shot Garcia’s wife dead in front of two of their children.

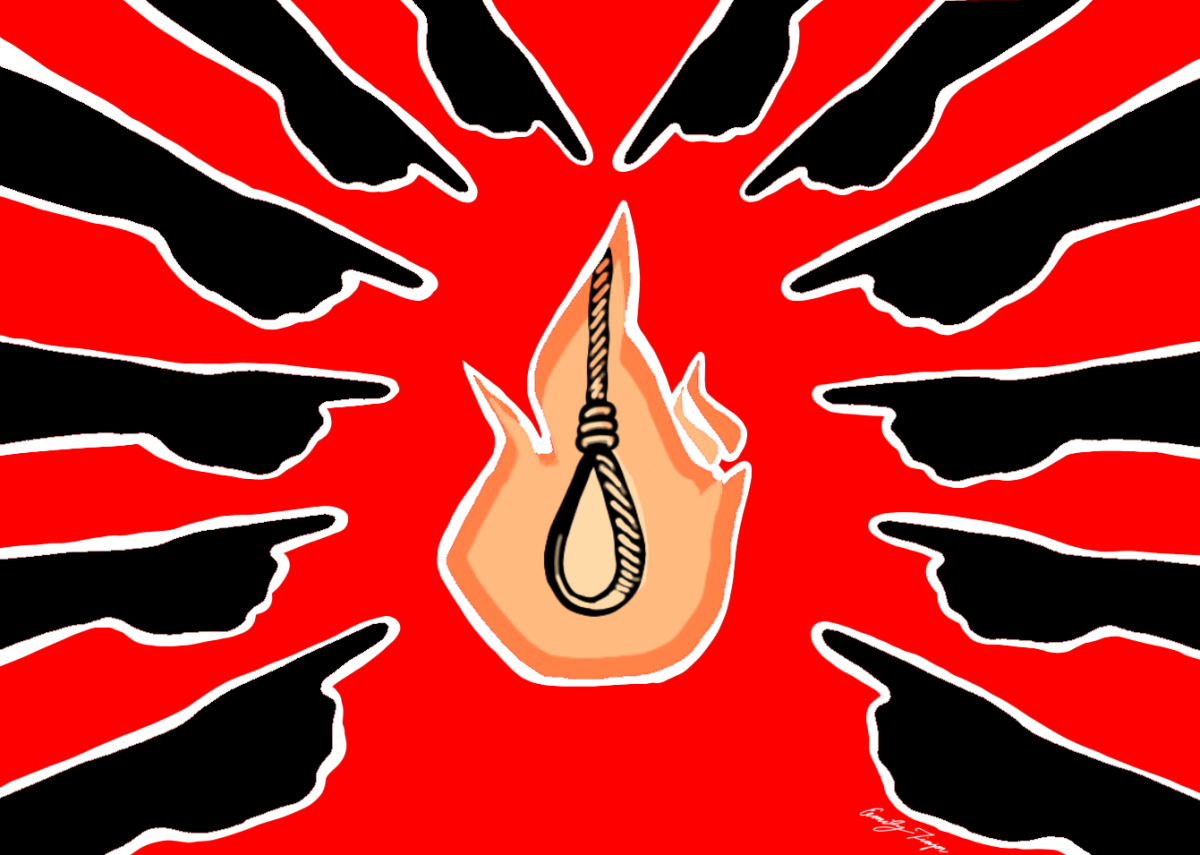

Carrying 100 purple crosses, each inscribed with a murdered woman’s name, protestors in Mexico City demanded authorities end judicial impunity for femicide and sexual assault. Across the world, demonstrations occurred Nov. 25 to mark the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women.

According to the United Nations, more than 87,000 women and girls were murdered around the world in 2017 in acts of gender-violence, or femicide. Fifty-eight percent were killed by someone close to them. On average, 136 women are killed by a partner or family member every day. Men are triggered by possessiveness and pride, with femicide viewed as the ultimate act of devaluing women.

In Chile and Argentina, women marched with handprints painted over their mouths to mourn the women who have been silenced. Twelve women are murdered every day in Latin America (U.N). Women laid under sheets splattered in fake blood in Panama City. Protesters in Nantes, France shouted “138,” the number of women murdered by current or former partners this year across France. Turkish protestors decried the murder of 300 Turkish women this year.

While critics have called the protestors extreme and denounced clashes with security forces, Gabriela Hernandez Chico said the women of her hometown, Mexico City, have no choice but to fight back.

“The current system is a death sentence for us,” said Chico. “I was assaulted four times; the last included a rape attempt. Women are dying daily. There are thousands of stories where women go to work or school and never return. These women can’t tell their stories, but I can.”

Now living in America, Chico is part of the non-profit Immigrant Solidarity DuPage’s leadership, which brings help to immigrants, including resources for women who have experienced gender violence. The struggle against gender violence is particularly meaningful to Chico because her sister was murdered last year in Mexico City in an act of femicide.

“We thought she suffered a little abuse at home, but we never knew the severity,” said Chico. “Her story is similar to so many other women. In Mexican culture, women are told to stay quiet when suffering domestic violence. Before my sister’s assassination, people didn’t want her to denounce the violence. All the signs were there. People could have helped her.”

Recounting many friends who have reported domestic abuse in Mexico City, Chico said with Latin America’s patriarchal society, even if women find the courage to come forward, they face misogyny in the judicial system.

“Women almost have to be dead to prove to officers they were abused,” said Chico. “Only then will they open an investigation. Authorities don’t recognize femicide. Extremely lenient judicial sentencing allows femicide to continue with impunity. We can’t keep calling violence private squabbles or part of daily life. We need to unlearn to tolerate the abuses our mothers and grandmothers suffered. Women everywhere need to empower one another to no longer be submissive to the abuses of men.”

“However, current laws are designed to protect the abuser, not the abused. Because of this, there are minimal social services or shelters to help women,” said Chico. “This creates a culture of oppression. If we are raped, we are told to keep quiet so the town doesn’t talk about us. Authorities, men and, sometimes, women say if you were raped, it’s because you were looking for it. You didn’t have to dress slutty or go out at night. We are denied the same freedoms as men. It’s a human right for women to walk in the streets free from violence.”

Chico said favorable legislation, social services and educational programs need to be created to help people identify what constitutes gender violence. Symptoms need to be recognized in the workplace, at school and among family and friends. The correlation between sexual violence and domestic violence must be understood. She said femicide typically begins with abuse in the household. The number of women receiving abuse from someone they know intimately is far higher than what is reported.

In America, one in three women, and one in four men will experience domestic violence in their lifetime. In DuPage County, that equals over 200,000 individuals. Kadri Ladewig, educational community coordinator for Family Shelter Service in Wheaton, the county’s only domestic abuse shelter, believes while it can be difficult to come forward, domestic violence unreported will only increase in frequency and severity.

“The U.S. is considered more progressive, but there are still some deep-rooted oppressive structures in the judicial and justice system,” said Ladewig. “Women’s rights are human rights; we need to work together to eliminate the system of oppression. We cannot let things remain how they always were. There needs to be a better requirement for domestic violence training for justice system individuals. In Illinois, both judges presiding over domestic violence court and family courts overseeing divorces and child custody are not required domestic abuse training. This often leads to dynamics of a relationship being misinterpreted. If an abuser seems calm and the woman seems erratic, training can help identify her trauma response. Often women who are not calm or clear about their facts are misinterpreted as lying.”

The shelter offers 43 beds (only 150 shelter beds are available across all Chicagoland), a 24-hour hotline for help, and advocates at the DuPage County Courthouse to guide victims through the complex judicial process of seeking an order of protection. The advocates also offer educational services to police departments on recognizing symptoms of abuse and how to utilize their services. All domestic violence calls are reported by police to shelter staff who offer the individuals support.

“In our society, individuals seeking help still receive a lot of judgment,” said Ladewig. “This helps perpetuate shame on the victim. Women are asked, ‘Why didn’t you leave?’ Many judicial systems believe you’re at fault for not protecting your children if you stayed in an abusive relationship. Clients often wonder, ‘If I leave, where do I go? I have no income’”

“People often fear others won’t understand their situation. Affluent people doubt people will believe them because their life looks normal from the outside. People from small communities or certain ethnic backgrounds fear the community talking about their private affairs. Members of the LGBTQ community can feel others won’t understand their relationship dynamics.”

Ladewig said the shelter’s hotline is completely anonymous and helps people recognize all types of abuse, including physical, emotional, sexual, financial and child abuse. Abuse comes from a partner trying to exert power. Domestic abuse is not about anger, and sexual assault is not about sex; they both involve an abuser trying to manipulate a power hierarchy.

(Joey Weslo: challenging toxic masculinity)

Through educational programs, trainers help partners establish healthy communication and recognize unhealthy behavior. Children are taught healthy masculinity instead of toxic masculinity. The power dynamic is broken down to help partners feel equal. Counselors also visit area schools to highlight teen dating violence, and fostering healthy relationships.

Tauya Forst, a criminal justice professor at the College of DuPage, said there’s a general cry for lengthier intimate partner abuse sentences and more protection throughout the process.

“Somebody can be charged, but it can be two years before they go to trial,” said Forst. “An order of protection can be used to keep the abused safe before the trial. Restraining order violations don’t result in mandatory arrests because that bypasses due process. It can be difficult to provide shelter for multiple children and a woman. This difficulty perpetuates the cycle of women not wanting to leave their abusers.”

Forst said while the Illinois-mandated 520 hours of training in police academies, like COD’s Suburban Law Enforcement Academy, seems like a lot, more domestic abuse education is required. However, she noted more departments are allowing specialized training for officers.

“People in criminal justice need to be trained to think creatively about individual cases, not just riding a particular theory or mindset,” said Forst. “Investigation should not come out in court, and cross-examination should involve attacking the facts without coming against the victim. This is where victimization can intimidate the abused. Advocates help the abused feel more comfortable in the courtroom where they can feel vulnerable. Advocates help with minute details like collecting personal documentation info if it’s in the perpetrator’s possession, or finding transportation when the perpetrator may own the car or the finances.”

Along with her husband, Forst taught a presentation to combat the normalization of intimate-partner problems. She said of 70 attendees, 85% had experienced some form of abuse in a relationship. She said only a quarter of that amount gets into the criminal system, and only 5% of those lead to a conviction.

“If you’re facing abuse, you must first confide in someone you trust,” said Forst. “I know someone in a domestic abuse situation, but the person will not report. Why won’t the person come forward? It often comes down to financial abuse, especially if the person has a low-paying job and multiple children.”

Ladewig said because the burden of proof is substantial, women often feel intimidated to come forward. Often in divorce proceedings, if a woman accuses her partner of violence, child abuse, or sexual abuse, and cannot meet the burden of proof, she is more likely to lose custody of her child because many judges rule her allegations as false. Women are also intimidated because the court system can be leveraged to keep the victim in court for years.

“From the beginning, women are scared of not being believed,” said Ladewig. “Officers are taught to look for visible marks. However, women’s bruises can take long to show, but her self-defense scratches on the abuser show right away. Often, an order of protection notification is sent to the abuser, and the abused must wait two weeks for further proceedings with minimal protection from the law. Abusers can react violently during this time. When a person tries to leave a relationship, they have the highest risk of being killed by the abuser.”

Chico believes for women everywhere there is a long road to change, but exerting pressure on authorities is the first step in ending the violence. She said women of lower socioeconomic means are being victimized by the law everywhere, but people and the media are starting to take notice.

“When someone ignores violence, you’re leaving an abuser without punishment,” said Chico. “This allows more crimes to continue with impunity. It takes courage to talk about your abuse publicly. When abuse happens one time, it’s likely to occur again. No woman should be quiet about this issue. We have to be strong and brave for each other. Together, we can change the world. Together, we can ensure my daughter will grow up in a world free from the violence so many of us have endured.”

(*for help call Family Shelter Service 24-hour hotline 1-630-469-5650)

.

(Joey Weslo: political take on #MeToo’s role in rape allegations)