Opinion: A “wildly intrusive” way to help older college students get their degrees

An experiment at John Jay College to get seniors over the final hurdle to graduation is worth watching

January 7, 2020

The John Jay College for Criminal Justice is known for training New York City’s future police officers and as Dara Byrne rose through the ranks of the college’s administration, she noticed a mystery right on her campus: why were 2,000 seniors, with only one year left to graduate, not enrolling in the fall?

“Students in that 90-credit zone, really close to graduation, were leaving,” said Byrne, when I talked to her by phone. “I couldn’t understand why because it’s counter to what you would think. You’re almost there. You’ve got only three, four, five, eight classes left.” Many of these students intended to return. “But data showed that very few of them came back to us,” Byrne said. “Thousands of students a year, never getting a degree.”

In 2018, Byrne and her colleagues decided to play detective using predictive analytics, which tracks student data to predict who is likely to graduate and who is not. In addition to being dean of undergraduate studies, Byrne has a second job as associate provost for undergraduate retention and it is her job to make sure John Jay’s students — mostly low-income and many the first in their families to attend college — graduate. Typically, colleges work on improving graduation rates by investing more in students when they first arrive on campus. But Byrne’s observation convinced her that she needed to turn this model around and nurture older, nontraditional students at the end of their college careers.

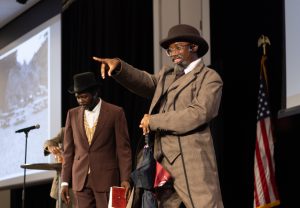

Byrne’s colleagues presented the results of their recent experiment in using predictive analytics at the Complete College America annual conference in Phoenix, Ariz., in December 2019.

Predictive analytics helped Byrne and her colleagues figure out which seniors were most likely to leave before getting their degrees. John Jay College sent more than 10 years of student data to a nonprofit organization, DataKind, and its data scientists figured out which attributes were associated with dropping out at the very end of a college career. Twenty-four data points, such as financial aid status, plus a dozen calculations, such as falling grades, rose to the top as important indicators.

In the spring of 2018, DataKind returned a list of more than 1,100 rising seniors who were at risk of dropping out of school. Byrne hired three employees plus a student liaison to give these students extra academic advising and financial aid. Because 1,100 students created too large a caseload, the school especially focused on 380 students with the highest risk scores.

Byrne calls this level of advising “wildly intrusive,” with advisers telephoning and forcing these high-risk students to come in for face-to-face meetings to learn about their problems. Many of the students had already spent more than four years in college and had exhausted their federal and state financial aid. Many had taken on more part-time work to pay for school.

“It’s exactly those financial pressures that make students think about not coming back,” Byrne said. “Emergency funds are critical…It’s amazing to see that $300 is what is standing between someone and a college degree.”

John Jay gave many of these students aid that they otherwise wouldn’t have qualified for to pay small, unpaid tuition bills. Even mediocre students received these “emergency funds.”

“There’s not a lot of infrastructure for students whose performance is declining over time,” Byrne said, noting that more than half of the school’s graduates go into public service, from police and firefighting to social work and youth nonprofits. “We think a 2.5 student [C+ student] is just as valuable as 3.0 [B student].”

The “wildly intrusive” advisers were encouraged to remove administrative roadblocks, sometimes bending college rules on removing and repeating courses. Byrne told me about one student who needed to retroactively withdraw from a class where she did not do well. The school allows students to withdraw from classes if they are experiencing mental health challenges but this student didn’t have any mental health documentation of the domestic violence she suffered that semester. Her adviser advocated for her and helped to gather other forms of documentation. That student’s exemption from the rules eventually led to a policy change that allows for the program’s advisers to advocate for students instead of requiring students to pay for a mental health professional to document a mental health crisis.*

After one year of Byrne’s interventions, which John Jay calls the Completion for Upper Division Students Program, 51 percent of the 380 students identified as high risk and targeted for help graduated in the 2018-19 academic year. In the previous year, before the college had started this experiment, only 47 percent of the students that the DataKind algorithm would have identified as high-risk seniors completed a college degree on their own within a year. That’s a four-percentage-point jump in the graduation rate for this group.

The gains were primarily achieved by an even smaller subgroup of 180 students who had the very highest risks of dropping out, according to the algorithmic predictions. More than half of them were Hispanic, much higher than the 46 percent Hispanic population of the overall student body. And they were notably older: 38 percent of this very high-risk group was at least 25 years of age. This very high-risk group saw a six-percentage-point improvement in their graduation rate, from 33 percent previously to 39 percent after the data-driven intervention. (The remaining 200 students in the intervention actually saw their graduation rate deteriorate slightly from 64 percent to 62 percent.)

Among the larger group of 1,100 students who had originally been flagged for risk, nearly 73 percent graduated within a year. Without the program, the school had expected only 66 percent to graduate within two years.

Those jumps helped increase the overall graduation rate at John Jay College, which has 13,000 undergraduates, by 2 percentage points, according to the college’s estimates. It calculates that nearly 38 percent of its students who started in 2015 received a bachelor’s degree within four years and almost 52 percent of the students who started in 2013 received a bachelor’s degree within six years.

Graduation rates at John Jay were already trending upward because of other things the college has been doing. But without this predictive analytics experiment, John Jay estimates that its four-year and six-year graduation rates would have grown to less than 36 percent and 50 percent, respectively. It’s one of the first times I’ve seen a college try to measure the effectiveness of predictive analytics and compare it to what might have happened otherwise.

Of course, predictive analytics, counseling and financial aid come with price tags. Two foundations, MasterCard and Robin Hood, footed John Jay’s bill for DataKind. (Companies typically charge colleges $300,000 a year for providing predictive analytics services.) And the Price Family Foundation* gave John Jay $800,000 to hire extra staff and give students emergency grants.

Because John Jay is part of the City University of New York system, Byrne is well aware of the financial pressures at public institutions. She argues that it can be affordable if colleges hunt for cheaper open-source data analysis and reallocate existing advisers. Getting more seniors to graduate seems worth the effort. But ultimately, sleuthing out and solving each student’s obstacles one at a time is slow, painstaking work.

*Clarification: This sentence was modified after publication to make clear that program advisers are involved in the new policy.

*Correction: This story previously misidentified the Price foundation that donated funds to John Jay College. The Price Family Foundation that donated funds has no connection with Sol Price, the founder of Price Club.

This story about John Jay College graduation was written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.