Often overlooked in the sphere of U.S. politics and public service, Native American diplomats and representatives have played a central role in serving the public in the nation and abroad. To highlight this, the Department of State hosted a virtual panel with over 145 participants from the United States and abroad on Nov. 29. The event was hosted in honor of Native American Heritage Month in November. Three U.S. diplomats of Native American heritage shared their journeys and how the work they do is informed by their background.

One of those speakers was Jennifer Barnes Kerns, a U.S. ambassador from the Chickasaw Nation. She described how one of her motivations for becoming a U.S. diplomat was to change people’s limited perceptions of Native Americans.

“When the average U.S. citizen thinks about Native Americans, they think about warriors that are dancing or storytelling. Diplomats don’t necessarily immediately come to mind when they think about Native American tribes. That’s a big mistake. Diplomacy has been going on since the arrival of colonists, way back,” Kerns explained. “Indigenous people are so gifted in so many areas, it’s time our nation’s diplomatic quarter reflects that we can be warriors and diplomats, and the Department of State gives us the opportunity to be both.”

Kerns also described how being Native American can give her a unique perspective in the work done for U.S. foreign policy. At times, being Indigenous can help establish rapport with international groups who share similar struggles.

“The United States is sometimes viewed as a big brother overseer who’s coming in to tell everyone how to do this, how to live their lives. That’s not always warmly received,” she described. “I think people have that misconception coming in, so being able to share those stories really helps them to connect and help them to know that my people had been oppressed by the U.S. government, that we had come to peaceful terms, that now we work together, and they do respect the sovereign rights of my Chickasaw Nation.”

Sharri Clark is a senior advisor in the Department of State’s cybersecurity task force, which works with the combination of her Harvard doctorate in Anthropology and her degree in computer science. She is also a cultural heritage expert, as a person from the Cherokee Nation.

“Many of our members have deep roots in Indian Country, which is a really helpful resource for the department and its diplomatic work,” Clark said.

Sharing aspects of Native culture enriches the diplomats’ work, though Clark mentioned the challenge of misconceptions people have about Native Americans, based on movies and other caricature portrayals. With 574 federally recognized Indigenous nations in the U.S. alone, each one is very diverse.

“There’s huge variation in the kind of lifeways we have, the traditions we have, the language,” Clark said. “That is an incredible richness that we can share with other nations and contribute to the department in the work of diplomacy. A lot of that would be very helpful to communicate with the rest of the world, and I think they’re interested and want to hear about that.”

She mentioned the benefit of the Department of State being a platform for stories about Indigenous people, vital to raise awareness about issues Native American communities across the country are facing. One important matter Clark described was sovereignty for Native nations to govern themselves on their rightful land.

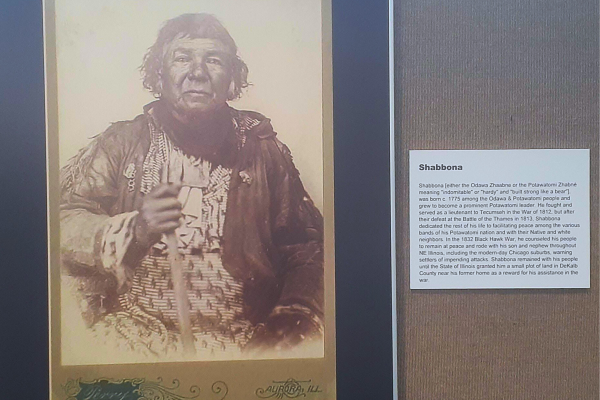

John Paris, a COD History professor and lead of the Native American Studies Committee, gave an overview of a local landback initiative by Prairie Band of Potawatomi. They have worked for years with state and federal agencies to repurchase a two-square-mile plot of land near Shabbona, Ill. It will be designated as the first Native-owned land in Illinois since their forced removal in the 1830s.

“Chief Shabbona was a beloved leader who both served his people and helped protect new settlers during the Black Hawk War in 1832. He was granted a piece of land in southern DeKalb County but that was illegally seized and sold while he was away visiting Iowa, where most of his people were forcibly relocated to,” Paris explained. “He was awarded a new piece of land near Ottawa, where he lived out the rest of his life, but the seized land is both an unaddressed injustice against him and symbolic of the illegal, immoral and unjustifiable seizure of Native lands in Illinois.”

The preservation of land and cultural heritage is intertwined, which is why federal workers like Clark work to protect Native American heritage objects being stolen from the original tribes.

“In particular, there’s an auction house in France who is receiving, not always clear how, and selling Native American sacred and cultural heritage,” Clark mentioned. “We’ve been trying to work with the entire agency for justice, the Department of State is trying to ensure that that stops.”

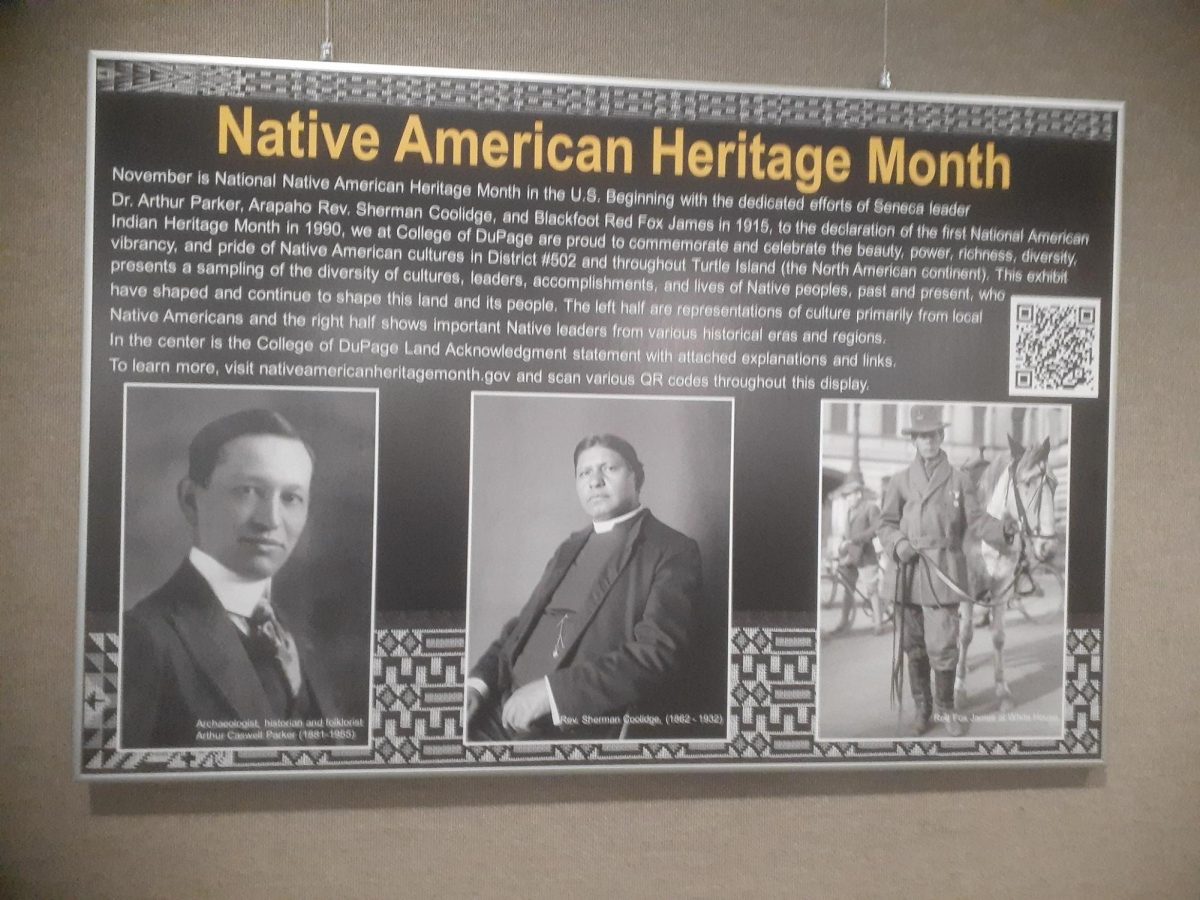

Clark hopes these issues can be resolved by having more Native American diplomats. While many Native American people were forced to assimilate or hide their identity in the past, Clark mentioned that there is a strong, though unknown, presence of past U.S. ambassadors who had Indigenous ancestry. Some of them are displayed on the Native American Heritage Month display in COD’s International Hall.

“We’re very happy to discover people who have ancestry are using this in diplomatic work,” Clark said. “It’s not necessarily something someone wears on their sleeve, but it’s very helpful and always interesting to people around the world to try to understand how people who grew up belonging to a tribe or a nation, which can be familiar with people around the world, works here in the U.S.”

Clark described how growing up in the Cherokee Nation, as well as with the Choctaw people, gave her insight into alternate government forms that helped her relate to people in other countries.

“It really opens a line of communication and understanding connection with people, that I actually had grown up in a tribe and understood a tribal government and tribal rules,” Clark said. “Being a part of a community where there’s a specific culture of how you communicate, how you interact. That was really helpful in these situations, not everybody can relate to that.”

She described how she worked in an embassy that had Native American art displays, and Choctaw ambassador Ross Wilson used the artwork as a bridge to connect with the people during contentious discussions.

“This was a way to reconnect, get past the difficult points of conversation, that made people relaxed,” Clark described. “They were interested by the art. He would talk about that and still get to the diplomatic issues at the same time. I think it’s really helpful to get that different perspective that we had, having grown up in these cultures and environments.”

Another story of how U.S. foreign services and Native American nations have worked together came from U.S. diplomat Christine Pedersen of the Cherokee Nation. Pedersen described her work in the American Citizens Services, where she helped American citizens in foreign nations escape violence. She once facilitated the repatriation of a Navajo man who had passed away in Mexico.

“His family couldn’t afford to repatriate his remains. One of my colleagues reached out to ask if any nonprofits could help because they wanted to get him back,” Pedersen described. “What was interesting was a lot of my colleagues didn’t understand that the Navajo nation was its own sovereign, with its own resources, so it didn’t mean having to find a nonprofit. I actually reached out to the Navajo Nation, and they had their own funding specifically for this purpose. In this case, we were able to repatriate this person’s remains back to the Navajo Nation, by connecting Navajo Nation resources to the American Citizen Services team in Tijuana, which was really rewarding.”

Pedersen began in the Marine Corps as an Arabic translator, before becoming a diplomat in the Kosovo embassy, and later working in Washington D.C. for the spokesperson on Libya.

“As it pertains to my Native identity, sometimes growing up as a Native American girl and woman, it felt like you were straddling two different worlds,” Pedersen described. “Sometimes the elephant in the room can be when we talk about the history of our families, our nations with the U.S. government, it is a dark history at some points. We have to acknowledge the past, as we highlight the progress.”

Pedersen provided her perspective on how to reconcile these opposing aspects as she serves in the U.S. Department of State.

“Where I would challenge people, some people think it’s a contradiction to not only work as a public servant but represent these policies, our U.S. foreign policies overseas,” Pedersen says. “I would say that for me personally being a Cherokee woman and a committed public servant for this government lends credence to the extent of my commitment to ensure that we as a nation live up to American ideals that reinforce our foreign policy. Our heritage bolsters the importance of those values. That’s why I think it’s a great place for people to work if you’re Native American or other minority groups that feel that same contradiction.”

Kerns also offered supportive advice to students applying to the Department of State, especially those from minority backgrounds who may feel intimidated.

“Don’t fool yourself out, you’re smart enough, you’re good enough, your nation needs you,” Kerns said. “Native people tend to be very humble, I too have seen that as a disadvantage in the department. You have to be more assertive, you have to be more confident. Do not rule yourself out. The worst that can happen is you have to take the test again or reapply for another job on the civil services website.”

To get involved with Native American-focused initiatives on campus at COD, Paris recommends students start with campus activism and extend their work to connect with local Native American groups.

“Students can organize and form social and activism clubs, work with various levels of their colleges, including student council and college governance, and reach out to faculty and administrators on the curriculum development side to promote Native issues, curricular topics, and amplify their own voices,” Paris advised. “Also reaching outside their institutions of learning and partnering with Native organizations in the broader community on collaborative projects, events, fundraising and advocacy is another good strategy.”

For students interested in applying to an internship, visit the Department of State careers website. To learn more about Native American studies at COD, take a literature or history class or contact John Paris.