History in Your Backyard

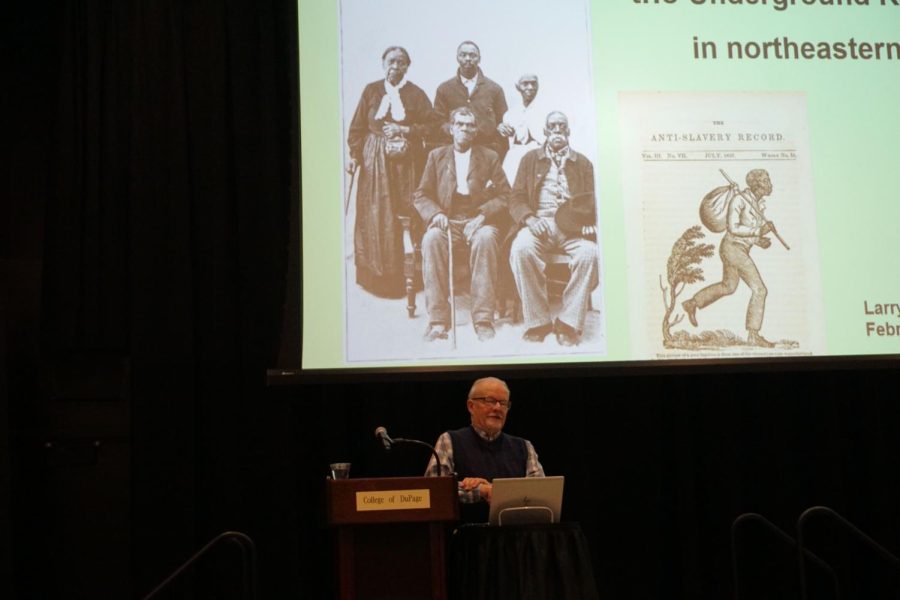

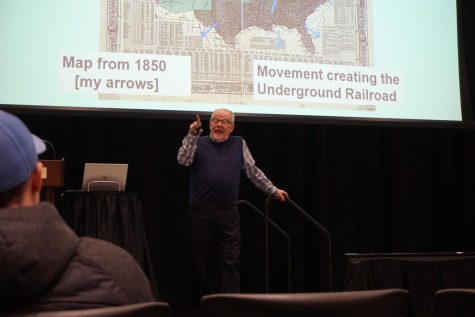

As part of COD’s events for Black History Month, guest speaker Larry McClellan discussed freedom seekers and the Underground Railroad in Northeastern Illinois.

February 13, 2023

History is closer to us than anyone might think. This past Wednesday, as part of a series of ongoing events for Black History Month, Larry McClellan came to COD to discuss how the Underground Railroad crossed through Northeastern Illinois, including DuPage County. McClellan is an emeritus professor of sociology and community studies at Governors State University. He has an upcoming book titled “Barefoot to Chicago: Freedom Seekers and the Underground Railroad in Northeastern Illinois” based on his decades-long research and focus on the Underground Railroad in Illinois.

Before the talk, McClellan was surprised to find amongst the audience an old colleague, Glennette Turner, a resident of DuPage County and collaborator of research on the Underground Railroad in NE Illinois. McClellan went on to explain how uncovering the hidden history of the freedom seekers, the term used to define people escaping from slavery, is the result of a collective effort of researchers passionate about the topic.

While the name indicates otherwise, the professor explained how this system was neither underground nor a railroad.

“It was the aboveground network responding to assist freedom seekers who were on their journeys,” McClellan explained. “In the 1830s, the great technological excitement was the railroad. It just so happened that that language fit perfectly. [People thought,] ‘Wow if we call this the Underground Railroad, then we’ve got passengers, conductors, etc.’”

According to him, another plausible explanation could be that slave-catchers commented amongst themselves that the missing fugitives had ‘disappeared on some underground road.’ The phrase caught on, and the image of the railroad then developed and circulated.

He highlighted the key location of Illinois as a connecting point between major waterways that allowed freedom-seekers to reach liberty. Chicago – and nearby DuPage County – marked a divide, a bridge between free and slave states. Hence, why many freedom seekers were bound to cross this state on their way to safety.

“[We are now] reframing the story of heroic white people to that of brave black freedom seekers,” McClellan explained. “It’s the story about the people making the journeys, escaping from the south.”

The professor explained how both Black and white families joined forces. Among white activists were Charles V. Dyer, also called a stationmaster of the Underground Railroad, and Allan Pinkerton, a detective who probably started his undercover spy work assisting runaways in Illinois. They, amongst other white families, responded to help freedom-seekers.

Besides, McClellan explained how a group of Chicago Black families realized they had to be of assistance to freedom-seekers who were coming through the city. They decided to break the law and organized themselves. Most of the Black activists were under the leadership of couple John and Mary Jones, whose work is reflected in the success stories of freedom seekers.

“What we’ve discovered is that in the late 1840-50s, the young Black activists connected with young white activists, and we have in Chicago in the 1850s, the first civil rights movement in Illinois where Black and white people are working together to assist freedom seekers,” McClellan said.

“Papers like the Western Citizen, which had an abolitionist stance, were not just newspapers but organs of political groups,” he said, highlighting the relevance of newspapers at the time.

More so, McClellan stressed how the majority of the paper’s subscribers were part of the Railroad web, which strengthened their connections. This was one of the many factors that came into play within the system of allies of the Railroad.

Overall, the discussion emphasized how at one point both Black and white people had united for the common goal of ensuring freedom seekers reach free land. Ultimately, this complex web of collaborators achieved their plan by helping a large number of people, not without their hardships.

Now, there is an effort to honor this rich history. McClellan, along with other colleagues and the help of the National Park Service, commemorated the Ton Farm, located at Chicago’s Finest Marina, as a major point of the Railroad in Illinois. He plans for there to be many more of these recognized historical markers in Northeastern Illinois. He ended his detailed talk with a round of questions from the audience, reminding everyone to do their research, especially during Black History Month.

Professor David Swope, who manages the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion spaces here at COD, concluded the event by saying, “Thank you all for participating in this aspect of American history. We (educators) are appreciative to work together to bring to you stories that are seldom taught in the classroom. The majority of that leaves out stories about American history, and that is why we do Black History Month, so that we begin to tell the depths of American history, so that we can be better together and more informed.”

For more events on campus during Black History Month check COD’s website.