Getting rid of the ‘gotcha’: College students try to tame political dialogue

Rebelling against political discourse that polarizes people, new campus groups seek common ground and informed discussion of hot-button topics

Laura Pappano, for The Hechinger Report

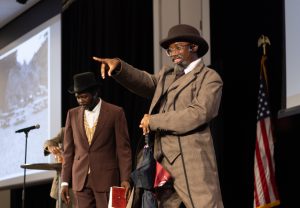

Julia Pascale, a sophomore from Baltimore, and Kyle Herbstreit, a junior from Stevensville, Michigan, discuss the death penalty during a session sponsored by WeListen, a bipartisan student group at the University of Michigan.

April 1, 2019

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — Tempers are flaring again over “free speech.” But while adults shout and Tweet across the political divide, college students are organizing civil campus discussions — with both sides at the table.

In the wake of violent political protests on campuses around the country, some students have stepped away from the fray and sought what’s been lacking: space for reasoned conversation, listening and middle ground. The hunger for moderation comes with rules that emphasize facts, ban personal attacks and respect ideological opponents.

It begs two questions: Are we allowed to feel hopeful? And, can we learn something?

These students are hardly “snowflakes.” They’re plunging into touchy subjects like prison reform, immigration, the government shutdown, teachers unions, health care for all, abortion, gun control and even — depending where they are — agricultural subsidies.

“The expectation is that you come in and you are willing to hear anything people might say,” said Christina Laridaen, a senior from Prior Lake, Minnesota, who is the outreach coordinator for the Minnesota Bipartisan Issues Group at the University of Minnesota.

What started with six friends talking politics a few years ago now draws 40 every Thursday at 7 p.m. to Coffman Memorial Union for organized discussion on preselected topics. The group has a logo (donkey and elephant butts form a heart) and motto (“politics without the yelling”).

Although the sessions attract “highly political people,” Laridaen said, they also demand “a recognition of other people’s humanity: ‘I have these values and they are important to me. And somebody has these other values and they are just as important to them.’

The notion that people who disagree with you are not evil or ill-intentioned is at odds with the prevailing national climate. To be fair, campuses remain split and charged, but there is also a new drive for meeting spaces and a quest for common ground.

“As a conservative, it’s an open space to talk about and share my views; … most of the time, you get shunned. That doesn’t happen here.”

Kyle Herbstreit, junior, referring to the University of Michigan’s WeListen club

Students are forming new clubs, reviving old ones, launching bipartisan journals and organizing events. It’s happening across the country at campuses large and small, public and private — from Washington State University to Tufts — and getting a boost from organizations like BridgeUSA, which started in 2016 at Notre Dame and the University of Colorado Boulder (and whose chapter at the University of California, Berkeley, began after violent protests around a planned visit by Milo Yiannopoulos in 2017). In the past year, BridgeUSA has grown from four to 24 campuses and will hold its second summit April 26 in Dallas.

“It’s about putting a face to the other side,” said Daniel Lewis, a junior who led a day-long Policy Challenge on March 30 for Tufts CIVIC, which stands for Cooperation and Innovation in Citizenship and is described as a “multipartisan discussion forum.” Said Lewis, “It’s much harder to scream at someone in front of you than someone across the room or across the web.”

Julie Wollman, president of Widener University, who launched the Common Ground Initiative there in fall 2017 to lead regular conversations on campus for students and faculty, thinks people simply “want to find a better way.” For student groups that means creating club leaderships that are politically even, plus putting emphasis on rules and sharing nonpartisan facts at each session.

WeListen, a club started by University of Michigan students in 2017, is aggressively balanced. Its current co-presidents, Kate Westa, a junior from Grand Rapids, Michigan, and Brett Zaslavsky, a sophomore from Glencoe, Illinois, are matched political opposites (she right, he left). The executive board “is a 50-50 split, half conservative and half liberal,” as is the six-member “content team” that provides background research for each gathering, said Evon Yao, vice president of outreach.

Even the composition of discussion groups at events is balanced.

As 49 students entered Room 110 in Weiser Hall on a recent Monday evening, they dropped backpacks and grabbed slices of cheese pizza. But not before “checking in” on a laptop, where they rated their political orientation overall and then on the issue of the evening —the death penalty — by indicating how strongly they felt and where they fell on a spectrum from “immoral and should be illegal” to “ought to be used, especially for heinous crimes.”

A student-built algorithm then created a composite score for each attendee and sorted individuals into eight groups that optimized political and ideological diversity within each. Groups also had a secret “moderator,” trained in conflict resolution, to keep talk fair. (Moderators had gathered before the session to preview ways to resolve possible tensions, such as talk becoming a moral face-off, in which case Zaslavsky advised, “bring it back to policy.”)

Before reporting to assigned tables, students received a two-page fact sheet (including, for example, “There have been 1,492 executions since 1976”; “from 2000 to 2015, 43% of inmates killed under the death penalty had received a mental illness diagnosis”). They took in a slide presentation on the history of the death penalty (the Code of Hammurabi, views of the Founding Fathers).

Then came verbal guidelines. “People have good intentions and genuinely believe what they say,” Westa announced. Zaslavsky ticked off reminders — “be conscious of body language,” “no personal attacks,” “no Googling facts.”

He added that people can change their views. “Don’t freeze people in time. You see a lot of the same people week after week. . . . Keep an open mind.”

To set the stage for civility, conversations began with five minutes of nonpolitical chit-chat. Then, students in Group 7 — which included a mix of college years, majors (history, mechanical engineering and chemistry) and geographic origins (Michigan, Maryland and New Mexico) — delved into a death penalty discussion that ranged wildly.

There was mention of Truman Capote’s “In Cold Blood,” Ted Bundy, Osama bin Laden and Hitler. They debated the death penalty’s purpose (deterrence or retribution?), considered the soaring cost of chemicals for lethal injection, the mental health of death row convicts, the risk of wrongful execution, the cost of life imprisonment versus the death penalty — even whether the death should be painful for those guilty of heinous crimes. To which Tyler Ziel, a soft-voiced junior with black-framed glasses, suggested that lessening suffering at death may not be about the convict: “Is the humanity for them or for us? So we are not so barbaric?”

political dialogue

In the end, nothing got decided. But that’s the point. There are no “winners.” Bipartisan discussions are about letting go of “gotcha’s” and hearing others’ thoughts.

This tone attracts regulars like Kyle Herbstreit, a junior from Stevensville, Michigan. “As a conservative, it’s an open space to talk about and share my views,” he said. Because the campus is so liberal, “most of the time, you get shunned. That doesn’t happen here.”

It’s not entirely clear how or why the desire to share stances — rather than set fires or chant over opponents — is gaining traction nationally. Perhaps it is the byproduct of a generation that, unlike its older siblings, seeks to solve problems, not just join sides.

That distinction struck Jacob Heinen, a former vice president of the Washington State University College Republicans club. Although he once proudly spray-painted “Trump” on a wall that club members had built on campus, Heinen grew tired of what he saw as a focus on antagonizing others to get attention and “just making people mad.”

And when the president of his university’s College Republicans, James Allsup, surfaced at the “Unite the Right” rally in 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia, Heinen resigned from the group – and helped to start a nonpartisan Political Science Club on campus. “I felt there were more efficient ways to communicate conservative values,” said Heinen, now a senior. “I want to engage people in honest conversation.”

“It’s much harder to scream at someone in front of you than someone across the room or across the web.”

Ditto, you might say, for Andrew Solender, a junior at Vassar. He’s hardly conservative — a Democrat who worked on Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign — but he found the far-left antics around a visiting Cornell law professor’s talk on free speech polarizing, allowing no room for those deemed “not progressive enough.” It led him and friends last spring to start the nonpartisan Vassar Political Review. (A recent headline: “Opinion: New York Democrats should Vote for Republican Mark Molinaro for Governor.”)

Creating a fair and cordial space, student leaders say, starts with interrupting knee-jerk political alignments to focus on issues. In Michigan, WeListen’s approach is so in demand that club members get called to lead discussions for other groups (recently on immigration at the university’s Osher Lifelong Learning Institute and at Ann Arbor’s Greenhills School).

“We go into the conversations assuming we all want the same things, like safety and freedom. It has changed how I talk to people on the left. I have made a lot of friends.”

Sarah Wagner, graduate program coordinator in the psychology department at the university, had attended WeListen sessions as the only staffer among undergraduates before she organized, last April, a version for faculty and staff. About 50 people now meet at lunchtime every other month.

“Sometimes you find that you have the same idea as someone else who is a far-right Republican,” said Wagner, who leans left and has become friends with people she would not have otherwise gotten to know. She wondered aloud: “Would we have had this conversation if we started with our political affiliation?”

It’s a fair question. Being forced to explain her views, said Wagner, has made her think deeply about what she believes and why. She’s also heard perspectives she would not otherwise encounter. During a conversation on mass incarceration, she said, “at my table we had six people and four had immediate family members who had been in and out of prison throughout their lives.”

Wagner prizes the sessions because people “get to practice the skill of having difficult conversations.”

That’s something typically avoided, but which students must learn to do, said Wollman, the Widener president. “We have young people at a place in their lives where they are asking, ‘How will I deal with this when I am in the workplace?’ ”

This is a challenging moment because just as colleges seek greater diversity of thought and experience and “throw together all these people who are very different” to broaden students’ exposure, Wollman said, “our country feels like it is working against that. Instead of bringing people together, it is dividing them and highlighting differences.”

WeListen co-presidents Westa and Zaslavsky said participating has changed their perceptions of their political opposites. Before, Westa said, she saw liberals as opponents who forced “a lot of abrasive conversations” whenever she set up a table on campus to promote Young Americans for Freedom, a conservative group that she helps lead. Zaslavsky admitted to thinking “people on the right were beholden to special interests or they were thinking backwards.”

Pressed to see how others come to beliefs, rather than just aiming to change minds, reveals commonalities, both said. “People’s hearts are in the right place,” said Zaslavsky.

“We go into the conversations assuming we all want the same things, like safety and freedom,” said Westa. “It has changed how I talk to people on the left. I have made a lot of friends.”

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.