Free Hugs on the Front Lines

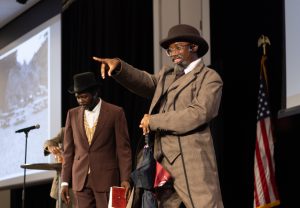

For COD’s Black History Month, activist Ken Nwadike Jr. spoke about how he uses love to overcome trauma and de-escalate protests.

February 20, 2023

California-based activist Ken Nwadike Jr., “The Free Hugs Guy,” uses activism to overcome trauma and bridge divides between the Black community and police officers at the front lines of protests. He told COD students his story of growing up in homeless shelters before becoming a track star and using that passion to help others. As he shared his message of cooperation, members of COD’s Student Leadership Council asked for advice on how to bring together student cliques on campus.

“Three things that I feel bring us all together are sports, music and food,” Nwadike replied. “If you can use any of those three things, then other stuff that we allow to divide us, it all stops.”

He related this to his work organizing workshops between citizens and police officers. At a Detroit youth shelter, children and police played an energetic game of dodgeball and ate lunch together, before a discussion about community policing.

“They sat on the floor at the same level talking about what change can look like,” Nwadike described. “The police were in plainclothes, to reduce their [the kids’] fear, seeing the police wearing the same Jordans or basketball shorts.”

Being an athlete also helped Nwadike develop leadership. At age 15, when his family lived in a homeless shelter, a coach encouraged Nwadike to join the track team. He soon became the third-fastest track star in California. Into adulthood, he organized the Half Marathon on Hollywood Blvd., which gained national attention and raised $1 million for the Covenant House homeless shelter in Los Angeles.

“The kids at the shelter, the few I’ve kept up with, have started families, went back to school and are doing well,” Nwadike said. “There were a few that slipped through the cracks, and we don’t know where they are.”

Audience members urged Nwadike to open his own youth shelter. He has served as a peer mentor for decades, showing them that he rose beyond the harsh conditions of his childhood into an activist and humanitarian.

“It’s important for me to teach them follow-through. A lot of the things the kids said they were going to do, like go back to playing basketball or enroll back in school, every time I would check back in, they hadn’t even started yet,” Nwadike said.

One way he did that was going to the Boston Marathon to support runners in the wake of the bombing. After a year of intense training, he was unable to qualify by just a few seconds. He didn’t give up and decided to show support in another way, with his Free Hugs shirt. Though he was nervous that nobody would respond, Nwadike inspired a six-hour stream of hugs from runners. This video went viral, titled ‘The World Needs Love’ on YouTube, and Nwadike was invited to speak to media outlets all over the nation.

Not only did Nwadike teach those kids the importance of persevering on goals, but he also made them feel seen. They urged him to continue the Free Hugs Project, especially as a tool to de-escalate tensions during protests.

“I knew how important it was. I used to be a homeless kid who sometimes tried my best to be invisible,” Nwadike explained. “Now these kids felt like we shouldn’t be invisible, because people should see us for our kindness. Just because we’re going through hardships doesn’t mean we’re bad people.”

He reminded the COD audience it takes perseverance to bring different groups together, whether in campus social work or political activism.

“I don’t want any of the young people in this room to think that starting a movement, creating change, won’t come with challenges,” Nwadike warned.

Nwadike discussed how the constant exposure to violent police encounters and unjustified shooting causes collective trauma to Black people in America. At the age of nine, Nwadike witnessed police raid his childhood home and arrest his father. It left his family homeless and fearful of the police, in the already-polarized atmosphere of Los Angeles in the 1980s and 90s.

The audience asked Nwadike how he responds to this trauma. He found healing through his faith and Martin Luther King’s legacy of peace. He also mentioned how important therapy is, especially for minority or immigrant groups.

“Growing up, that’s something I never even thought of,” Nwadike explained. “Only now when my brothers and sisters talk about how we went through some serious things when we were young.”

Another way to confront his trauma was to encourage police to be understanding of people’s fear.

“When I’m brought in for workshops, I remind police officers to have compassion,” Nwadike explained. “People aren’t always running because they’re trying to resist or have committed a crime. Sometimes they’re just scared, they’ve seen videos on the news and think they’re next.”

Nwadike explained how “the talk” in the Black community is when parents tell their children how to be extra cautious when interacting with police. He mentioned police shooting cases where the victim was facing mental health issues or made the wrong move and were shot by police.

Not only did Nwadike work through his own trauma, but he had the courage to protect others during riots. Between tear gas and bricks being thrown at the front lines, Nwadike stood as a peacemaker, with two of his brothers and other activists. All he had was a “Free Hugs” t-shirt, while riot police around him wore bullet-proof vests.

Two years after the Boston Marathon and his fame with the Free Hugs Project, the 2016 shooting of Keith Scott caused an eruption of protests in Charlotte, North Carolina. In this divisive time, Nwadike’s message of free hugs, to have peaceful communication, was ignored.

“I made a commitment that I’ll stand in the center to create that dialogue. Not as a point of neutrality, because sometimes being neutral actually gives strength to the oppressor,” Nwadike said. “Rather than feeling neutral, I could be here to help us move forward.”

As Nwadike stood between protestors and the line of riot police, he heard one officer ask for a hug. Nwadike embraced the police officer, even knowing the protestors would feel betrayed and begin harassing him.

“The best way to handle the situation was to stay and talk to the protestors and teach them the point of unity and heal the community,” Nwadike said.

His message spread through the crowd of protestors, who recognized him and respected his peaceful purpose. Nwadike told them how he witnessed the Los Angeles riots as a boy, and it was difficult for the community to recover after grocery stores and public places were destroyed.

“Being there that night [at the Charlotte riots], I understood all my experiences leading up to this point.” Nwadike stated. “As history repeats itself, acts of injustice lead to protests and riots. If there aren’t people on the frontlines with messages of unity, these things are just going to keep happening.”

He concluded that his form of activism was love, which reflected past civil rights leaders. When he saw a COD student wearing a Black Panthers jacket, Nwadike mentioned a conversation he had with Bobby Seale about the legacy of the Panthers. They talked about the free breakfast programs, having their own ambulances, and other community protection goals.

“I loved that. We were operating with love for our community. They were some of the greatest activists of our time, and even they were like, it was love, we were trying to heal,” Nwadike reflected.

Nwadike hoped to teach this diverse audience at COD how important love is in activism spaces. They need to support each other to overcome struggles, as student organizations and beyond. Even doing something as small as offering people a hug could make a huge impact.

To learn more about Nwadike’s work and recent projects, head to the Free Hugs Project website.

Zohaib Quadri • Feb 21, 2023 at 9:32 am

Love and affection is definitely the best form of therapy and stress relief!! We need to campaign for an initiative called Free Hugs Friday!

Mariyam Syed • Feb 23, 2023 at 11:00 am

Thank you for reading, Zohaib! True, it’s so powerful that hugs convey personal connection, and also solidarity.