Don’t Cross the Picket Line

The president and lead negotiator of College of DuPage Faculty Association weigh in on their reactions to the University of Illinois at Chicago United Faculty’s recent strike along with their expectations for their own negotiations beginning in February.

January 29, 2023

Imagine yourself, as a college student, driving to school on your first day of the second week of classes. You arrive on campus and see faculty, bundled up in their winter coats, scarves and gloves, swarming the building where you typically attend class. Managing to maneuver your way around picket signs, you make your way to the front of the crowd. Although you are now standing at the front of the entrance, a message written at your feet between you and a line drawn on the sidewalk blocks your path. It warns, “YOU ARE NOW CROSSING A PICKET LINE.”

This is what a student would have seen at University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) on Jan. 17 when the UIC faculty union, UIC United Faculty, went on strike after 31 bargaining sessions. Although UIC dedicated almost $4.5 million to improving student mental health services during the 31st bargaining session – one of the major UIC faculty union’s goals – the economic differences between UIC and the UIC faculty union remained significant. As of Jan. 19, the UIC faculty union’s proposal for a three-year contract was $9.3 million more expensive than UIC’s four-year proposal.

The strike at UIC ended Jan. 23 right after midnight, just in time for Monday classes.

Missy Mouritsen, political science professor and lead negotiator of the College of DuPage Faculty Association (CODFA), kept up with the UIC faculty union’s strike along with several other members of the association.

“There’s a large part of the faculty that went to UIC. I went to UIC myself to get my doctorate,” Mouritsen says. “A lot of us are dialed in to what’s going on at UIC. But, also, we have so many students that transfer there. So it pays to pay attention and to be familiar with their programs.”

Given that they met with the UIC administrators more than 30 times over several months before Jan. 17, she believes the union exhausted all other options before resorting to a strike.

“[The UIC faculty union] did the best that they could in order to reach an agreement,” Mouritsen says. “So I think a lot of us were sympathetic to what’s going on over there because of our connections, because of the students but also because of what they were asking for.”

The UIC faculty union’s proposal sought a three-year contract entailing a $3,000 permanent salary increase (equivalent to a 2.24 percent raise for tenure-track faculty and a 3.6 percent raise for non-tenure-track faculty), additional annual salary increases of 17.25 percent over the three years and at least a 22 percent raise for non-tenure-track faculty and an 18.5 percent raise for tenure-track faculty in the first year of the contract. The faculty also wanted UIC to improve mental health services for students, although the university committed to doing so without associating their pledge to any particular contract.

This is in light of the COD faculty union negotiations with COD beginning Feb. 7 preceding the end of their four-year contract on May 31.

Although Mouritsen admires the UIC faculty union’s impeccable organization, she does not draw too many other similarities between UIC’s strike and the potential for a strike at COD.

“We are different in that the problem at UIC is the decrease in funding from the state,” Mouritsen says. “I think our issues are different from their issues.”

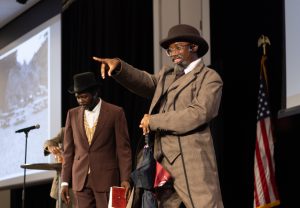

David Goldberg, political science professor and president of the COD Faculty Association, explained the goals the COD faculty want to work toward in its new contract.

“I want to continue on the improvements we made in 2019,” Goldberg says. “We want to continue with the advantages that we got there. For example, we now have department chairs. We didn’t have [them] before. But I think empowering faculty is the biggest thing that I would say, having the administration do what they can to help faculty do a better job and meet the needs of our students, increase the resources that are necessary for them. So that does mean that we need benefits and salaries that are competitive against 6.8 percent inflation.”

COD’s previous contract from 2019, which the association originally wished to extend, gave full-time faculty raises of 2.4 percent during the first year, 2.3 percent during the second year, and 2.0 percent during the third and fourth years. These increases were in addition to annual increases within each of the five individual salary ranges.

Despite the importance of the issues at hand, given that a strike requires professors to protest without pay and students to stay out of the classroom, Mouritsen views striking as a last resort. Both Goldberg and Mouritsen hope COD will not have to go on strike.

“We feel that we’re in a really good position, and that we will have public support on our side,” Goldberg explained. “COD has a really good reputation in the community. We’re negotiating, in my mind, from a position of strength. And I hope that means that we can resolve this in a way that benefits everybody who has good working conditions. And that as a result, we won’t have to go on strike.”

Going into the summer and fall, Mouritsen wants students to know the faculty will do everything they can to avoid a strike. However, if they must strike, they are doing so over issues fundamental to their contract that will help make sure students have the best possible experience.

Goldberg wants to assure students that the faculty are professionals and will try to keep what’s going on with the strike separate from the classroom as much as possible, but they will continue to communicate with students in the event of a strike.