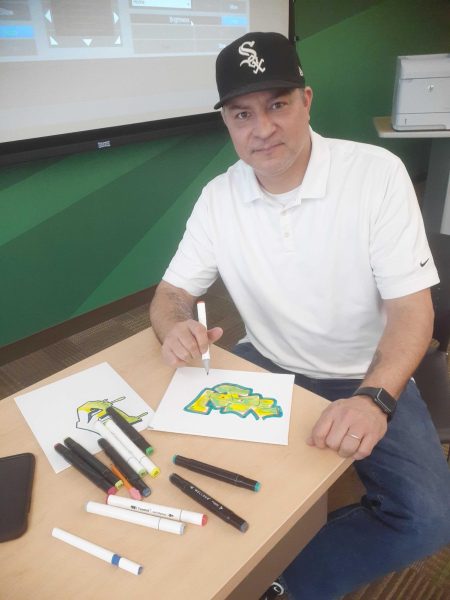

With the low rhythm of 1990s rap in the background, students colored unique works of art with ink markers on small canvases as part of COD’s fourth annual hip-hop summit. Devin Chambers, a COD counselor and co-adviser of the Black Student Alliance described how professional graffiti artist John Maeda led COD students in a workshop for the third time.

“We like that it’s a mix of educational, learn about the history of graffiti, how it came about, history of hip-hop in Chicago, plus helping students to develop their own style of graffiti,” Chambers said. “It’s very open and free-flowing, and John is around to help students to develop their own craft, to be artistic.”

Maeda grew up in Chicago during the golden era of graffiti in the ‘90s with its significance as a youth subculture. Maeda said teens were drawn in by the community and freedom that came with it.

“It was some Puerto Rican kids that came from the island, and they were trying to figure out a way to get friends and hang out,” he said. “I know it doesn’t seem like an art form, but it’s our form of expression. It’s art to us, and it has grown to be part of the art world.”

Sati Holloway is a student who attended the graffiti workshop with peers from the Intercultural Student Hub and Black Student Alliance. As an artist, the workshop inspired them.

“I thought it was a really good way for me to personally push my art past its usual boundaries and create something that feels really unique,” Holloway said. “I’ve always admired the way graffiti looks and have wondered on multiple occasions how one develops the skill for the intricate lettering or vibrant use of color in many pieces.”

These intricacies of graffiti art style were one aspect Maeda discussed, with the development of graffiti writing from small, impromptu scribblings to large, detailed and colorful murals.

“It’s part of growth in the culture,” Maeda explained. “Piecing, that’s our word for murals. Bombing or tagging, that’s putting your name on everything. The next thing we do was your throw-ups, your bubble letters or your readable style. If you were a piecer, you were hardcore. It took a lot of time; it took a lot of effort. As graffiti writers star to progress, we would take that letter and flip it. We’d add a lil design to it, a little drip, a little spike, or some different shadowing, and it would become yours.”

These artistic techniques were interesting to Divine Nkanga, as co-founder of the Divine Art Creators Club at COD.

“I just wanted to learn more about different art mediums because as DAC president, I have to explore different mediums, so I can cater the best to the art students or artists who are out there, who have different skill sets,” Nkanga said. “I really appreciate all mediums of art, even the ones I don’t really have the hang of. What brought me here, I just wanted to do something fun with my friends.”

This social aspect also resonates with the birth of graffiti. Maeda described how the appeal of graffiti was not only the art, but to build a social reputation through your artistic talent being seen by your peers and the wider world, at a time when there were not many outlets.

A 2011 PBS article describes how the first modern graffiti artist is widely considered to be Darryl McCray, who in 1967 spray painted a message of love to his crush on walls around his city. This story and other similar ones of the era are indicative that more than anything, graffiti was a form of social communication.

Maeda described how this captures the essence of graffiti as a form of expression and social building beyond mere rebellion. In Maeda’s own life, he met his wife through graffiti artist circles as a teen.

“Just so happens, 30 years later, I’m married to the hottest, most up graffiti-writer girls in the entire city. Now we’ve both got kids and married since then,” Maeda said. “Story in the making. The girls that were doing graffiti, they also got the dopest graffiti writer. So there was outside of the fame, there was some gold at the end of the rainbow. ”

Along with this social aspect, the underground, risky nature of graffiti drew even more appeal to adventure-seeking teens.

“When you’re in the train yard, and it’s illegal, and it’s two o’clock in the morning, so you got trespassing,” Maeda described. “Then you got graffiti, which in the ‘90s became a felony, and you got possession of spray paint that was also a felony, you can’t sell spray paint in Chicago.”

This criminalized nature of graffiti, to the extent that it was a jailable felony, stemmed in part from the use of graffiti by young gang members. However, it also led to the overcriminalization of many youth and stifled the artistic scene. Despite the negative social views of graffiti, Maeda described values that guided him and his peers.

“We never bombed somebody’s home. We never tagged on a church. We never tagged over somebody’s real art,” Maeda said. “But as it has progressed, those values have kind of become lesser and lesser. People have a lack of respect for the true art form, instead with, ‘I’m a vandal, and this what I do.’ Everybody’s gonna renegade, but there are still some old school crews that teach respect.”

Holloway addressed this aspect of graffiti and why it is an important art form despite how people approach it.

“I think that the essence that really makes graffiti its own art form and expressive medium is the risk and sort of rebellion that comes with the act of leaving your mark on a public space,” Holloway said. “There’s a certain level of confidence one has to have when even writing your name on the side of a train, and that’s pretty admirable to me. It’s such a beautiful way of proving your existence, and it makes me sort of sad when you see it portrayed as something totally criminal. To use art to prove that something as little as your name is worth displaying is seriously impressive, and I wish for myself and most other artists to exude that same kind of confidence going forward in our lives.”

With this mindset, many young graffiti artists developed career paths, such as Maeda’s friend Max Sansing, who became a renowned artist commissioned worldwide for his hyper-realistic murals. Maeda described how graffiti became mainstream and acceptable as an art form, with companies contracting graffiti artists for murals, art galleries, advertisements, commercial shoots and social media campaigns.

“In the ‘90s there was one graffiti writer in particular named Design that had this idea. He wanted to leave the ghetto and use this medium as his way out. Just like hooping, or any other victory story coming out of the hood,” Maeda said. “Fast forward. Design leaves the hood. He’s the first one in Chicago getting commissioned by Pepsi and all these major companies to do logos.”

In a similar vein, COD artists and fashion design students expressed their creativity during the hip-hop summit at an event about how hip-hop influenced fashion trends in America and the world, especially through the ‘80s and early 2000s. The event featured an outfit designed and sewn by fashion studies students.

Students are invited to attend the Fashion Show on May 11 as either model dressers or audience members. Students can also participate in the Hip-Hop Festival Open Mic Competition on May 8 for a chance to win scholarship prizes starting at $1,400.