Bourdain, Spade suicides show how even those at the top can know the lows of depression

June 11, 2018

Bourdain, Spade suicides show how even those at the top can know the lows of depression

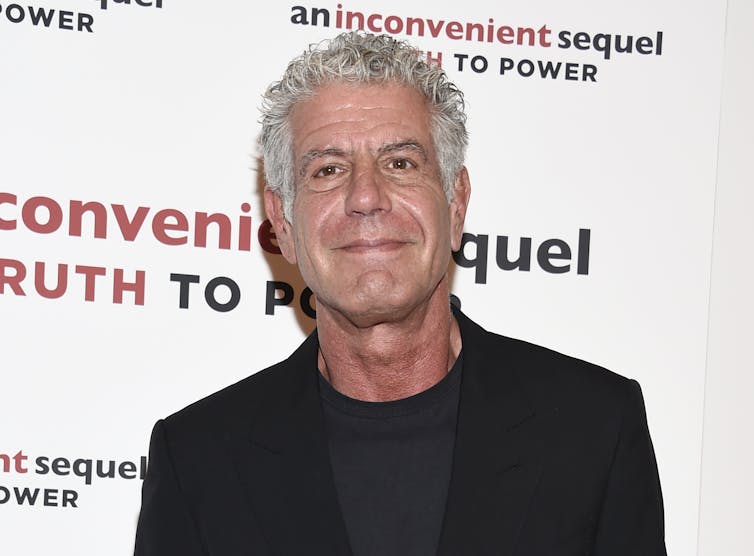

Evan Agostin/Invision/AP Photos

We struggle to comprehend the loss of Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain. Sudden deaths are shocking. It’s doubly shocking when the deaths are by suicide. Sudden suicide by people who seemingly have it all: That’s a triple whammy.

Of course, as humans, we try to make sense of it all. We say depression and suicide can strike anyone. We cite U.S. statistics of a sharply rising toll of depression and suicide. We point out that what a person shows on the outside can mask deep pain on the inside.

These explanations are true as far as they go. They just don’t go very far. And they dodge the most nagging question: Shouldn’t having great money, fame, and power insulate a person from severe depression?

As a psychologist who spent years researching the origins of the contemporary depression epidemic and writing a book on that topic, my answer is no. While money can summon therapists, fame can bring admirers, and power can remove many mundane hardships, none of these resources turn off the fundamental psychological drivers of depression in Western societies.

Carrots and Camaros

A first driver goes by the fancy name of hedonic adaptation, which basically means that pleasures inevitably fade. This process flows from evolutionary imperatives to survive and reproduce. Bunnies are built to seek carrots. Pleasure rewards the bunny for finding the carrot. But the satisfaction cannot last. It’s only the end of pleasure and the promise of more that gets the bunny hopping off to find more carrots and ultimately to survive long enough to make more bunnies.

So, too, humans restlessly seek power, fame and money in a race to survive and reproduce. Intuitively, we think the pleasure of having a billion dollars, living in a castle, or having servants should never fade. In reality, all fade as reliably as a good carrot. The wealthy, famous and powerful may fight harder to stave off hedonic adaptation, but data show such efforts are basically futile. Whether you buy one fancy sports car, or 10 of them, any boost to mood quickly subsides.

The mirage of pleasure

Seeking rewards may be natural, but when it comes to the moods we want, millions seek a mirage. Hedonic adaptation cruelly mandates that intense pleasures will not last, at the same moment survey data show Westerners are seeking these states. Hence, there’s a yawning gap between what we want to feel and what we actually feel – a chronic dissatisfaction that breeds depression. In fact, there is evidence that the people who value happiness the most are actually the most depressed.

Are the famous, rich and powerful immune from unrealistic mood standards? No. If anything, people who have “everything” on paper should be even more tempted to ask the question “Why am I not happier?” and set out to grasp an unattainable mood.

NadyaEugene/Shutterstock.com

The widespread use of social media outlets like Facebook and Instagram may be adding social pressure not only to experience unrealistic mood states but also to project these mood states outwardly. The new psychological race to keep up with the Joneses is relentlessly documenting the bliss from fancy vacations, newly acquired possessions, and parties with friends, with the rest of life largely edited out. Perhaps not surprisingly, constantly referencing other people’s highlight reels on social media is associated with depression.

People with money, fame or power cannot easily avoid being swept up in the process of constant upward social comparison. People who “have it all” can become trapped in their own social media webs. Living up to a carefully curated image of a perfect life may bring with it greater pressure to conceal depression, and to push away the support that comes from admitting vulnerability. Social media bubbles burst only when it is too late.

For sure, being rich, powerful and famous has its perks, including preferred access to mental health care. Generally, people in such favored positions don’t wish to swap places with the poor, weak and obscure. That said, the core psychological processes that are breeding depression and suicide in the U.S. are penetrating every ZIP code. At present, no one gets to opt out.

Having an explanation is not the same as solace. In this case, I believe understanding the bigger picture is more unnerving than it is soothing. Because if those at the top of the social pyramid are subject to universal processes at work in an escalating epidemic of depression and suicide, our society can expect that more Spades and Bourdains are yet to come. I hope we will take their deaths as a urgent call, and marshal a more robust public health response to these twin epidemics. And I hope we never become inured to the shock if we do not.

![]() If you are having thoughts of suicide, please know that you are not alone. If you are in danger of acting on suicidal thoughts, call 911. For support and resources, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or text 741-741 for the Crisis Text Line.

If you are having thoughts of suicide, please know that you are not alone. If you are in danger of acting on suicidal thoughts, call 911. For support and resources, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or text 741-741 for the Crisis Text Line.

Jonathan Rottenberg, Professor of Psychology, University of South Florida

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.