A Parallel, Altered World in “White Noise”

“White Noise” presents a reality that’s both familiar and unfamiliar, and provides insightful and funny commentary on our lives.

March 13, 2023

“Car crashes are a celebration… an event of optimism,” Professor Murray (Don Cheadle) at the College-on-a-Hill says to his class. “Look past the violence. There is a wonderful brimming spirit of innocence… and fun!” This is one of the opening lines of “White Noise” that establishes the ironic treatment of American media during the movie’s runtime. I appreciated the insightful and witty nature of the dialogue, but the rest of the movie felt like a vehicle for the script.

The film begins with the first chapter, “Waves and Radiation.” We’re taken to the office of another professor, Jack Gladney (Adam Driver), our main character with the peculiar job as head of Hitler studies at the college. That is, Jack studies Hitler as a biographer would. According to Jack, he started the program decades ago and since then it’s been a “hit.”

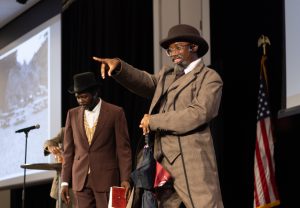

It’s the start of the school year, and once Jack is home, we’re introduced to his wife, Babette (Greta Gerwig), and their kids: Heinrich (Sam Nivola), Denise (Raffey Cassidy), Wilder (Henry Moore) and Steffie (May Nivola). Denise, in the midst of a kerfuffle in the kitchen, sees Babette swallow a pill. But, Denise thinks, Babette doesn’t take anything, or at least she shouldn’t be. Later, to give some credence to the Elvis lecture that Murray is doing, Gladney does an unawarely-absurd co-lecture with Murray, drawing connections between the childhoods of Elvis and Hitler. It’s at this time that a train, carrying toxic chemicals, is rammed into by a truck carrying much the same, thus creating a toxic cloud. Slowly gaining speed, the cloud soon reaches Gladney’s house, and they’re forced to leave in a national emergency, beginning the second chapter of the story, “The Airborne Toxic Event.”

Jack, as head of Hitler studies, is embarrassed that he doesn’t speak German. This may seem like a throw-away punch-line, but the movie presses on with jokes such as these, illustrating the pointless and ridiculous nature of what we accept and do. Devices such as these are something I loved about the movie. A similarly-natured joke is when Babette’s venting to Jack about how she sees her life, beginning with:

“My life is either/or. Either I chew regular gum or chew sugarless gum, either I chew gum or I smoke, either I smoke or I gain weight, either I gain weight or I run up the stadium steps.”

“Sounds like a boring life,” Jack dryly comments.

“I hope it lasts forever,” Babette wishes.

An ever-present element of the movie I enjoyed is the sardonic air with which the characters talk to each other and behave, as if they’re constantly talking past each other. It feels like a continuous “Tim and Eric” bit where the people in this world are rarely ever aware of how ridiculous, non-human and unnatural the way they speak is.

Another part I liked was the philosophical quality to much of what they say, too. Within a seemingly ordinary conversation, characters exchange critiques on society, how we view our surroundings and experiences, including death. One exchange caught me by surprise at the beginning of the film where Babette notes, “I have trouble imagining death at that income level.”

“Maybe there’s no death as we know it, just documents changing hands,” Jack wonders.

The Gladney’s kids have similar dialogues, the first of which begins with Steffie asking:

“How do astronauts float?”

“They’re lighter than air,” Denise suggests. “There is no air,” Heinrich responds. “They can’t be lighter than something that isn’t there.”

It’s conversations such as this one that lead nowhere, but take the audience on a journey of confusion and misinterpretation, wondering where one idea joins to the next, so it seems that they’re constantly talking past and misunderstanding one another.

A second example of this begins with Denise saying, “It’s called the sun’s corolla. We saw it on the Weather Network.”

“I thought Corolla was a car,” Steffie blurts.

“Everything’s a car,” Heinrich replies. Seemingly every character, throughout the movie, offers some commentary about modern life of the same nature as what Heinrich said.

Transitioning between scenes is done well, taking for example one moment where Jack asks, while in bed with Babette, who’s out there looking up at the fading lights from outside reflecting on his ceiling. The camera then faces outside, with that light seeping in through the blinds. Meanwhile, the soundtrack, a somber piano melody slowly fades into the chant of a Nazi march, at which point it cuts to one of these marches, which Jack is showing in his class. The dark lighting and soundtrack make for a good transition to such unsettling imagery.

Another great transition that also takes place in Jack and Babette’s bed is when a stranger, who’s only shown silhouetted, gets into the bed alone with Jack. The stranger then get under the sheets, cover silhouetted face, and slowly moves towards Jack, who gives a mortified expression the whole time, until the camera closes in on the face, at which point the covers are taken off and it’s revealed to be Jack’s face, exasperated, just waking up from a nightmare. For one, the suspense is at its height when we see the stranger close-in on Jack’s face, and Jack’s face being revealed is an inventive and surprising way to bring the audience out of a tense scene.

The movie’s plot is logical, in that one event clearly leads into another, and it’s explained to the audience how this happens. While narrating that the toxic cloud lasted more than a week and was then eaten by microorganisms, Murray says this directly, and then brings up Babette’s addiction to a mysterious drug known as Dylar that Jack nor Denise can find the source of.

Breaking the movie into chapters was a good way to sequence it into a more sensible flow that might’ve been otherwise confusing to most viewers.

Considering what I’ve said about the film’s script, nearly every item and person in it is a device in terms of conveying a deeper meaning. One that was on-the-nose was the grocery store featuring a wall that was entirely a close-up of bright-red meat. That, as well as the repetition of the items where every aisle seems to go on forever like the symmetry created when you face two mirrors at each other, and every item is perfectly placed. The store was what we imagine when we think of a grocery store, too clean with lighting that’s fluorescent and unsettlingly omnipresent. Secondly, the deadly cloud that forms results in Jack developing a chance of dying. This doesn’t seem alarming, and isn’t. But, Jack and Babette think it is, and it results in a whole chapter, “Dylarama,” in which he faces the chance of death and his wife’s addiction to Dylar, a drug that supposedly prevents the fear of death.

From the didactic script to the bizarre storyline, “White Noise” felt like a refreshing break from what I’ve been watching for the past month. It’s a Netflix original, so it’ll be on there for the foreseeable future. 4/5