White people: Is it OK to hate us?

September 8, 2018

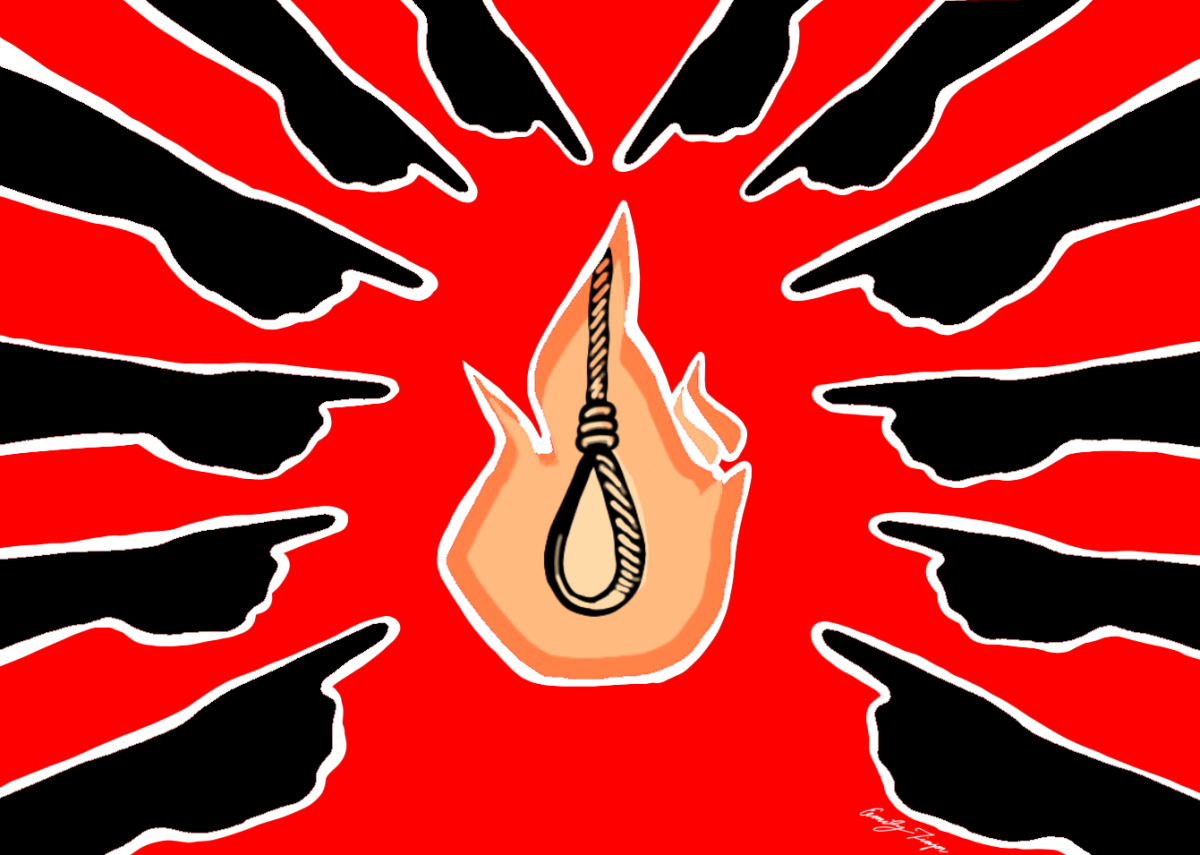

In an era when cultural divisiveness is at its peak, we are being re-exposed to the racism, sexism and discrimination that minority groups have been struggling with for time immemorial. Black Lives Matter, the “Me Too” movement and anti-immigrant vitriol infesting our politics have all reminded us of the work that still needs to be done to ensure true equality can one day be obtained.

But equality is a funny thing. It can often feel like no one actually knows what it really means. Everyone has a different perception of where the goal is.

When Sarah Jeong, a newly hired technology writer for the New York Times, had “anti-white” tweets uncovered by an anonymous Twitter user, conservatives and right-wing pundits were outraged by the hypocrisy.

“#CancelWhitePeople,” Jeong wrote in a tweet. “Oh man it’s kind of sick how much joy I get out of being cruel to old white men,” she wrote in another.

Which begs a fine question: Is it OK to make hateful comments about a generalized group, if that group is “white people?” Are white people the only ones left who it is still acceptable to hate?

Jeong responded to the backlash by apologizing while also defending her posts as satirical reactions to those who harassed her.

“I mimicked the language of my harassers,” Jeong said in a Twitter post.

Whether this argument is a reasonable defense or not does not resolve the larger question. Is it still OK to make hurtful comments about white people, even if it is meant in jest.

The best defense is that white people are not and never have been oppressed or marginalized. White people have never been without power. Some believe racism is a concept imbedded within the framework of institutionalized power and historical context. Nolan L. Cabrera, an associate professor at the University of Arizona who is writing a book on racial attitudes amongst white students, told the Washington Post whiteness is not the same as other racial identities.

“The term ‘racism’ is not the equivalence of prejudice or bigotry,” Cabrera said. “It’s an analysis of social inequality along color lines and an analysis of power dynamics and social oppression. None of which has ever been in the hands of people of color or communities of color.”

Despite a reasonable analysis of racial power dynamics, this statement ignores the reality that many are not trying to equate racism with oppression.

Which brings me back to a major issue within this debate – the multiple perceptions of equality and race, held by different groups. If those in minority communities and those in white communities have different definitions of racism, conflicts such as this are bound to continue.

The idea that racism and oppression are one and the same is conflation. Those without power can be racist. Those without power can hate those with power. That hate, when based solely on skin color or nationality, is racism. The social and political power structures that govern American society are not manipulated by individual members of minority groups to systematically discriminate against the white majority. However, whether an individual has the power to discriminate or oppress those they hate based on race is not a requirement for the things that person believes to still be considered racist.

In 2009, David Pilgrim, the curator of the Jim Crow Museum, responded to a question about anti-white racism in an open online forum held by Ferris State University. Pilgrim discussed the many definitions of racism and argued, depending on the definition held, hateful behavior exhibited by a minority can be categorized as racist.

“If you define it as “prejudice against or hatred toward another race,” then the answer is yes,” Pilgrim said, when asked if African Americans can be racist. “However, if you define racism as “a system of group privilege by those who have a disproportionate share of society’s power, prestige, property, and privilege,” then the answer is no.”

Pilgrim argues individual members of minority groups can exhibit racist behavior, hold racist beliefs or even sometimes be defined as racist. However, as a collective group, minorities are neither creating nor benefiting from the systemic racism permeating American social and political constructs.

Jeong’s tweets were targeted at a generalized group of people, based on skin color, and regardless of intention, the language was hateful.

The most egregious tweet, in my own opinion, was one that reiterated a point I frequently see argued online. There is an attempt to exclude the voices and opinions of white individuals who wish to contribute to discussions about race or culture.

“White people marking up the internet with their opinions like dogs pissing on fire hydrants,” Jeong tweeted.

Often referred to as “whitesplaining,” white individuals sharing opinions online can find themselves rebuked or told to “stay in their lane.” Although not all ideas shared by white people online may be constructive, censoring the voices of an entire race, even as a response to centuries of minority censorship, does nothing to heal divides or build healthy diverse communities. Labeling expression from those you disagree with or do not want to hear from as “whitesplaining” or “mansplaining,” is just a new way to stifle speech.

In a New York Times Op-Ed, Thomas Chatterton Williams wrote about the silencing of white voices as a by-product of new “left-of-center public thinking,” when discussing the politics of race.

“Whiteness and wrongness have become interchangeable — the high ground is now accessible only by way of “allyship,” which is to say silence and total repentance,” Chatterton Williams wrote.

Any generalization of a group that leads to the silencing of all voices within it, is imprecision. It presumes to know things about an individual or their perceived identity based on nothing but the color of their skin. To some, this is the definition of racism they prescribe to and the definition does not limit itself to minorities. Assuming that a man explaining something or a white person sharing an opinion is immediately done so with intent to assert authority over the ideas of others within the context of a power dynamic, is a generalization that can be considered racist or sexist.

Of course, there is a clear and significant difference between systemic racism, which has permeated our political infrastructure, defined public policy for centuries and resulted in the systematic discrimination of a group of people based on race, and one individual saying something hateful about another individual or group.

Despite the obvious impactful differences, both actions can be defined as racist and neither should be acceptable.

Responding in kind to what you see as oppression from a white majority does not resolve anything and only fuels perpetual division and conflict. No room is left for a resolution. The dynamic becomes one of winners and losers.

This is not the way you coexist, and it is only encouraging those in extreme groups who thrive on their perceived victimhood despite a more privileged racial or gendered status. White supremacy feeds off of divisive rhetoric and the manufacture of cultural and racial “wars.” Language that can be defined as “anti-white” serves to legitimize their belief that white identity and culture is under threat, despite all evidence to the contrary.

Not only is it possible for minority groups to hold and express racist views about white people, it is also done so to their own detriment, fueling the backlash from white extremists groups who fight against what they perceive as their own cultural demise.

When I reflect upon my own reaction to Jeong’s tweets, I freely acknowledge that the differences between “anti-white” rhetoric and systemic racism, discrimination and oppression are palpable. Jeong’s words had no impact upon my sense of self as a white American, and like water off a duck’s back the words lacked any sting. My response to her tweet was not one of concern for those white individuals who may choose to be affected by the words used, but of concern for the larger social and cultural implications of continued racial division in American society.

While writers for left-of-center publications like Vice News and Huffington Post argue “reverse-racism” isn’t real, a National Public Radio (NPR) poll from October, 2017 found a majority of white Americans believed they faced discrimination.

“More than half of whites — 55 percent — surveyed say that, generally speaking, they believe there is discrimination against white people in America today.”

Regardless of how an individual defines racism, it is clear that continued racial division and animosity is not the solution when the perception some white people have of being persecuted may define their politics and beliefs.

Chatterton Williams argued in his Op-Ed that a continued focus on the foundations of America as rooted in white supremacy continues to give whiteness power and “exacerbates inequality.” By analyzing the writings of prominent African American author Ta-Nehisi Coates, as well as the racist speech of white nationalist, Richard Spencer, Chatterton Williams noted a problematic connection.

“Both sides eagerly reduce people to abstract color categories, all the while feeding off of and legitimizing each other,” Chatterton Williams wrote. “Both sides mystify racial identity, interpreting it as something fixed, determinative and almost supernatural.”

“What identitarians like Mr. Spencer have grasped, and what ostensibly anti-racist thinkers like Mr. Coates have lost sight of, is the fact that so long as we fetishize race, we ensure that we will never be rid of the hierarchies it imposes. We will all be doomed to stalk our separate paths.”

No matter your personal definition of racism and despite the evident history of systemic prejudice and minority oppression, a progressive movement towards equality cannot allow for the condoning of any hateful speech against any group. It is not OK to hate white people for their race alone. A unified, diverse and truly equal America will not allow for it.