Students Lead Social Change in Africa

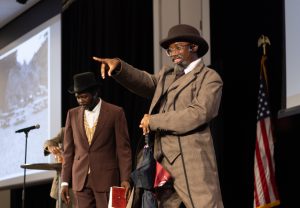

As part of the Living Leadership program, COD students communicated with activists from two contemporary African social movements, #FeesMustFall and #ThisFlag.

November 21, 2022

Balancing the duties of being a college student and the leader of a social movement has been a challenge for African activists. Over the course of two virtual meetings, South African and Zimbabwean students and activists shared their experiences with COD students.

South African activist, Oratile Thotela, described the pressures of taking a leadership role in the #FeesMustFall movement, while also attending the University of Cape Town as a student.

“It’s quite a taxing environment because you give yourself as the leader of the movement and serve in any capacity you can,” she said. “You even go beyond that to do the job of institutions, do the right thing that isn’t being done by those in power. That was a big thing for me to balance.”

Thotela and fellow students specifically dealt with the tuition fees that were rapidly increasing every school year, while the universities themselves were under-resourced. For example, some students didn’t get dorms and would have to sleep in classrooms, described one of the South African participants in the exchange meeting. Even facing these challenges in getting an education, the South African students still had to organize for change in the system.

In 2015, 5,000 protestors from universities in Cape Town gathered at a South African Parliament meeting, demanding that the yearly tuition increase be halted. After two years of protests and universities being temporarily shut down over these, the #FeesMustFall movement achieved its first solid outcome.

The Higher Education Minister Blade Nzimande implemented a 7% tuition increase cap for that school year. They also widened the income bracket for students to receive grants. It went from R120,000 to R350,000, which accommodated more working-class people.

According to the activists in the exchange, this was still far from the main goals of the movement, which was seeking more systemic changes for academic institutions in the nation.

“Our movement incorporated the idea of being a change agent to make institutions of higher learning inclusive to everybody, that includes all stakeholders of the institution.” Thotela described. This meant more equitable academic systems to minority students, like those in lower socioeconomic spheres. Even the college faculty members who worked in more menial, lower-management jobs joined the #FeesMustFall movement.

“The initial issue that we’re still dealing with was institutions that alienate people of color, the very people that are getting the education to give back and participate in the economy,” Thotela explained. She explained this to be a result of the historic apartheid system.

Similar systemic issues were also addressed by the Zimbabwe #ThisFlag movement. Zimbabwean activist Nyasha Musandu described how during that time in Zimbabwe, citizens were losing economic security. It was exacerbated by an authoritarian government under President Robert Mugabe who held office for 37 years.

“We had gone through a period of hyperinflation after 2008, and it was a really tough time in our history,” Musandu described. “By 2016, we are really experiencing the last days of a dictator, though we didn’t know it at the time.”

It all came together when a Zimbabwean pastor named Evan Mawarire posted a video on social media in October 2016. He described the difficulties he faced in paying school fees and providing basic necessities for his children. It was a common situation for many families in Zimbabwe at that time, and the message spread quickly online with the hashtag #ThisFlag.

In the video, he held up the Zimbabwean flag and described how after independence in 1980, the flag represented the self-determination of African people. Despite power being transferred to them, there was still a sense that people weren’t free and secure.

“Given Robert Mugabe’s regime and the corruption in the country, the flag no longer meant anything to anyone. The flag had been appropriated as a party symbol rather than a national symbol,” Musandu stated.

After Mawarire’s video, people began wrapping the Zimbabwe flag around themselves when they went out in public for daily activities or to rallies. Alongside about 9 million Zimbabwe citizens, Musandu was inspired to join the movement. She became a local leader for the #ThisFlag protestors in her area by helping the movement speak to the government about its demands and message. Their rallying cry both on social media and during protests was “Hatichada” meaning “we’ve had enough” in Shona.

One of the first real demands of the #ThisFlag movement was about restoring economic security through government actions.

“We had a debate with the Reserve Bank for bond notes about where the money was really coming from,” Musandu said. Many feared that introducing a new currency would not actually solve the root of the economic problems- government corruption.

One of the Zimbabwean participants of the global exchange program, Nyasha Savala, was a teen when she first observed the protests. She connected it to her own life experiences seeing wealth disparity. Her classmates who were in families of government officials were better off than average citizens. Politicians misappropriated government funds for personal uses, while public infrastructure was failing, even in the national capital of Harare.

“How do you look at it when you have a lack of resources in the country, power outages for sometimes 14 hours? There was loadshedding in the winter,” Savala described. “Even during COVID, some people would rather stay home and hope to heal through their home treatments rather than go to a hospital.”

The most scarring occurrence was when a group of infants in a government hospital passed away because their incubators turned off in an outage. Musandu said this event fueled people’s anger and proved, in their view, that corruption kills.

As people protested more intensely, the government counteracted them. Musandu showed images of herself and her husband, along with fellow protestors being arrested by riot police. Many of the leading protestors were put in prison or made to pay large fines. Eventually, Mawarire whose video kicked off the movement was also arrested.

“There was a beautiful moment, and also one of the turning points, upon his arrest citizens gathered outside the court, hundreds and hundreds of citizens,” Musandu said.

Despite the unity and vast mobilization of protesting citizens, Musandu described how the movement became ineffective in achieving its goals. The main issue was that as a citizen’s movement, it needed more power to make systematic changes in the government.

“We realized the painful lesson that movements themselves can capture the imagination of the public, but they can fail to transform the systems itself, in terms of political change,” Musandu explained. “If we do not change the political landscape, we don’t have the power to actually change the issue.”

This message concluded the explanation of the #ThisFlag movement and the COD students and participants from African nations began dialogue between how they can adapt these lessons into contemporary social change movements.

The Living Leadership: Africa Exchange provides more information about the outcomes of the #ThisFlag and #FeesMustFall movements and the activists’ work. COD students can also contact Stephanie Quirk to participate in similar Living Leadership programs. Next spring, the exchange program will focus on international environmental issues.