OPINION: The dangerous message in telling low-income students to skip college

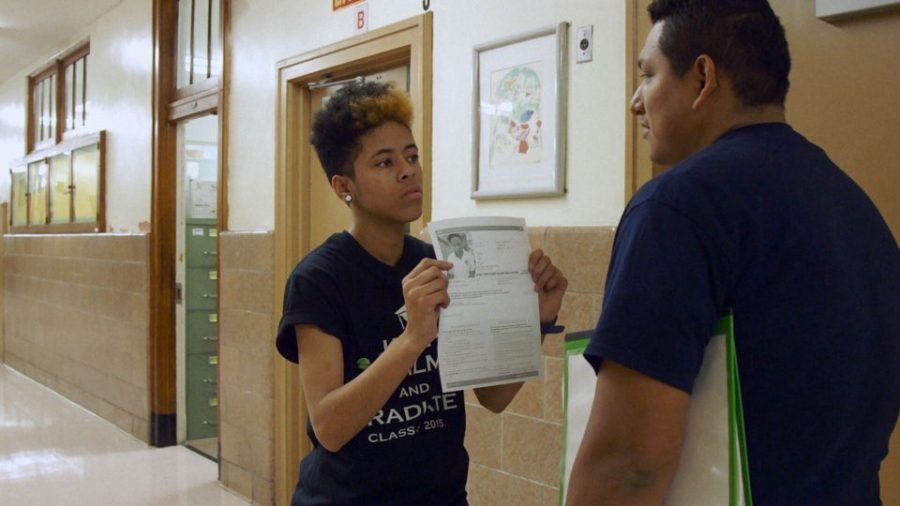

Karoline Jimenez finds a student to persuade him to take the SAT in the 2019 documentary Personal Statement.

June 4, 2019

When I was a teenager, I made a deal with my dad: I could join his paint crew, painting houses part-time, but only if I promised to go to college. My father was proud of his work, but he did not want house painting to be my only option. Like my mother, he hadn’t graduated from high school. They wanted more for their children.

A member of the paint crew later asked if I was going to join the team full-time after high school. When I told him I was going to college, the man scoffed at my ambition. “If a paintbrush fits in my hand,” he said, “it’ll fit in my son’s hand, too.”

But I kept my promise to my dad. So did my siblings. We became engineers, doctors and directors of nonprofits. I eventually earned a master’s degree from Harvard.

The message that college is “no longer worth it” is not only false but also dangerous for America’s low-income students. I was fortunate to have a village of adults telling me that college was worth it. Not all children are so lucky, with many coming from high schools with too few counselors and too little advice about which institutions to attend and the merits of a postsecondary degree.

Each day brings a new public opinion poll, op-ed or article questioning whether college is worth it. Fifty-seven percent of working-class voters in America now believe a college degree will “result in more debt and little likelihood of landing a good paying job.”

One recent survey found that less than half of Americans believe earning a four-year degree will lead to a good job and higher lifetime earnings. It is increasingly easy for families like mine to marshal statistics supporting that skepticism. About 40 percent of recent college graduates are underemployed, working in jobs that don’t require their level of skills. Almost half of students who start college never complete it, and many leave in debt.

Although such statistics raise legitimate concerns, they do not paint the full picture. On the whole, a college degree remains the surest bet for social and economic advancement. The economic returns of college are especially profound for low-income students, and yet they are far more susceptible to college avoidance than their more affluent peers, who are likely to go to college anyway.

Such views are hugely problematic for those of us hoping to improve economic mobility in the United States. Almost all the job and wage growth now goes to people with some form of postsecondary education. Many studies show that a four-year college graduate will earn between $500,000 and $1.2 million more over his or her lifetime than those with only high school diplomas, or those who dropped out of high school, like my own parents.

During the Great Recession, unemployment for high school graduates was substantially higher than it was for college graduates, and during the ensuing recovery virtually all of the new jobs went to college graduates. Those who’ve earned degrees also have a host of other positive outcomes, on average, including greater job safety, better overall health and longer lives. Societal benefits from higher education are substantial as well. College graduates are more likely to volunteer in their communities and, of course, increase the income tax base.

These factors, and many others, translate into better individual lives, more vibrant communities and a stronger country. Higher education not only helps America compete with the rest of the world but, perhaps most importantly, it also helps us reach our full potential as a nation.

But like most things, with this reward comes risk, and many students — low-income students in particular — are not well-informed about the best ways to select a college. Research shows that students do best when they enroll in the highest-quality schools that accept them, yet far too many low-income students fail to consider more selective colleges, “undermatching” into less demanding schools with significantly lower graduation rates.

Cost, of course, also can deter and intimidate low-income or first-generation students who have no direct experience with the benefits of college. And with the rising cost of tuition, a majority of students will likely need to take out some type of loan. A good rule of thumb is to avoid taking on more total loan debt for a four-year degree than one expects to earn annually after graduation. But assessing the total cost of college can be difficult because so many colleges offer “discounts” on their publicly stated tuition, and these are often poorly communicated to the public.

Sadly, each of these risks is magnified among low-income students. We must prioritize investments to help more low-income students and their families manage these increasingly complicated questions and challenges.

The biggest risk of the emerging view that college’s value is waning is that many students and families from the bottom 80 percent of the income distribution will stop looking to address the complicated questions and simply substitute the answer of “Don’t go.”

That’s neither good for them as individuals nor for us as a nation.

This story about the dangers of skipping college was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for our newsletter.

Jim McCorkell is founder and CEO of College Possible, leading strategic organizational development, engaging and building relationships with national partners, and championing the organization’s commitment to creating more college graduates.