Make war for art

April 6, 2016

Is there a better way to let your voice be heard than to put on a gorilla mask and go forth into the world?

The Guerrilla Girls don’t think so. These unapologetic, anonymous women have taken the issues of sexism and racism in the art world into their own hands. By incorporating humor with harsh statistics, the Guerrilla Girls have uncovered the secrets of museums and galleries to the public since 1985.

As a part of the Visiting Artists series, Columbia College Chicago’s curator Neysa Page-Lieberman spoke to students about her work with socially engaged art. Page-Lieberman defined socially engaged art as artists who work collaboratively with other artists or strangers through empathy and risk.

To illustrate this art form, Page-Lieberman told students about her close, in-depth work with the Guerrilla Girls; a group of artists dedicated to stopping art discrimination.

The Guerrilla Girls’ work immediately spoke to Page-Lieberman, who studied art through high school and college. She constantly found herself questioning why she wasn’t taught about non-white artists.

“When I first learned about the Guerrilla Girls, it was like I found my religion,” said Page-Lieberman. “It answered so many of my questions. These are people saying outside very loud what I was asking when I was young. I didn’t know there were legions of women through history creating art because their stories weren’t being told. I didn’t know as much about the non-white world. I was starting to uncover these histories, but it was work. To find any history outside the mainstream was hard work. And [the Guerrilla Girls] said there’s a reason for this; it’s called sexism, racism and exclusivity.”

The group’s first action of protest in 1985 were simple photocopied posters which read, “How many women had one-person exhibitions at NYC museums last year?” What followed this question was the sad answer of zero for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. The Museum of Modern Art had one exhibition.

“When they first put these posters up, they weren’t the Guerrilla Girls yet. They were a group of women with one or two male members who were just really pissed off about seeing this exclusivity in the art world that really privileged white, male, cisgendered artists,” said Page-Lieberman. “They decided someone has to say something: let’s put some posters up and see what happens.”

What happened because of these posters was more than imagined. An uproar began along with a media-frenzy. The group was filled with women artists and their harsh calling out of museums could result in backlash if the public knew their true identities. “Everyone was trying to figure out who did this, who was behind this,” said Page-Lieberman. “They started calling themselves the Guerrilla Girls, and they spelled it like guerrilla warfare. They decided as a pun in guerrilla warfare that they would dress as gorillas.”

The public’s response to these quiet protests proved that the issue of art prejudice was one that not enough people knew about. The Guerrilla Girls wanted more than to just represent the facts, they wanted tangible change to occur. They had to get more people aware and talking.

“After they first posted these general and indisputable facts, they decided that they were just going to make people angry, and at a certain point they would alienate themselves,” explained Page-Lieberman. “They had to incorporate something else, at one point they brought in humor. When they started being funny and people would laugh at it, they realized this would really open a lot of doors to meaningful dialogue.”

The straightforward statistics turned into head turning, witty commentary.

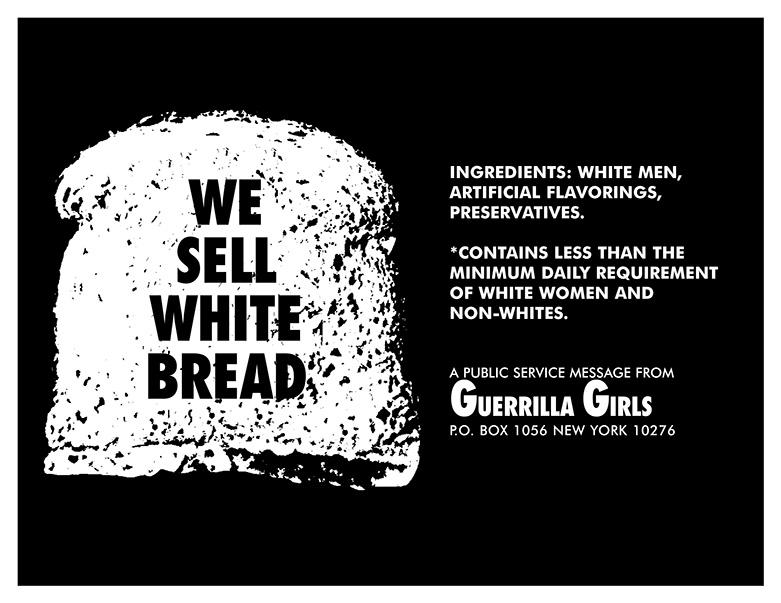

“Bus companies are more enlightened than NYC art galleries,” “We sell white bread! Ingredients: white men, artificial flavorings, preservatives. Contains less than minimum daily requirements of white women and non-whites.”

The Guerrilla Girls started to see the art world’s eyes open, and they started to see the public speaking up.

“When they came onto the scene there was an uproar,” said Page-Lieberman. “There was a lot of celebration of what they were saying; there was backlash. People revealed prejudices when asked to defend their decisions on artists they were collecting. People would come out and say they didn’t collect women artists because there weren’t any good ones. They began a very heated discussion.”

Where the Guerrilla Girls’ work really hammered down on museums was when they released their statistics about the Metropolitan Museum in New York City. These statistics read: “Do women need to be naked to get into the Met. Museum? Less than 5 percent of the artists in the Modern Art sections are women, but 85 percent of the nudes are female.”

The group would walk around museums and simply count to find their data. “This was the start of their ‘weenie count’ which they’re really notorious for now,” said Page-Lieberman. “How many women artists are on view now? How many artists of color are on view now? These statistics at the Met. have barely changed. A lot of the data was collected from what was posted online and going through the galleries. A lot of it wasn’t sneaky spy work, it was what is put in front of you.”

The Guerrilla Girls moved past New York City to Chicago. They were invited all over the US and all throughout Europe. The influence of the group hit Turkey, Ireland, Italy, Amsterdam and more. They proved that the sexism and racism didn’t end at the U.S. borders.

As the group was invited abroad for the majority of the first decade of the 2000s, their influence died down in the U.S. This is when Page-Lieberman took the task of showing Chicago the Guerrilla Girls were still very much alive.

“When I opened the show, they were assumed to come down from their heyday,” she said. “I did this show when they kind of fell off the radar, the art world’s radar. I was interested in showing they were still really relevant, making incredible work.”

Page-Lieberman curated a socially-engaged show at Columbia College Chicago which gave the Guerrilla Girls their notoriety back in the U.S. Opening in 2012, the show continues to tour through 2016. The show was a retrospective look at the impactful works of the Guerrilla Girls. It showed their very first posters up to their most recent works.

Their message and reinventing of feminism sparked something in people around the world.

“The Guerrilla Girls have a lot of groups who were created in the legacy and support of the girls,” said Page-Lieberman. “They’re next generation Guerrilla Girl groups. They see the models, how effective it was [and] their practices, and come up with other things that speaks to the next generation. They opened the floodgates and said it’s okay to do this. In fact, we have to do it. We should never be afraid. The more of us that voice our opinions, the more we see an inclusive telling of our history.”

Though they began 30 years ago, their message still rings loud.

“I don’t necessarily think it’s important everybody knows about [the Guerrilla Girls] in particular, but everybody should be aware of the issues they raise,” said Page-Lieberman. “Something I hear them say all the time is that we are cultural producers. We are those who choose what gets to be shown, written about, preserved for history. We have the responsibility to tell the entire story of our culture. What they do is encourage people to be critical. We are all subjective, we talk about what we think is important. If we all talk about the same things, a majority of the population is left out of the discussion. If they ever feel like there’s bias in museums or galleries or any kind of environment, they should speak up. The only way things change is when people complain.”

To see all of the Guerrilla Girls’ work and follow their touring installation, you can go to guerrillagirls.com

Smithc223 • Apr 8, 2016 at 8:15 am

I just like the valuable info you provide in your articles. I will bookmark your weblog and check once more here frequently. I am moderately sure I will be told lots of new stuff right right here! Best of luck for the following! kaefebeadkaagdde