“I Think We’re Alone Now” – Connections and Contradictions in Erin Washington’s Art

Erin Washington’s exhibit at the Cleve Carney Museum of Art is designed to make you think, laugh, then think again.

October 10, 2022

Walking into Erin Washington’s “I Think We’re Alone Now” exhibit at the Cleve Carney Museum of Art (CCMA), fluorescent colors pop everywhere, from the small sculptures on a platform on the floor to the drawings on the wall. Mixed into the drawings are lines of non-photo blue, visible to the viewer but invisible to some technologies.

In this collection of art, Washington, a fine artist and lecturer at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, was drawn to things that are both true and untrue depending on the context. She found meaning in the title of the song “I Think We’re Alone Now,” first released by Tommy James and The Shondells in 1967, and how it encapsulated the experience of isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic that was at once universal and lonely. The intentions behind many of the pieces in the collection share this ambiguity.

At the exhibit, viewers can enter a domed structure made with space blankets. These thin, lightweight sheets resemble aluminum foil and are opaque on the outside of the structure but semi-transparent on the inside.

“The idea is that when you’re walking inside of this, not only do you become surrounded by the space, but you have this weird, magical glimpse of the outside world,” Washington explained. “You’re existing in this room with other people, but they might not know that they’re existing with you.”

Another key piece in the exhibit is a laptop keyboard sculpture Washington created out of materials including plaster bandages and cardboard. As a child, Washington was fascinated by the computers available at school. She did her best to replicate them at home using paper and cardboard, even creating pretend floppy disks and drives to put them in.

“After creating these things, I would sit in my bedroom and just do this,” she said, playfully mimicking typing.

Washington was reminded of this childhood experience as she taught classes in isolation.

“I felt like I was that kid on the cardboard computer, talking to a room of black squares,” she said.

The keyboard is displayed alongside multiple tea kettle sculptures. The kettles are inspired by four she destroyed by leaving them unattended. On the same platform is a green witch-like hand based on hands she’d create then sneak on camera during online classes, trying to gain a reaction from her students.

The exhibit also features a grid of 15 automatic drawings. Washington was at home streaming television, operas and ballets when she found she needed something to do with her hands. She created the first layers of these drawings while focusing her eyes elsewhere.

“You’re simply reacting rather than processing while you’re making. A lot of times analyzing while you’re making can be detrimental to discovery and play,” Washington said about automatic drawing.

Although those were drawn intuitively, many of Washington’s pieces incorporate layers of research. Justin Witte, the curator/director of the museum, has 21 years of experience in fine arts. He pointed this out when asked what was unique about working with Washington.

“It’s distinct with her the amount of connections and research that circle around her work,” Witte said.

He described Washington’s art as a wonderful combination of academic and humorous. Among the pieces this is evident in is one that references Renaissance painter Giorgione’s “The Tempest” and one that references a defaced classical Greek sculpture of Aphrodite.

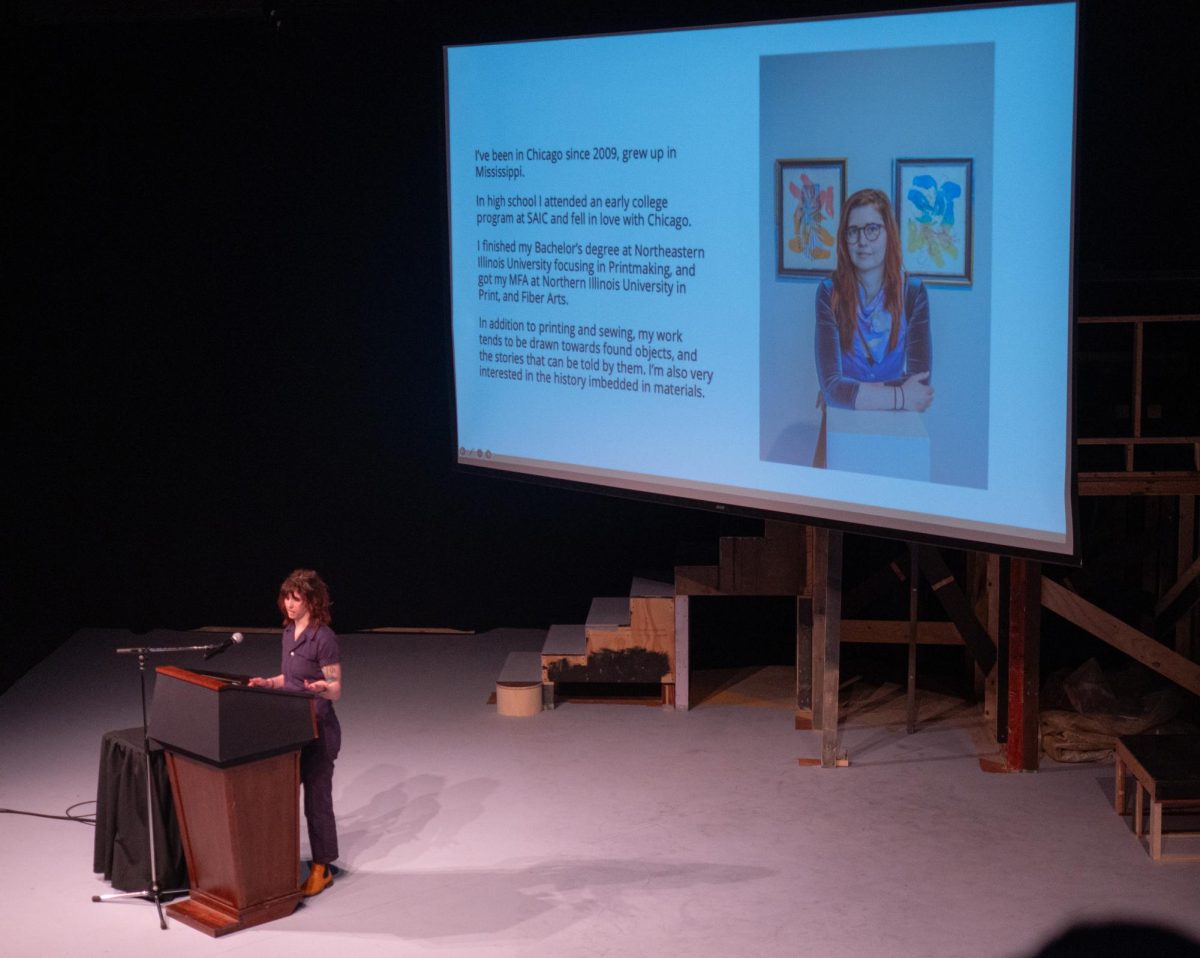

Collaborating with Washington, Witte was able to curate the presentation and information in the exhibit in a way that served the museum’s academic audience, who attended a reception on Sept. 15.

“We set up a wireless mic with Erin, and she walked through the show,” Witte said. “It was a great way for our students to hear directly from the artist about the work. And I find that a lot of people who come to our spaces like to have that background information given to them.”

Despite the thought behind it, Washington’s work doesn’t take itself too seriously.

“These are ambiguous feelings that a lot of us have, and this is permission to explore those in a completely safe way,” Washington said. “The painting’s not going to hurt you.”

On the back of one piece is a sign that reads “kick me.”

“No one’s going to kick the sculpture.” No one has yet, Washington clarified, laughing. “Everyone threatens to, but no one does. I won’t be mad if someone does.”

The sculpture also uses a pair of the artist’s own boots.

She told the story of when she took the boots off her feet and filled them with spray foam the first time the piece was installed. “My curator just turns to me and has this look of concern on his face and is like, ‘Your train to get back to Chicago is leaving in 30 minutes. Do you have shoes?’”

She did, in fact, have another pair of shoes with her.

“Yes, there is a thinking mechanism behind all of this,” she said. “But it’s completely absurd.”

“It still has that playful aspect to it,” Witte said, addressing Washington’s work as a whole.

Washington doesn’t have a favorite piece in the exhibit. She isn’t a parent, she clarified, but that would feel to her like choosing a favorite child.

“I Think We’re Alone Now” will be at the CCMA until Nov. 20 and can be visited for free. More information is available at the CCMA’s website.