COD professor leads team to predict tornadoes two to three weeks ahead

April 20, 2016

College of DuPage professor Victor Gensini has invented a new method for predicting tornadoes two to three weeks in advance. His team currently includes COD professor Paul Sirvatka, Brad Barrett of the U.S. Naval Academy, John Allen of Columbia University, private sector weather forecaster David Gold and Northern Illinois University meteorology professor Al Mariano. The team is growing by the week, and the COD-spearheaded research has taught the global meteorology community much more about how tornados form.

Tornados are one of the most destructive and chaotic severe weather systems that face the United States. They have taken countless lives over the past century of recorded data. Here in Illinois, there are on average 35 tornadoes each year, as reported by the Chicago Tribune. Notable twisters include the 1990 Maywood tornado took 29 lives and injured 350 people, and the more recent 2015 Fairdale and Rochelle northern Illinois tornado destroyed small towns and occurred about 10 miles south of a nuclear power plant. It’s important to be able to detect them early to prepare for worst case scenario.

Gensini and his team found a correlation between an atmospheric fingerprint left behind from storms and similar weather conditions that occurred in many past severe storms that harbored tornados.

“You really go back in time and look at major historical events,” said Gensini. “Around here, an event that everyone remembers is the Plainfield tornado in 1990, but we’ve had other big events. Last year, the Fairdale-Rochelle tornado hit out to our west through DeKalb. Each one of these big severe weather events leaves behind an atmospheric fingerprint, and we go back three weeks from that event. We look at features that are analogous weather conditions that you could identify in other events.”

These fingerprints are found in the atmosphere in the form of jet streams, which are narrow bands of wind about 30,000 to 70,000 feet up in the atmosphere. “Prior to the events, we’re finding these features in the atmosphere, and two to three weeks later there were these severe weather events,” Gensini continued. “We’re going up and looking at the jet stream, which is up where commercial aircraft fly at about 30,000 to 35,000 feet, and we look for wind patterns up there that could maybe give us an idea that these events are going to happen.”

Jet streams follow the boundaries between hot and cold conditions and normally run west to east. They are described by the National Weather Service as “rivers of air,” and help meteorologists predict cold and warm fronts, as well as wind patterns.

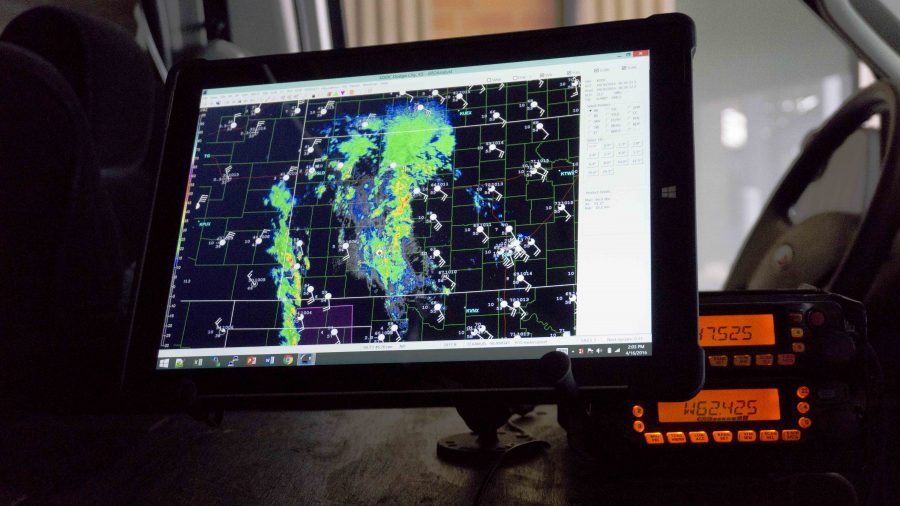

Gensini utilized the information gathered by weather balloons that float up to the jet stream to help create his theory. Weather balloons float up to the jet stream, record data and pop as the pressure outside the balloon decreases and forces the helium-filled balloon to expand. The data is streamed to a computer where it is analyzed.

Although this is a major breakthrough in meteorology and weather prediction, Gensini believes this will not change the average person’s life. Due to how our weather services predict and release information for severe weather, he believes that knowing a tornado could possibly come two to three weeks in advance will not help the majority of people.

This research will not alter the way you receive tornado watches and warnings. Those are all broadcasted to you through your TV screens and radio on the day the storm occurs. This will mostly affect people who are in charge of emergency planning and insurance companies, who have to prepare for disaster and mediate recovery if a severe storm causes destruction.

“This is primarily going to influence insurance companies, emergency managers, school administrators, and people that need to move assets out of the way from potential harm and need a long lead time to do it,” said Gensini. ‘For instance, an insurance company that has thousands of clients in Kansas; if they’re expecting a big tornado outbreak, they may purchase a catastrophe bond to help mitigate against the number of claims that they might experience. It’s a field called reinsurance. Reinsurance is basically insurance for insurance companies.”

Although this will help reinsurance and insurance companies alike, the research still has to grow and continue to condense the area of observation. So far, the system has been able to predict tornadoes to occur in large areas of the United States. Gensini believes that with more funding and time the team will be able to condense the prediction area significantly.

“So what we do is we’re saying east of the Rocky Mountains in the United States there’s either going to be above average, below average or normal average activity,” said Gensini. “That far out it is very difficult to predict, so you need a very big area. In the future, as we continue the research and continue to scale we want to be able to, instead of being the United States, want to be able to say the Midwest, the Southeast, the Northeast and break it down into regions.”

“That’s the next piece of the research,” continued Gensini. “We’ve got a lot more work to do. Hopefully research money and people buying into our ideas will help fund us. That’s our biggest obstacle, time and money. We’re hoping we can do it. Maybe in the next five years we can have a forecast three weeks out for a four or five state area. That would be sort of a best case scenario.”