At top colleges that train America’s elite, veterans are an almost invisible minority

Princeton sophomore and Marines veteran Sam Fendlar at the Ivy League Veterans Council. 9/29/18 Photo by John O’Boyle

November 27, 2018

PRINCETON, N.J. — The ink starts at Sam Fendler’s left wrist and winds up his arm, a tableau of his life before college that begins with a block of text: “People sleep peaceably in their beds at night only because rough men stand ready to do violence on their behalf.” At the top of the tattoo, above a version of the Marine Corps emblem, an American flag wraps around his shoulder.

Fendler figures he might be the only student at Princeton University with a full sleeve tattoo. He’s also among the school’s very few veterans.

In his two years at Penn State before transferring to Princeton this fall, he rarely mentioned his military service. But he’s been more open about it at Princeton, which has 12 veterans, up from just one three years ago. In his sociology class, the Western Way of War, he felt it might add to the conversation.

“I don’t like to lead with this about myself,” he said during a discussion group on Thucydides’ history of the Peloponnesian War, “but I’m a veteran and I’ve been to war.”

Many state universities and community colleges have large veteran populations and robust programs to recruit veterans and help them adjust to college life. But at the nation’s most selective schools, where most students follow the traditional pipeline from high school to a degree within four years — and from which many go on to leadership roles in government and industry — veterans like Fendler are an anomaly.

Though America’s top institutions are trying to increase this population, who bring with them not only a unique perspective on the world but also, collectively, millions of dollars in taxpayer-funded GI Bill benefits, veterans still make up well under 1 percent of the undergraduates on most of these campuses. That’s out of about a million veterans and their family members enrolled in higher education under the GI Bill, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs.

For years the military didn’t promote these most selective schools as an option and veterans didn’t think they could get in. Many of the colleges, meanwhile, didn’t know how to handle their applications and hadn’t thought about why they should even want veterans.

Veterans advocates argue that those who volunteered to serve in the military should have the chance to attend the nation’s best schools if they qualify, and that their presence boosts diversity and adds to the richness of campus life.

Community college writing professor Wick Sloane sees a more fundamental reason that people should care whether veterans attend schools that educate the nation’s elite.

“A disproportionate number of the public leaders who send other people’s children to war went to [elite] schools,” said Sloane, who authors an annual survey of veteran enrollment at top schools. “Maybe, just maybe, if [those] students were sitting in English and history class with men and women whom the U.S. had sent to war, those students, as government leaders later in life, would think harder before sending other people’s children off to war.”

This year Sloane tallied 844 veterans across 36 of the nation’s most select colleges and universities. Columbia University, which first welcomed veterans in large numbers after World War II, accounts for more than half of that total, with 443 veterans enrolled in 2018, though most are in its School of General Studies set up for older-than-traditional-age students and separate from the general enrollment.

Many elite institutions educate plenty of future veterans — students in officer-training programs who will receive military commission when they graduate. And veterans are well-represented in the graduate programs at many elite schools, advocates said, but many served as officers and attended service academies or already had four-year degrees before joining the military.

Most enlisted veterans, on the other hand, have been out of an academic setting for years and many didn’t have the grades, test scores or desire to apply to a top university when they were in high school.

Brown University student Aimee Chartier, a Marine veteran, attends the Ivy League Veterans Council. 9/29/18 Photo by John O’Boyle

“I was an awful student,” said Aimee Chartier, now a sophomore political science major at Brown University. “I didn’t think I’d go to college at all, let alone the Ivy League.”

Growing up in Providence, Rhode Island, she knew Brown as the college up on the hill, forever away and out of reach. She dropped out of high school for a while, and joined the Marines at 19. She served five years as an intelligence analyst, then started classes at the Community College of Rhode Island. She carried a 4.0 grade-point average, but laughed when her German professor suggested she apply to Brown.

In 2017, however, Brown began to waive application fees for veterans and guarantee phone interviews, so she and her husband, who also served in the Marines, applied. Both were accepted, and started as freshmen in the fall of 2017, with all four years covered by scholarships. The school now has 17 undergraduate veterans; three are women, according to Chartier.

Smith College student Jessica Nelson attends the Ivy League Veterans Council. 9/29/18 Photo by John O’Boyle

“A lot of people have never met a veteran,” said Jessica Nelson, one of two veterans at all-woman Smith College, where she is a senior. As a black woman who grew up in the South, she initially felt like an outsider in Northampton, Massachusetts. Her military service made her even more of an anomaly, and her classmates were curious to know more. “They want to know how it is to deal with a hyper-conservative, hyper-masculine environment.”

Nelson, who is 30, started college at Texas A&M in the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, but left after a few semesters and enlisted in the Marine Corps. She served five years as a topographical analyst attached to an infantry battalion, which had 10 women among the hundreds of Marines. Until this year she was still in the Marine Reserves, which required a weekend of service each month with an infantry unit near Smith. She bounced back and forth between the two worlds, sometimes feeling out of place in both. “It can be a little bit alienating,” she said.

Chartier and Nelson were on Princeton’s campus this September for the biannual meeting of the Ivy League Veterans Council. A social gathering and an exchange of ideas, the meetings also have another purpose: to push the host schools to more deeply consider their veteran policies, Adam Behrendt, a Stanford senior and the council’s president, said.

At the council’s spring meeting last year, Cornell Provost Michael Kotlikoff announced an ambitious goal of enrolling 100 undergraduate veterans at Cornell within three years. The school has 41 now, according to school administrators — up from none three years ago.

This recent push for more veterans at some of America’s elite schools can be traced to James Wright, a former Marine who served as president of Dartmouth from 1998 to 2009. The son of a bartender who fought in World War II, Wright joined the Marines after high school, later earned a Ph.D. in history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and started teaching at Dartmouth in 1969.

As president, Wright said, he thought a lot about enriching and diversifying the student body, but he didn’t factor veterans into those calculations until 2005, when he visited Bethesda Naval Hospital and met with troops who had been wounded in Iraq. It was the first of 30 trips he made to military hospitals. Some of these veterans weren’t sure what to do with their lives now that their military careers had ended. He encouraged them to continue their educations, and started a counseling program to help them navigate the process of getting to and through college.

Wright’s peers at other elite schools commended his efforts to help veterans, but “I didn’t get a lot of people lining up and saying, ‘What can we do to join in and help out?’ ” he said. Wright answered the question for them. He helped craft the Yellow Ribbon Program, a component of the 2008 Post-9/11 GI Bill that expanded veterans’ access to expensive private colleges. The colleges agreed to help cover shortfalls between the maximum amount covered by the GI Bill and the total cost, with the VA matching the schools’ contributions.

This put funding in place, but that wasn’t enough. For several years the numbers of veterans barely climbed above a handful at many of the most selective colleges and universities.

Sloane discovered this by accident. He teaches writing at Bunker Hill Community College in Boston and in the mid-2000s started seeing more students there who had served in Iraq and Afghanistan. “Veterans were writing these searing stories about what they had been through,” Sloane said. He wasn’t sure how to work with students processing such exceptional experiences. He couldn’t find much in academic literature about teaching writing to veterans, so he called the two elite schools he had attended, Williams and Yale, for advice. He wasn’t expecting their response: “Why are you asking us? We don’t have any veterans.”

Sloane figured Williams and Yale must be the exception, so he called more top colleges.

“Year after year, almost none have the number [of veterans enrolled] before I call. That means to me that no one, starting with the college president, wants the number,” said Sloane, who uses his survey as a public reminder to elite institutions that they don’t have enough veterans. “In leadership and life, symbolism counts. Intentional or not, the low numbers of veterans signals to all of higher ed that these students do not matter.”

Now more schools appear to be trying to show that veterans do matter to them, but boosting their numbers hasn’t been easy. With application criteria often based on test scores, grade-point averages and extracurricular activities, admissions officers often don’t know how to account for military experience. They have had to familiarize themselves with military culture, whether in reading a recommendation letter from a commanding officer or deciphering the DD 214 — the military discharge papers that document a veteran’s training, deployments and awards.

Several programs started over the last half-dozen years help bridge the gap between qualified veterans and top-tier colleges.

Service to School works with admissions officers to help them better understand veterans and how their military experiences might translate to academic success. “Someone who served on a submarine went to a very intense, high-attrition, academically serious school and has proven their chops at being able to do advanced math and science in the military,” Andrea Goldstein, the chief executive officer, said. “But saying someone was just a submariner isn’t going to tell that story.”

The group works with about 1,700 veterans a year, 60 percent of them the first in their families to go to college. Each is paired with a volunteer who helps him or her select schools, hone applications and identify weak spots that can be strengthened with coursework before applying. “They’ve never had a network of people mentoring them, saying ‘You can go to a highly selective school,’ ” Goldstein said.

At the Warrior-Scholar Project, enlisted veterans attend one- and two-week academic boot camps on several top-tier campuses across the country that prepare them for rigorous college coursework.

The Posse Veterans Program, which now has veterans at Wesleyan University, Vassar College, the University of Virginia and Dartmouth, uses a cohort model. Veterans enter the schools in groups of 10, and meet weekly with each other and individually with faculty advisors. While many have already taken college courses, Posse students agree to forego any previous college credits and start as freshmen so as to get the full undergraduate experience.

This can be a disincentive for veterans who already have a year or two of credits. Veterans not in the Posse program can face similar dilemmas, depending on a school’s transfer policies and willingness to accept prior credits. The extra time can also create a financial pinch if the veteran has already tapped into GI Bill benefits, which cover only up to four years.

Colleges vary widely in how they fund veterans. Some require that veterans use their GI Bill money first, with grants and scholarships put toward the remainder. Others don’t factor those benefits into their calculations. Fendler, for instance, goes to Princeton for free, with the school paying for tuition, room and board; he plans to put his GI Bill benefits toward law school.

But until recently, the school’s generous aid package didn’t matter. Princeton stopped its transfer program in 1990, and didn’t allow students to apply who had taken any college courses after high school. Many other top schools have similarly restrictive or limited transfer programs. “That was a huge penalty to military veterans,” said Elizabeth Colagiuri, the deputy dean at Princeton and a Navy veteran.

Princeton rescinded the prior-college restriction last year and admitted five veterans as freshmen, and this year reinstated its transfer program.

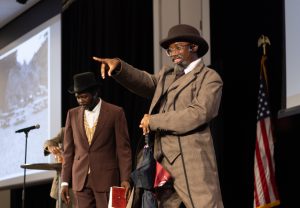

Princeton sophomore Kenneth Oku, a veteran of the Army, at the Ivy League Veterans Council. 9/29/18 Photo by John O’Boyle

Kenneth Oku arrived this fall as a sophomore, one of six veteran transfers. At 33, he is far older than his classmates, but with a boyish face, blue plaid shirt, khakis and backpack slung over his shoulder, he blended in with his peers as he hustled across campus for a computer science class.

“I always knew I could do it if I got the chance,” he said. “I just didn’t think I’d ever get the chance.”

Many of Oku’s high school classmates in Superior, Wisconsin, did not graduate, and few went to college. He joined the Army, trained as an infantryman and deployed twice to Iraq. He also attended the Army’s Ranger School, a physically and mentally grueling program designed to weed out the weak. “Their job is to make sure only certain people make it through,” he said. As for his Ivy League education, Oku said, “I’m ready for this, whatever they bring on. I’m trained for this.”

Oku, who was also accepted at Stanford and MIT, knew he’d be getting a good education at Princeton. But spending time with other new students at a several-day orientation had an unexpected effect — unpacking wartime experiences that he had tucked away years ago.

“Everybody else opened up, so I opened up,” he said. “I probably told them more than I’ve told a lot of other people, things I’ve never said before.”

And this gave his fellow students a perspective they may have never heard before.

This story on veteran students was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for our higher education newsletter.

The post At top colleges that train America’s elite, veterans are an almost invisible minority appeared first on The Hechinger Report.