After Janus, the National Education Association takes stock of its movement

July 5, 2018

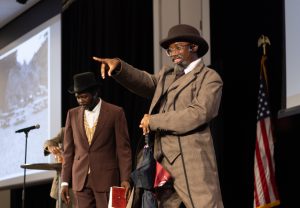

THE ANNUAL MEETING of the National Education Association, the country’s largest public-sector union, held in Minnesota this week was much more high stakes than in years past. Typically, the convention is a chance for educators to vote on bread-and-butter issues like budget priorities and advocacy target areas. But the 8,000 or so students, retired teachers, and NEA delegates who descended on the Minneapolis Convention Center had more existential questions on their minds. In the wake of a U.S Supreme Court ruling that dealt a crippling blow to public-sector unions, they debated strategies to expand their membership, keep union members apprised of their rights, and recover from the impending financial loss that is sure to happen in a post-Janus world.

In Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, a 5-4 Supreme Court majority ruled last week that despite laws requiring public-sector unions to represent all workers in a workplace, fees charged to non-members to support the costs of collective bargaining violate the First Amendment. For more than four decades, the Court has held it constitutional for unions to collect money from non-members to support the costs of negotiating contracts on their behalf. Janus overturned that precedent, meaning that employees can now enjoy the benefits of collective bargaining without having to pay for it. Labor unions are bracing for substantial revenue loss.

Now, the choice before teachers is paying either hundreds of dollars in annual membership dues, or nothing at all. The NEA, which represents a little over 3 million members, is forecasting a loss of 370,000 members over the next two years. Approximately 88,000 educators have been non-members paying NEA agency fees, and the union anticipates at least several hundred thousand current members will also rescind their union cards.