A progression of villagers, dressed in the same red robes, slowly walk over a bridge and into an awning. They all don identical masks, and all carry a lit torch. They arrive to sit at a noh play, an example of traditional Japanese theater. Among the audience sits Yuu, then a boy, gaping at a masked man on stage making his way toward a lookout to the hum of the narrators and their drums. Meanwhile, a house in the village burns with a man inside.

So opens “Village,” a newly-released Netflix movie that takes place in Kamon village. Minute and among a procession of mountains, Kamon isn’t a place to visit. More to the point, it’s the home of a recently installed waste management facility. Eerily, from a distance, it doesn’t even look like it exists and was instead pasted onto the landscape.

Skipping forward, Yuu, now an adult, works at the facility, day-in and day-out, to pay off his mother’s gambling debts. She gave into her vices when Yuu’s father passed, a man we have yet to hear much at all about. It’s at a random point in the dreary, outcast life of Yuu that Misaki, a young woman looking for a job, moves to the village to become Mayor Ohashi’s assistant. Toru, Yuu’s coworker, tormentor, and son of Mayor Ohashi, has eyes for Misaki. To his dismay, though, Misaki has a liking for Yuu.

The strong suit of “Village” is in its themes and symbolism. Before we’re shown any bit of the story itself, a quote is displayed from an old Japanese play, Kanton: Waking up after 50 glorious years, it was all merely a dream. Truly, everything is but an empty dream. It’s from this point that the audience is taken on a journey. First, we see Yuu as a loner, an outsider ostracized by the village for a grievance unbeknown to us. He’s angry, pitiful, and has no life but his work. But, once Misaki enters Yuu’s life in the form of an old friend and a partner, everything changes.

In one scene, Misaki helps Yuu confront his feelings of anger and frustration, because of how he’s been treated. That is, despite him not being responsible for why the villagers look down on him. He cries and whimpers into Misaki’s arms and, in the next moment, they kiss and end up sleeping together. After a brief fade out and fade in, we see Yuu as a clean-shaven, confident man lecturing a field trip of children about the waste management facility.

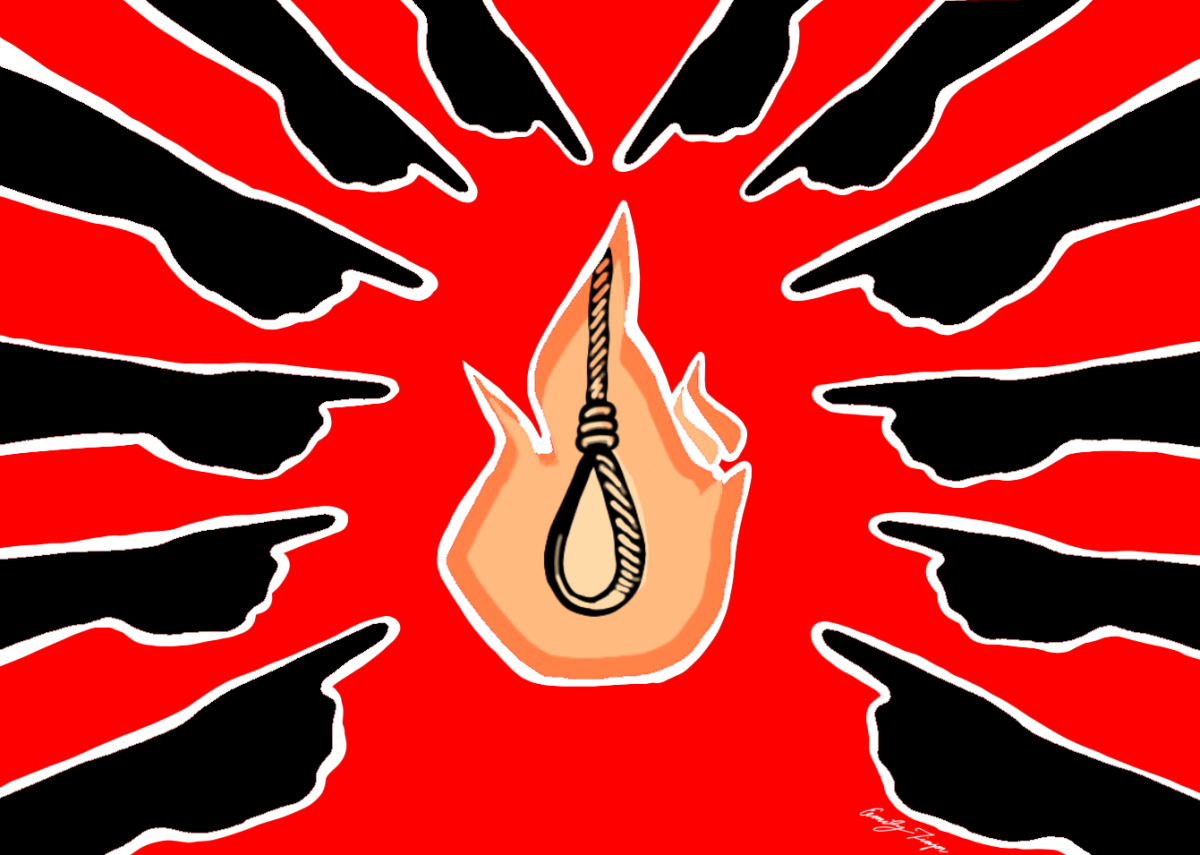

In the rapid reversal of fortunes, Toru becomes jealous, so much so that he’s driven to assault Misaki and, in turn, Yuu. But the dream-like quality of Yuu’s new life comes at the cost of hiding the truth. Misaki reveals that in the play Kanton, the protagonist slept for all those years just to wake up to the life he had been living before his dream as emperor. Likewise, while living his best life, Mayor Ohashi continues to hide the toxic garbage disposal that he’s been doing in the dump that comes to bite both of them.

How these ideas unfold in “Village” is beautiful, but there were times when it felt drab. One such example is the subpar acting from Wataru Ichinose as Toru came to light in scenes where his subtlety was confounded by Rusei Yokohama’s overacting as Yuu. The key example of this to me was the scene where Toru sneaks into Misaki’s home and attempts to convince her of Yuu’s unlikability. In the first half of it, Toru awkwardly speaks to Misaki after making his entrance and shows her a video of Yuu, with a work crew, illegally disposing of toxic waste.

“Well? This is a crime, you know. What’s so good about him?”

“Did you make him do this?” Misaki questions.

“Come on. Don’t pin the blame on me.”

Misaki is clearly aware of Toru’s culpability as the one behind the toxic waste dump.

Such an idea also spoke to how flat the characters were, where Toru was showing Misaki a video of Yuu disposing of the toxic material in the dump, committing a crime, as though she wouldn’t at that point have known that Yuu was doing so to pay for his mother’s excessive gambling losses.

But such is the nature of “Village’s” themes, that of the ugliness of modern times, i.e. Toru’s behavior being projected onto an isolated village. Mayor Ohashi’s wife, a woman who appears to be taken from ancient Japan and relocated to the modern one, represents the disintegration of morality. She looks down on all that’s happening around her with haplessness from her age.

That, among other examples of modern realities invading the community’s quiet domesticity, is enough reason to see “Village.” 4/5